A Signal of Hope

Climate groups tackle Big Oil in Signal Hill

By Mallika Seshadri, Jarrett Carpenter, Isaac Vargas and Enzo Luna

A young Madison Alvara often meandered through her local woods. The dense foliage and creek trickling through made her feel safe.

Years rolled on. And as a New Year’s Resolution on January 1, 2023, she and her wife, Stephanie, vowed to do something — practically anything — to care for the environment that nurtured her as a child. They created a group called Climate Brunch, which soon became the driving force behind a movement to upend the Signal Hill Petroleum Company, whose roots have been long entangled with the city of Signal Hill.

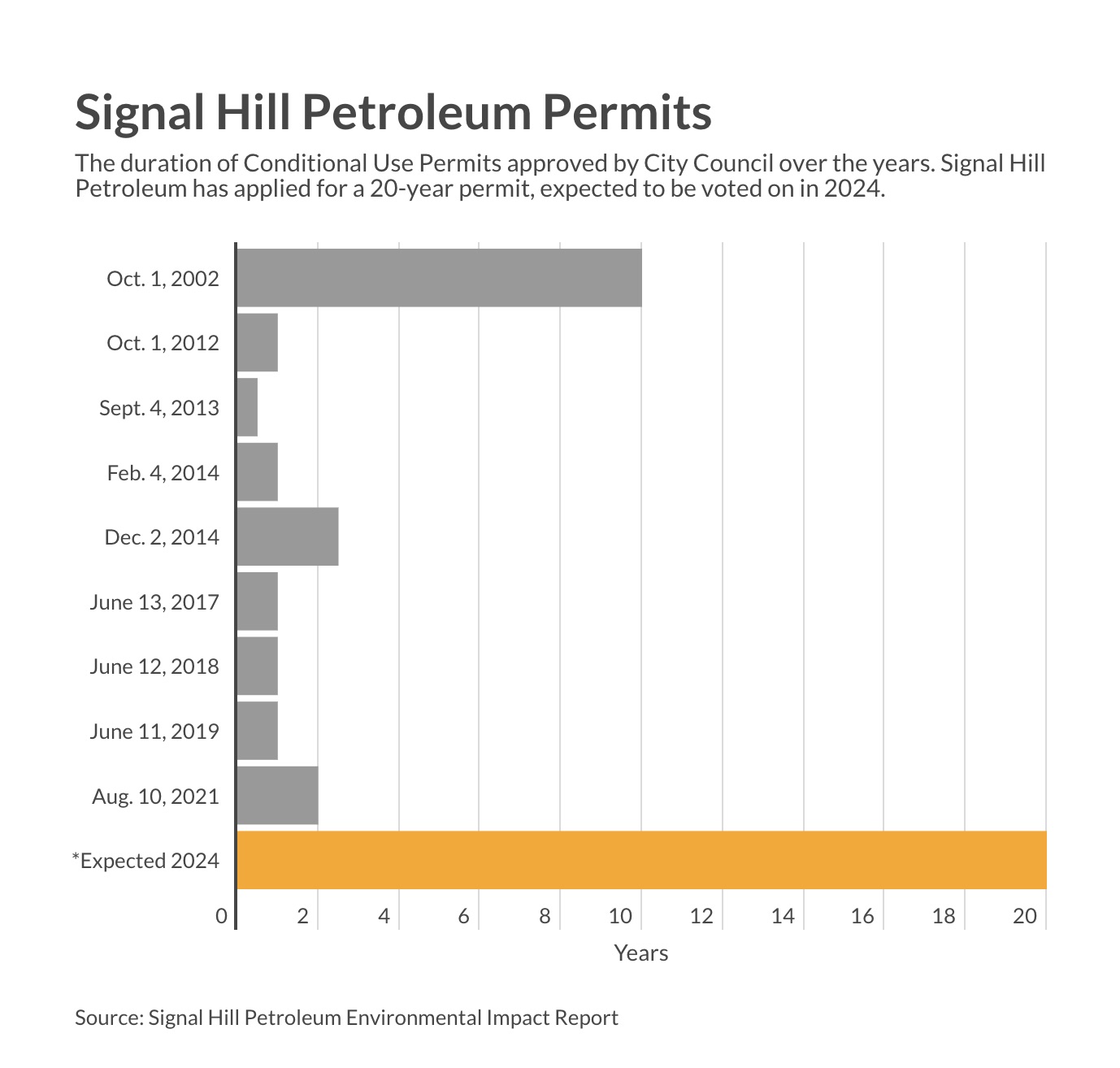

For more than a year, Climate Brunch has targeted a permit that would extend the oil company’s operations for 20 years and add 46 new rigs — a move they believe violates a state law prohibiting the construction of new wells.

