In a Los Angeles backyard near the neighborhood of Mount Washington, Marvin Jordana steadily poises his metal tweezers over a buzzing glass jar. In it lies a single honey bee, laboring in its tiny movements.

“We only sting with bees that can’t really fly anymore. Eventually they’ll either get eaten or die from exposure,” says Marvin Jordana, a local beekeeper.

Jordana uses the tweezers to pluck the feeble insect up by the wings.

“I try to never pick them up by the abdomen. Can you imagine! A huge creature just picking you up like that?” he says.

Jennifer Power sits on a nearby tree stump for Jordana to prepare the bee.

“I get these little skin cancer patches,” says Power.

She stretches out her bare forearm and points. “So you see that red dot right there? You can go right for that.”

Jordana’s tweezers follow her direction. He uses the tweezers to hold the bug in place, while gently guiding and tapping it into position with his forefinger. In a moment, the bee stings Power, leaving its stinger injected in her skin. The bee stumbles toward the edge of her arm, until it reaches a final halt. Jordana catches the bee with his bare hands.

Jennifer Power receives bee venom therapy in Los Angeles, California. (Video by Rachel Hallett)

In a calming tone, Jodana coos to the bee.

“It’s okay. Thank you for doing this. We love you,” he whispers.

Jordana takes the bee's body to another section of the property and places it carefully in the grass; the insect’s final resting place.

“I honor the bees for that healing exchange. I know that they’re going to die after they sting me, but I take care of them too,” he says. “They are magnificent creatures; they’re saving lives.”

Bee venom therapy is an alternative treatment quickly gaining popularity among people suffering from chronic disease, like Lyme and Rheumatoid Arthritis. Stingers claim that bee venom therapy deeply improves or eradicates their symptoms. They find treatment and answers in nature, when traditional western medicine fails them.

And experts aren’t surprised.

They say that bee venom therapy is part of a larger evolution in alternative medicine; an inevitable product of the United States’ fractured healthcare system. A system so focused on human anatomy, yet completely void of personal connection.

“It's one of those things that keeps me up at night because our system is failing us.”

— Sarah Mojarad

“The future is a little bit grim because we see these hospital systems pushing physicians and other medical professionals to meet this patient quota,” says Sarah Mojarad, a lecturer at USC’s Viterbi School of Engineering and an expert in science misinformation.

“And when you only have 7 to 12 minutes with your physician, how much information can you actually provide to a patient?”

Chronic pain patients are most vulnerable to falling through the cracks of this system. They are the relentless stinging thorn in the healthcare system’s back; revealing the gaping failures of this parachute approach to medicine with each twist of their barb.

“It's one of those things that keeps me up at night,” says Mojarad.

“Because our system is failing us.”

A treatment that really stings

Jordana didn’t get into beekeeping for the honey, or the money. His interest grew out of an appreciation for the insect.

“I never liked the idea of getting bees from a package,” Jordana says.

Marvin Jordana's bees at his apiary in Los Angeles, California. (Video by Rachel Hallett)

Instead, Jordana’s first bees came from a seasoned beekeeper who saved the hive from a backyard extermination. This man’s hands were swollen and callused from years of practicing his craft. Instead of a proper protection veil, he wore only a paper bag with slitted eye holes: the mark of a true veteran beekeeper.

Jordana had no idea what he was in for.

“These were the most offensive feral bees I could have experienced as a beginner beekeeper. I was terrified,” Jordana says.

But for two years, Jordana sat with the bees every day.

“I found something so incredibly healing about just being near them,” he says.

Eventually, Jordana rescued more bees from neighboring areas. Every hive lives in its own box made up of wooden frames, for the bees to build their honeycomb. He lined them up at the base of a grassy hillside on his property. Each box is a different hive, or “beeing”, Jordana explains. Each hive has its own personality.

He points to the far right hive. “That’s my problem child.”

Jordana first stung himself by accident.

“I was wearing black yoga pants,” Jordana admits, “I was such a novice, I had no idea that black sets them off.”

One of his feral bees stung him on his right knee. But the following sensation surprised him.

“The chronic knee pain that had been bothering me left within minutes,” Jordana says.

Jordana was surprised by the incident, but thrilled to have found the relief that numerous doctors visits were not able to give him. So when Jordana was diagnosed with adrenal fatigue and hypoglycemia, he turned to the bees for treatment.

“I had nothing to lose, because I had tried everything else,” says Jordana.

Jordana stung the skin surrounding his pancreas and kidneys, two to three times a week, for about two and half months. It’s a regimen that he says relieved him of extreme dizziness and fatigue.

