One day, after a long cry in the shower, inspiration struck Rachel Sunday. "People just feel better after they take a shower — after they workout, after they cry — a shower just makes you feel better," she said.

Access to cleanliness is a fundamental human right — one that is not afforded to many homeless Angelenos. This necessity compelled Sunday to act.

“Fighting homelessness is not for the faint of heart.”

— Mayor Eric Garcetti

Three years ago, Sunday launched The Power of a Shower, a service that provides a clean, safe space for the unhoused to bathe. The importance of this volunteer effort is reinforced every week when she leaves her home in Westchester and aids those in need in Venice. The Power of a Shower is one of many different programs addressing the homeless crisis in Los Angeles, which affects a reported 66,436 individuals in various neighborhoods across the city.

In many ways, these solutions reflect the character of our city: there is conflict because each region has diverse opinions, people, backgrounds, and concerns. Yet all neighborhoods are connected by similar challenges: access to resources, shelter, and a permanent pathway to housing. When policies differ from council districts to blocks, how do we move forward with a unified approach?

- The bohemian area of Venice in West Los Angeles is the high-profile backdrop to controversy surrounding homeless encampments and shelter.

- The port city of Wilmington, home to a sizable Latinx community, offers refuge to the homeless through public-funded housing developments. Are working-class neighborhoods targeted to support the city’s systemic housing insecurities?

- In South Los Angeles, 825,808 residents make up an expansive racial identity. We look at foster youth; minors who bear unique barriers and obstacles compared to the general population. Are foster care youth and at-risk children falling through the cracks into homelessness or are their needs met with long-term support?

"Fighting homelessness is not for the faint of heart," wrote Mayor Eric Garcetti in an email to us. Garcetti, President Joe Biden’s nominee for ambassador for India, will leave behind a conflicting legacy regarding homelessness. On one hand, he has pushed through a $1 billion budget earmarked for homeless initiatives. On the other side, residents are demanding progress and clean streets, while homeless advocates frustrated by anti-camping laws are calling for more direct and consistent outreach and services.

"The very essence of mutual aid is understanding that the system doesn't work," said community rights and homeless advocate, Zen Sekizawa. "It's a way to work outside the system … which is essentially criminalizing people who are poor."

The COVID-19 pandemic magnified conditions among homeless adults and children. Many financial and educational services for foster youth were suspended, including housing, court closures and delays.

"Kids maneuver homelessness," said Michelle Dewberry, a social worker for Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services. "It is common; they will take a shower at the gym, hang at a friend’s house or at school for an extended period so they are not exposed to the streets."

Hope With a Little Soap

Photo courtesy of The Power of a Shower.

Audio: On site with Rachel Sunday and The Power of a Shower.

Blue tents line uniformly along the winding boardwalk in Venice. Jangled electronics, heavyweight blankets, and an assortment of kitchen appliances are visible. Passersby gaze and move on.

It's 72 degrees; the sun is shining, the ocean whispers beneath an upbeat soundtrack of rock and pop classics, and the odor of marijuana hangs heavy in the air. A bubble machine pumps soapy suds high into the deep blue sky. No, it's not the parking lot of a Phish concert circa 1983 — it's a Thursday morning in Venice Beach in 2021. The nonprofit organization The Power of a Shower has set up shop right off the boardwalk, ready to provide a relatively private place for the unhoused to rinse off.

Sunday first felt an inkling to work with the unhoused after attending a media and tech networking group. She heard a speaker discuss the ever-present issue of homelessness in Santa Monica and Venice and started to ruminate on how she might help: "I knew I wanted to do something, but I didn't know what I wanted to do."

Sunday works in health insurance and constantly hears people pushing for free health care. Free health care would be fantastic in the U.S., but she muses that not everyone has access to water, let alone other necessities to live a comfortable life. "If you're thinking about giving everyone in the nation something, we should start with the basics like water and hygiene," she said.

Every Thursday at 6:45 a.m., Sunday and her assistants, 26-year-old daughter Haley "Xandy" Novack, and husband Aaron Sunday, set out for the 300 Ocean Front Walk parking lot in Venice. Sunday and her daughter drive to the beach stocked with undergarments and socks donated by Bombas. Meanwhile, her husband collects the trailer that houses the organization’s three showers from the nearby Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant in El Segundo.

Sunday and her staff make it clear that they have no allegiances to government organizations, including law enforcement. Their devotion lies with the people they serve each week. She takes this bond of trust seriously. "We will never snitch on anybody. We will never involve the police," she said. "If the police are looking for somebody and are walking toward us, we will erase the name-board. We are there specifically for the people."

Photos courtesy of The Power of a Shower.

Around 8:15 a.m., everything is set up to begin taking down the client's names. Not everyone will get a shower; only the first 30 people in line are guaranteed a spot. The other 75 or so do not go away empty-handed. Each receives what Sunday calls a "hygiene kit" containing Q-tips, a bar of soap, body wash, shampoo, shaving cream, toothpaste, toothbrush, and a razor.

All they need now is to find running water, which is surprisingly not easy to do. It was especially true during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic when the city closed beach bathrooms and turned off the water. Many of the unhoused resorted to drinking out of the houses of Venice residences, and encampments sprang up not only along the boardwalk and beach but on sidewalks as well. The conflict between residents, businesses and the unhoused had reached a boiling point.

We need better street hygiene. The city shouldn’t remove any existing, functional sinks or toilets until we’ve approved & funded a better program. We need more restrooms, open 24/7, with staffing to make sure they remain clean. https://t.co/0n3fg7cHHf

— Mike Bonin (@mikebonin) July 14, 2021

A plan to dismantle the encampments in Venice is in progress but has proven more challenging to implement than anticipated by city officials, some of whom raise concerns about ongoing public health concerns. Mike Bonin, the Los Angeles City councilman representing Venice and the 11th District, said in a tweet: "We need better street hygiene. The city shouldn't remove any existing, functional sinks or toilets until we've approved & funded a better program. We need more restrooms, open 24/7, with staffing to make sure they remain clean."