Climate Brunch is just one of many organizations taking on Big Oil in Los Angeles. Organizations including STAND-L.A. and Sierra Club have successfully driven out large companies like Chevron and AllenCo.

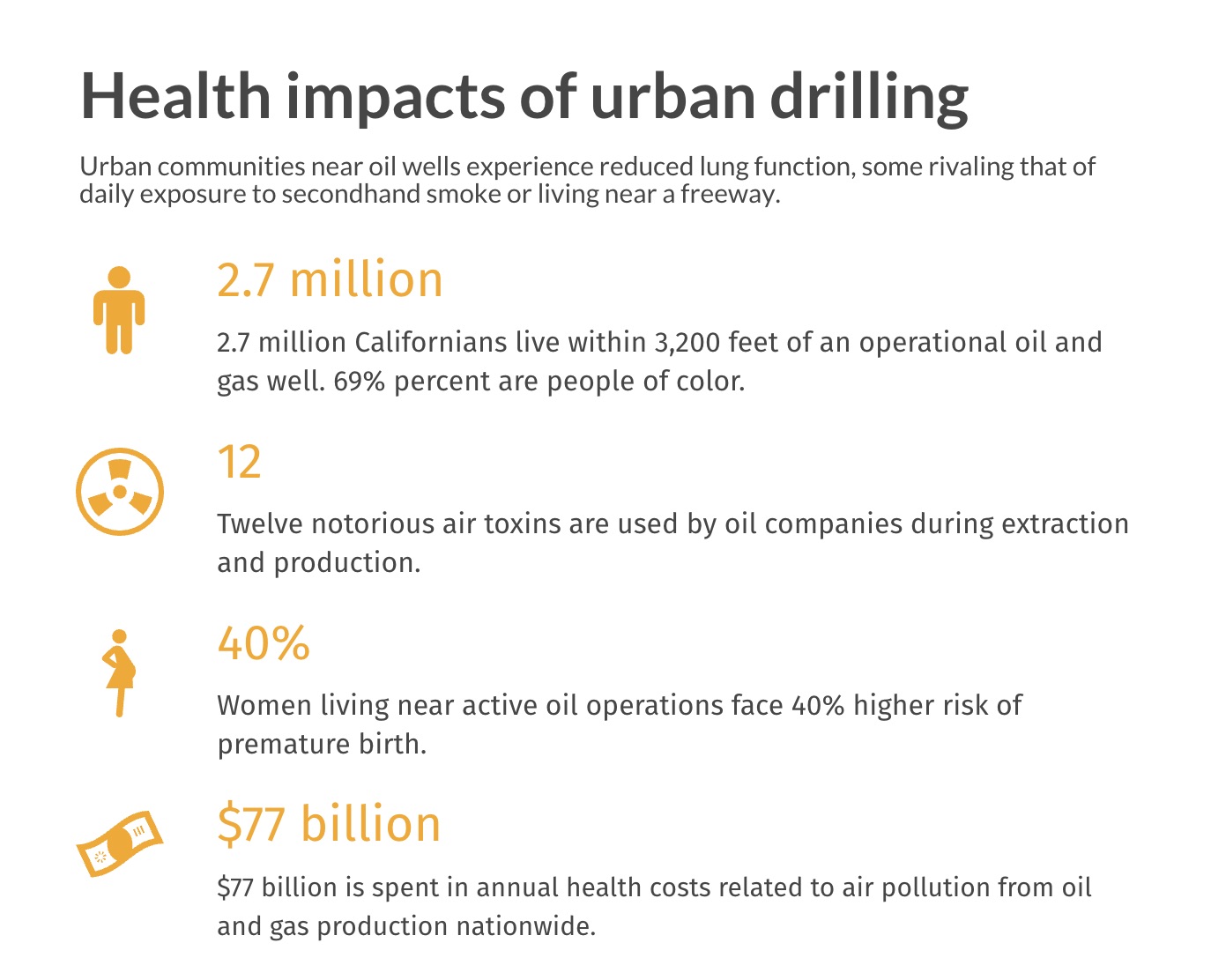

A lot of the remaining drill sites are located near communities of color, leading to disproportionate increases in adverse health effects among Black and Latino residents.

“We looked at both lung strength and size,” said Jill Johnston, a public health professor at USC’s Keck School of Medicine. “Essentially, we saw that people living closer to the well sites experience lung deficits similar to those of living with a smoker.”