“It’s best to deliver stings dorsally. Anytime you give a sting, you want to do it away from any blood vessels. Capillaries by the fingers hurt so bad.” he says. “The best places are on the spine, shoulders, elbows and knees.”

Today, stinging is a part of Jordana’s regular health regimen. He helps others on their stinging journey, from neophytes to veteran stingers.

Power is one of those veteran stingers. But before starting her bee venom journey, she admits to being fearful of bees.

“I was always taught just to run away if you see one,” she says.

But her perspective shifted one day when tending to her vegetable garden, with her then two-year-old son.

“He was about the same height as the flowers, and he would just reach out and touch the bees,” she laughs. “He would pet the bees! So to see this little innocent child just petting the bees…it just sparked my curiosity.”

Marvin Jordana's bees buzz around their hive. (Video by Rachel Hallett)

Power’s initial experience with bee venom therapy was also unintentional. Her first backyard bee removal took several hours of grueling, physical labor. Power removed the bees from a collapsed shed, and was stung about seven times throughout the process. But when it was finally time to go to bed that evening, Power could not get herself to sleep. She felt an unusual surge of energy that went on for days.

Power was sold. She began intentionally stinging, focusing on joint areas that caused her chronic pain and patches of low-level skin cancer.

“It hurts, but it’s worth it,” Power says to Amanda Gonzalez, a first time stinger. Gonzalez takes Power’s place on the tree stump.

Gonzalez’s pain began about five months ago after a period of heavy lifting. She’s been feeling a dull, incessant pain in her joints ever since then.

Jordana prepares the bee on Gonzalez’s exposed arm; the bug balances just above her left elbow.

Jennifer Power receiving a sting. (Photo by Rachel Hallett)

“It’s like a sharp burning sensation,” says Gonzalez after receiving her sting.

“I love getting stung on the elbow,” Power says. “The elbow’s my favorite.”

For first time stingers like Gonzalez, Jordana tests for allergic reaction. He administers a test sting, one where he does not insert the stinger in too far and removes it immediately. He then monitors the person for the next half hour. If there are no adverse reactions, he’ll allow them to return another time for more stings.

The majority who come to Jordana for stinging suffer from chronic pain. They have been in and out of hospitals and doctors offices looking for relief. But to no avail. Some still seek an official diagnosis.

“You have to understand,” says Jordana, “Usually people do this when it’s a last resort.”

Brooke's Story

Brooke Geahan ran a successful magazine in New York. She played tennis habitually. She catered 100-person dinner parties. She lived an active, full and busy life.

Then in 2013, she suffered a tick bite.

While Geahan had been bitten before, this time was different. Her wound became inflamed, and developed a “bullseye” shape around it. She felt sluggish, achy and feverish. After immediately seeking antibiotics from her doctor, she was hopeful for a speedy recovery.

Instead, her symptoms escalated.

Intense fatigue began interfering with her work. She suffered migraines, neck pain, panic attacks, anxiety and night sweats. In the fall of 2013, Geahan fainted in public.

Geahan was diagnosed with chronic Lyme disease, accompanied with co-infections Babesiosis and Bartonella: all serious tick-borne illnesses. While Babesiosis and Bartonella can often be treated with antibiotics, Lyme is much more difficult to treat when not caught early.

Brooke Geahan at one of her many hospital visits. (Photo curtesy of Brooke Geahan)

“My Babesiosis test results came so high that the New York State actually did not release them for three weeks because they did not believe I would still be alive if those were correct,” said Geahan. “They just kept retesting. When they finally released the results to my doctor, an ambulance was sent to my apartment to get me because I should have been dead.”

Over the next couple of years, Geahan saw numerous doctors who treated her debilitating symptoms with countless combinations of antivirals, antibiotics and antiparasitics.

“They threw everything and the kitchen sink at me,” said Geahan.

Unfortunately, Geahan didn’t find relief with any of these treatments.

“I was bereft to find people that were understanding of it. I really became a case where doctors didn’t want me walking through the door - because they didn't know how to help me.” said Geahan. “I just started spending tens of thousands of dollars at a time - using up my life savings. But I was just getting sicker and sicker.”