Madison and Stephanie Alvara stand on a basketball court in Signal Hill, CA's Discovery Well Park, while an oil drill operates behind. July 7, 2024.

A New Year's Resolution That Stuck

Climate Brunch began as a New Year’s resolution – one of the few that actually stuck.

Madison Alvara and her wife Stephanie, who had married and moved to Pasadena, decided to gather a group of friends for a monthly potluck devoted to fulfilling prescribed actions recommended by climate change makers.

They also started combing through a California Environmental Quality Act portal, which lists projects going on throughout the state, and chanced upon the permit being considered by Signal Hill’s city council.

The group — now comprised of up to 20 active members — got to work, mailing postcards to roughly 40% of the city and knocking on doors. If someone didn’t answer, the group would place a flier at their doorstep.

Climate Brunch urged locals to turn up for public hearings and speak out against the permit. Their efforts alone took public comment from being a four-person activity, involving Madison Alvara and two pro-oil speakers, to a roaring room of more than 50 activists.

“Every single public comment [at the most recent hearing] was against the permit and folks we'd never seen before,” Madison Alvara said. “That was really moving, like it really actually made me cry.”

Climate Brunch also broadened their reach to alert and involve larger climate organizations, added Stephanie Alvara, an environmental engineer by profession.

They have since collaborated with Sierra Club, Food & Water Watch, and the Center for Biological Diversity — handing out flyers at their events and getting their help with establishing petitions.

The Sierra Club’s petition for their cause has gathered 740 signatures so far — with only 74 to go until they have met their goal.

“If you've ever played Mario Kart, where you hit that bar that zooms you faster, that's how it felt,” Stephanie Alvara said. “Their resources and experience with organizing just elevated us to another level.”

Stephanie Alvara emphasized that even at the most local level, everything helps.

“You have power: don't think that you don't — just like every ant and every bee within their colony has a role, and without them, the colony wouldn't function, you also have a role. And we could do this together.”

Going up against ‘Porcupine Hill’

The city of Signal Hill’s founding fathers decided to cut themselves out of Long Beach in 1924 — creating a 2.2 square mile “island” where they wouldn’t be touched by Long Beach's per-barrel oil tax and could build up a “Porcupine Hill” spiked with wells everywhere.

The city has never been shy about its historic connections to oil; and, a century after its founding, Signal Hill City Manager Carlo Tomaino confirmed that is still the case today — as children climb up and slide down beehive inspired jungle gyms at the local Signal Hill and Discovery Well parks, each revered for its views of the greater Long Beach area, with the ocean just over three miles away and thousands of active oil derricks pumping even closer.

The Signal Hill Petroleum Company currently operates 62 wells across seven different drill sites. They also own 95% of the Long Beach Oil Field, which is home to 1,550 wells — and see themselves as being an integral part of the community.

“One of the things that we really pride ourselves on is being a good neighbor and giving back,” said David Slater, Signal Hill Petroleum’s executive vice president and chief operating officer, in a video posted to the company’s Facebook page on May 10.

Since Signal Hill Petroleum’s founding three decades ago, Slater said the company has developed 550 single-family homes and contributed 660,000 square feet of retail space and almost 2 million square feet of warehouse space.

The company’s website also touts its sponsorship of this summer’s “Movies in the Park” series — alongside Long Beach Partners of Parks, the city of Long Beach and Long Beach Parks, Recreation and Marine.

They also sponsored the City of Signal Hill and Signal Hill Community Foundation’s Concerts in the Park Series, made trips to elementary schools’ career days and sponsored Cal State Long Beach’s Math and Science Department, along with the Ukleja Center for Ethical Leadership.

Climate Brunch, however, has been sounding alarms on the company’s close ties with the city — especially Big Oil’s stake in local politics.

In April, the Signal Hill Petroleum Company was the “platinum sponsor” for the city’s 100th anniversary and gave the city a $100,000 donation.

Meanwhile, employees of the oil company have taken on leadership roles in the Signal Hill Chamber of Commerce, including Signal Hill Petroleum’s communications specialist, Holly Youpa, who was appointed as secretary in 2023.

The terms of Signal Hill’s mayor Lori Woods and vice mayor Edward Wilson, along with city councilmember Robert Copeland, expire this December. Each of their seats will be up for grabs in November. Their — and the other councilmembers — campaigns to get elected in the first place were backed by the Signal Hill Petroleum Company.

According to an analysis of campaign records from the City of Signal Hill’s City Clerk’s office, the Signal Hill Petroleum company has made campaign contributions totaling more than $8,000 to current city councilmembers’ collective campaigns dating back to 2011.

Not a single member of the city council was elected without the company’s support. Signal Hill Petroleum officials — including Slater, Craig Barto, Debra Montalvo Layton and Kevin Laney — also pitched in with more than $4,000 to support the campaigns of city councilmembers Tina Hansen and Keir Jones.

In an email to USC Annenberg, Woods said that the bulk of donations to her campaign came from local residents and businesses — and emphasized that the City Council adopted a limit on campaign contributions.

For this November’s election, she said candidates will not be able to receive a donation higher than $700.

This group of elected officials is on the verge of moving forward with a permit that would expand the operations of Signal Hill Petroleum for the next two decades — a move that some warn could be illegal and violate a California law signed in September, 2022.

“As an elected official, I have a duty to approach each issue with a comprehensive understanding, considering all facts and perspectives,” Woods said in an email. “My role as an elected representative obligates me to evaluate the facts presented, weigh the benefits and risks, consider potential positives and negatives, and respect the legal due process rights of our applicants.”

Children play in jungle gyms, and adults team up for a game of pickleball at Discovery Well Park in Signal Hill, CA. July 2024.

Rod Shapiro and friends play pickleball at Discovery Well park every Sunday morning.

It’s a hot day, and after a few minutes on the court, Shapiro is breathing heavily. About fifty feet behind him, an active oil well pumps invisible carbon monoxide gas, nitric oxides and methane gas into the air.

Shapiro knows urban oil wells are associated with adverse health risks, but he doesn’t know to what extent, and he views their presence as inevitable.

Like Shapiro, residents of affected communities are often unaware of the health impacts of oil drilling.

Johnston, the USC professor, teamed up with community health workers to survey people living in the West Adams and University Park neighborhoods. The survey found that 45% of residents were unaware they lived near active oil drilling, and 63% did not know how to contact regulatory authorities to report hazards and strange odors.

Climate Brunch found the same trend during their canvassing efforts in Signal Hill.

“The residents that did open their doors and spoke with us were just shocked,” Stephanie Alvara said. “‘Oh, this is happening? What can I do?’.”

Communities located near oil extraction report more asthma, headaches, nosebleeds and respiratory problems. Exposure to toxic emissions can lead to reproductive health risks including preterm birth, birth defects and miscarriage.

This is especially concerning for local activists as all of Signal Hill Petroleum’s drill sites are less than half the state recommended distance from the nearest home.

“This is a blatant disregard for the health of children, seniors, workers, and families,” said Signal Hill’s State Senator, Lena Gonzalez (D-Long Beach), in an email to USC Annenberg, “particularly in our most vulnerable communities and sensitive places like schools, childcare centers, and hospitals.”

Facing community backlash, Signal Hill Petroleum commissioned an environmental impact report to look at the public health ramifications of their proposed 46 new wells.

“No significant and unavoidable adverse impacts were identified,” the report stated.

Petroleum extraction sites are predominantly located in communities of color. The Inglewood Oil Field is the largest urban oil field in the U.S. and people of color make up 73% of the surrounding area. The majority of Signal Hill is also comprised of minorities and 40% are Hispanic or Latino.

“I love living here,” said Signal Hill resident Mary Gonzales, who has been helping Climate Brunch with their efforts.

Her dog lounging on her lap with brand new allergies gazed up at her, exhausted: “I don't think I would want [my kids] to raise any children here or to live here long term.”

Fighting On Multiple Fronts

Signal Hill is only one fight in California’s much larger battle against drilling. Oil is woven into the tapestry of the Golden State.

“Oil was really one of the first economic booms and economic drivers here in Southern California,” Johnston said. “What resulted was this really close development of housing, schools and businesses next to where these oil operations are happening.”

Ever since, activists across California have fought to hold oil companies accountable.

STAND-L.A., an environmental justice coalition based in Los Angeles, successfully championed an ordinance that will phase out drilling citywide. Grassroots activists at Sierra Club, a Sacramento-based organization, pressured Governor Gavin Newsom to expand the buffer zone between wells and protected areas.