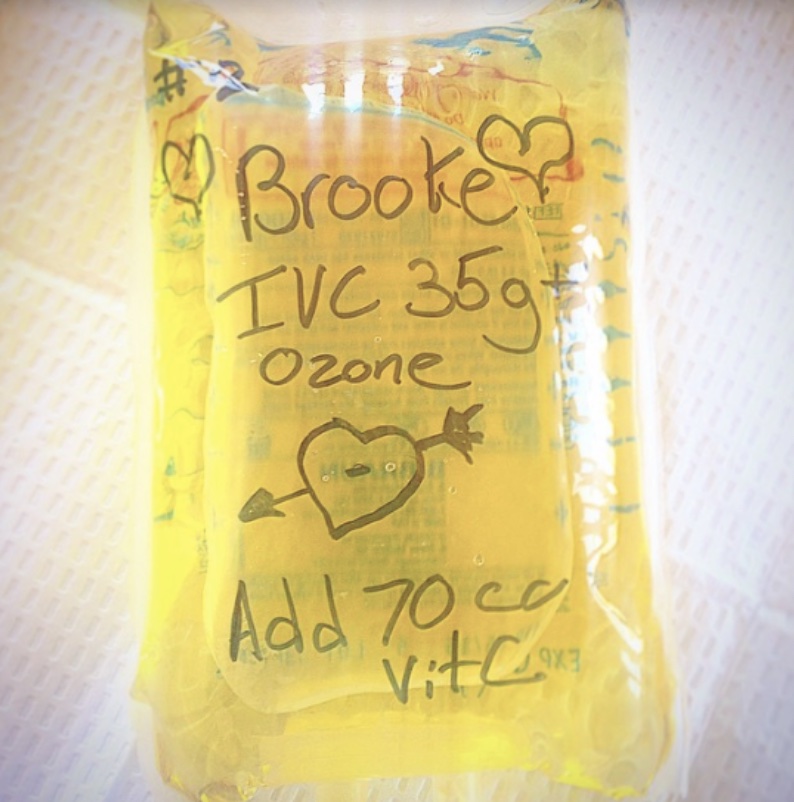

Brooke's ozone treatment, administered through an IV drip. (Photo curtesy of Brooke Geahan)

By 2015, Geahan felt abandoned and disappointed by her conventional doctors. She began seeking alternative therapies, like IV drip therapy, ozone auto-hemotherapy, IVIg and procaine injections, to treat her symptoms.

That’s when she discovered bee venom therapy through a nurse at a medical center in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

“Initially, I was like, ‘this is too woo-woo’. I’m willing to try anything, but not this,” said Geahan.

Until Geahan learned that this nurse had found success in treating her own Lyme disease with bees. And Geahan was hopeful that the nurse’s medical training would ensure both safety and efficacy.

“I convinced her to start stinging me,” said Geahan.

But Geahan didn’t want to be reliant on someone else stinging her. After learning the nurse’s stinging techniques, Geahan felt well enough to return home to New York.

Within six months, Geahan felt complete relief from her symptoms. Her lab results showed a normal level on her inflammation markers, a lowered pathogenic infection result and stabilized immune system markers. An outcome Geahan had never experienced under conventional medicine treatments.

Geahan stung approximately three times a day, for another two years. Slowly, she got her life back.

Today, Geahan is proudly Lyme free. But the experience has changed her perspective on the American healthcare system.

Some of Brooke's treatment regimen before beginning Bee Venom Therapy. (Photo curtesy of Brooke Geahan)

“With Lyme disease, you can easily go to 15 different doctors. But none of these doctors communicate with each other,” said Geahan. “So even if one doctor catches something, it can be missed by the others. There's this massive miscommunication happening, especially in complex, serious cases - like mine.”

Geahan’s journey with Lyme was the catalyst for starting her bee venom therapy retreat. The Heal Hive is a community for people living with chronic illness who haven’t found success in western medical practices. Geahan and her board of medical professionals teach Heal Hive members how to safely and effectively administer stings.

Brooke, now Lyme free. (Photo curtesy of Brooke Geahan)

“My last time in the hospital, I decided to call it on Western medicine and go full throttle for bee venom. I'm so glad I did,” said Geahan. “I owe everything to bee venom therapy. I do not think I would be alive without it.”

Geahan believes in treating with “nature’s perfect medicine cabinet”.

And she's not alone.

A strained healthcare system

A Pew Research study reports that one fifth of the American population has tried alternative therapy treatments in lieu of conventional medicine.

This is a trend that, Mojarad said, is likely a result of the United States’ current healthcare system.

“If you're a patient who has some sort of serious issue and you feel like your doctor is blowing you off, then going to someone like a naturopath,” Mojarad explained, “Someone who will sit with you, spend 45 minutes with you. That is very appealing. It has that emotional appeal. And unfortunately, our medical system is just moving away from that personal connection with people.”

But the alternative medicine world is shifting too.

Matt Brignall is a naturopathic physician and educator with over 20 years of experience in both alternative and conventional medicine practices. When he first began working in healthcare, Brignall was drawn to concepts such as hospice and palliative care - practices that were considered alternative medicine at the time. He describes these as part of a patient centered medical model, an archetype that he still believes in.