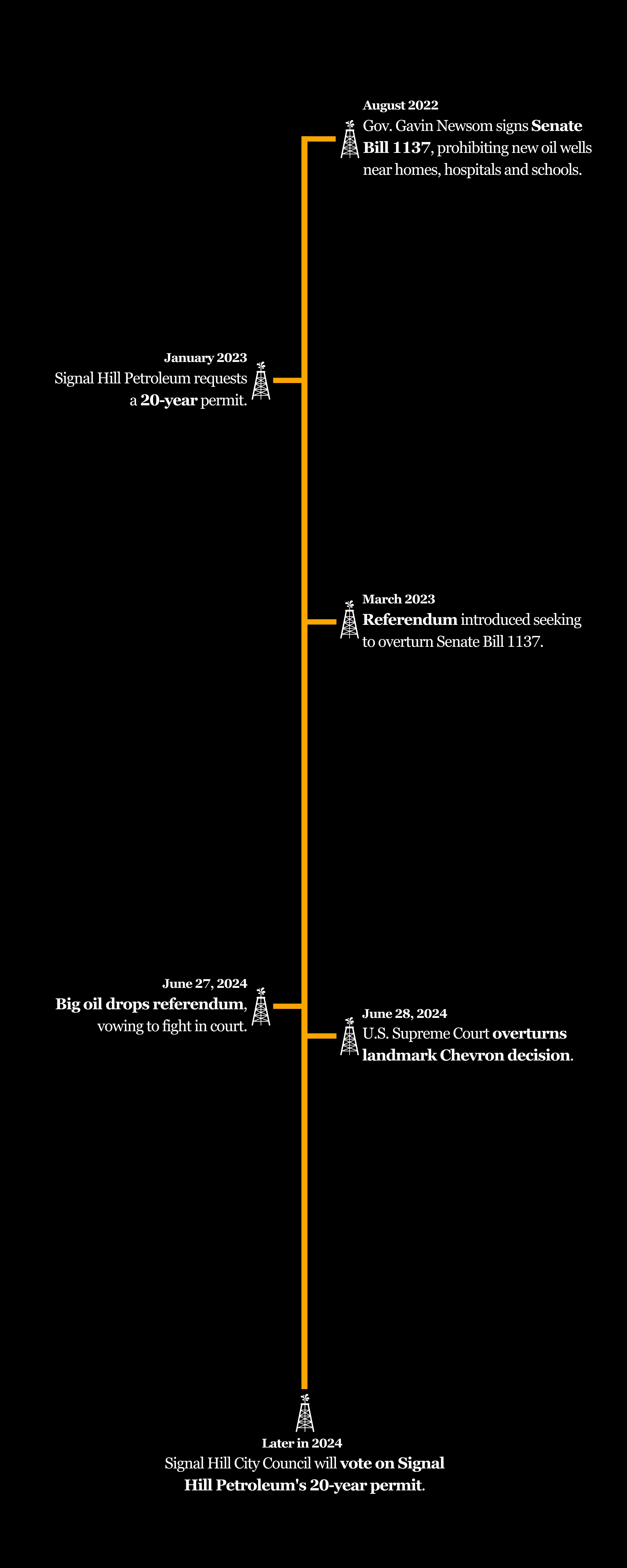

In August 2022, Newsom signed Senate Bill 1137 which prohibited the construction of new oil wells within 3,200 feet of homes, hospitals and schools. Oil companies challenged the law with a referendum, stalling the bill’s implementation.

The referendum was supposed to appear on the November 2024 ballot. But after Newsom enlisted the help of climate activists, celebrities and former governor Arnold Schwarzenegger to combat the measure, oil companies removed it from the ballot, and the law took effect on June 28, 2024.

Gonzalez, who authored the bill, emphasized that nobody is exempt.

“Senate Bill 1137 is in effect which means that any new or existing oil well will have to meet the requirements of the law,” she said in the email.

But climate activists know Big Oil won’t go down without a fight, and the U.S. Supreme Court’s reversal of the Chevron decision guarantees new challenges. The 1984 Chevron doctrine previously required judges to defer to federal agencies when interpreting ambiguous environmental laws. Now, oil companies can bypass scientific expertise and appeal directly to a judge.

Big Oil wasted no time pursuing this course of action. The same day the Chevron decision was being reconsidered, they dropped their November referendum and vowed to file litigation instead.

Madison and Stephanie Alvara acknowledge the battle against Big Oil can seem interminable, but they encourage others to celebrate incremental progress.

“Every time that oil derrick goes down right now, it's like, one more life [lost] potentially. It sounds dramatic, but every single amount of CO2 or methane that we're leaching into the air, it's kind of a slowly ticking time bomb,” Madison Alvara said. “...You could see that as terrifying, or you could see that as ‘Wow, if I'm able to even just prevent one extra ton from going into the air, I probably saved a life.’”

Jarrett contributed with writing, drone photography and reporting.

Enzo contributed with reporting, video, photography and coding the website.

Mallika contributed with writing and reporting. She also served as the group manager and produced the VoxPop.

Isaac contributed with reporting, visual storytelling and data visualizations.