Some of these practices, once considered fringe science, are now adopted as conventional protocol.

“You look at standard treatments for Irritable Bowel Syndrome today - it’s fiber and probiotics. That wouldn’t have been the case 15 years ago,” he said.

But certain types of patients are more likely to seek out alternative medicine than others. Pew Research Center reports that patients with chronic conditions are often more likely to seek out alternative medicine.

“When you’re in a situation where you’ve exhausted everything that conventional medicine algorithms have to offer and haven’t gotten relief...It’s hard to understand what that desperation feels like,” Brignall said, “But I also think that if you’re a person in that place, you’re very vulnerable to fraud.”

"If they don't stand behind what they do. If they're only pretending at being doctor, but they're not actually doing the full responsibility of the job, then they fall into the Charlatan category for me.”

— Matt Brignall

This is a fear that Mojarad shares. And the consequences can be devastating.

“Pseudoscience gives people hope,” said Morajad. “I think that's the thing that most physicians, or anybody who has a loved one who has been susceptible to misinformation, gets irritated by...because it's quite criminal.”

Spotting dangerous alternative therapy can be tricky, but Brignall has a simple gauge for this.

“If something went wrong with a therapy, say on a weekend or off-hours, would you be able to get some sort of integrative service?” asked Brignall. “Because if they don't stand behind what they do. If they're only pretending at being doctor, but they're not actually doing the full responsibility of the job, then they fall into the Charlatan category for me.”

As of early 2022, nearly 20% of U.S. hospitals are critically understaffed - an issue exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. This labor shortage cultivates burnout, medical errors, risk of infection and poor patient care.

But a problem of this magnitude has origins more far reaching than the hospitals themselves. Brignall believes that politicians and public health departments play the Gepetto to the hospital’s Pinocchio. They operate a delicate set of strings that weave a twisted formula of decisions. Decisions with fragile and complex consequences that doctors, nurses and other medical professionals are left to cope with. And now, they’re strangled.

“I don't see you fixing the problem by specifically and only looking at healthcare,” he said.

The brokenness within the U.S. healthcare system fosters a feeding ground for patients seeking personalized care. Often, only those brave enough to spelunk the intricacies of this country’s healthcare system receive the proper and nuanced care they deserve. What that leaves is a generation of Boomers and aging populations that, Mojarad worries, will be abandoned in a system that doesn’t prioritize patients. In order to receive proper care today, the onus unfortunately lies on the patient.

“People really need to be their biggest advocates and push for answers,” she said.

But as the line between alternative and conventional medicine continues to blur, perhaps there is space for a new perspective in healthcare. Jordana believes the bees hold those answers as well.

Taking a note from nature

A swarm of honeybees can generate an electric charge of approximately 100 to 1,000 volts per meter. That’s about the same atmospheric charge of a thunderstorm cloud.

Jordana stands in the eye of this storm, holding a frame of the lingering, squirming bees and glistening golden honeycomb with his bare hands. A creature that once frightened him, was bringing him new life.

“If you come into a beehive feeling angry or upset, they can sense that, just like a dog would,” he explains. “The bees meet you where you’re at.”

Marvin Jordana's bees crawling on their honeycomb. (Video by Rachel Hallett)

Jordana’s land is positioned only about a mile from the I-5 freeway in Los Angeles, but it’s impossible to tell. There is no semblance of city life here. All that can be heard is the low hum of the bees, as they zip and whiz through the air in unison.

And that’s how Jordana likes it.

“I like to think of apiaries as acupuncture points throughout the city,” Jordana says. “Because something special happens when you put bees in a yard.”

When Jordana first came to this area, this patch of land looked very different.

“We didn’t even know there were almond trees here. Those never blossomed until the bees came,” he says.

When the bee venom therapy session comes to an end, Jordana stands behind each of the participants with a set of chimes he says were blessed by a Tibetan monk. He clinks the chimes together above the participant’s head and moves them slowly outward. The soft ring echoes down the eardrum. He does this as a way to reset the body after a stinging session. He says that it establishes a balanced synergy between the soul and the body, just like the bees and their environment.

Amanda Gonzalez receives "reseting ceremony" following bee venom therapy in Los Angeles, California. (Video by Rachel Hallett)

Jordana believes that bees offer a glimpse into a harmonious working ecosystem that humans have rejected.

“Bees don’t have an ego. There’s not one bee trying to keep more honey than the other bees. They’re symbiotic,” Jordana explains. “The bees never separated themselves from the environment, and look at them...”

Jordana gestures to a bee, delicately drying its antenna on Power’s hand.

“They’re thriving.”

A bee rests on Jennifer Power's hand in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Rachel Hallett)