The Power of a Shower has chosen to stay out of politics and take an impartial stance. "We just want to be like little fairies. We want to go out there and clean people up and make them feel good for 15 minutes, then miraculously show up next Thursday," Sunday said.

Existing hygiene stations have been removed citywide but there is momentum to continue similar work. According to Councilwoman Nithya Raman’s communications team, specialized outreach teams are being formed and sanitation units with ''Pit Stops'' are being secured. The Pit Stops will include hand washing stations and toilets, essential hygiene services that are a critical component of public health, helping to reduce the spread of communicable diseases and COVID-19.

Across from The Power of a Shower, a smaller but mighty crew of volunteers offer food and other essential items to those in need. Hopes for the Homeless, run by retired couple Pam Connolly and partner Joel Post, serves breakfast three times a week and dinner once a week to Venice's downtrodden. Whole Foods donates the breakfasts, but otherwise, all expenses, including clothing and other health items, come out of their pockets.

Xandy Novack

Anonymous

Pam Connolly

Connolly has always cared about others and worked as a medical assistant. What first brought her attention to the unhoused epidemic was her experience living in New York, taking care of a man who lived right outside of her apartment. "When I lived there, I took care of a homeless man. Every day I would go to him, he'd eat … and I stayed with him until he passed away," she said.

The pair run the gamut from pet sitting to helping individuals navigate the complex web of governmental benefits, as well as staying by their side during doctor's appointments. "You have to have an advocate with you, or you get lost in the system and fall through the cracks very easily," she explained.

Connolly has seen it all. She has cleaned wounds, cared for burn victims, and even delivered a baby — all on the streets armed with only her supplies and a whole lot of love. "We just want to show love and care," she said. "That is our main objective – to let them know someone really does care about them. Someone loves them. And it's us!"

Safe Port in the Harbor

In Wilmington, at 1355 Avalon Blvd., a chain-link fence cordons off a dilapidated building long past its 1950s supermarket heyday. Signage from shuttered business endeavors — drinking water distribution, a taqueria, a discount store — adorn the building's patchwork-painted exterior, and nine seafoam green pillars jut upwards from the facade like a comb set upright on its spine.

This 34,300-square-foot site is one of 13 permanent supportive housing projects currently in the pipeline for District 15, home of the Port of Los Angeles and its neighboring communities. It's also a source of contention between homeless advocates, government officials and some residents who believe that the focus on homelessness supersedes other economic opportunities beneficial to the community.

"This doesn't help our economy. This doesn't generate revenue. We need businesses," said Valerie Contreras of Citizens for a Better Wilmington, a group that has collected nearly 6,000 signatures in a petition against homeless housing projects in the city. "We have no Starbucks; we have no place to shop; there's no Target. Everybody leaves Wilmington and takes their tax dollars somewhere else," she said.

Two blocks west of the site on Fries Ave. (pronounced "freeze"), community activist Alicia Baltazar regards the 1355 project as another burden unfairly shouldered by Wilmington's roughly 60,000 residents, 49% of whom earn less than $50,000 annually, according to U.S. Census figures.

"You're supposed to have five of them [HHH projects] in your district, why are three of them in Wilmington?" A better solution, Contreras said, would be to take advantage of the property that the city already owns.

"That property has been vacant for 10 years," said Council 15 District Director Gabriela Medina. "Development like this in Wilmington has not happened in over a decade. There's a need for this type of housing now."

The development, shepherded by property management company Brilliant Corners, will include on-site case management services for tenants. Vanessa Luna, the firm’s director of a multifamily supportive housing development, said it is part of her mission to provide this type of housing and get people off the streets. "It’s a part of the solution to the homelessness crisis we're facing," she said.

1355 Avalon is one initiative in city Councilman Joe Buscaino's goal of providing a safe shelter system that can support at least 60% of the unsheltered population in District 15, or approximately 1400 individuals, according to his housing plan. A Bridge Home, Safe Parking and Tiny Home Villages are also among the multipronged approaches to sheltering the 585 homeless individuals in Wilmington. The developments are funded in whole, or part, by Measure H, a ten-year county sales tax plan to produce $355 million annually for investments in housing, shelter and street outreach, which would benefit foster youth as well.

Robert Cox, a gregarious man with a raspy voice, panama hat and wayfarer-style sunglasses, is currently sheltered at the Bridge Home project in Wilmington and is making a point to keep a roof over his head. "If you get in a place, you sit, you drink, whatever the hell you're doing, you sit in a corner and don't make no effort, nothing's going to happen. You're going to be back out on that corner." He continued, "If you go out there and put in a little legwork, show them you want something, you might get a little help."

That help, according to another recently housed individual, Mary Carson, affects the unhoused at a fundamental level: "I finally got a good night's sleep."

The Hidden Face of the Unhoused

'The Great Wall of Crenshaw,' Los Angeles. Courtesy of Creative Commons.

Audio: Listen to Markeesha's story.

Markeesha, who prefers to disclose her first name only, is a 37-year-old South Los Angeles native. She entered the foster care system just short of two years old. Markeesha has seen a lot and has dealt with the emotional impacts of transferring through multiple foster care homes to group facilities. Through it all, she has persevered.

Markeesha grew up in an area that stretches south from Watts and Compton and west across Interstate 110 into Inglewood, the Crenshaw District, and Baldwin Hills.

In a time when massive amounts of crack cocaine began flooding the streets, these ramifications left irreversible damages on Latinx and Black communities in more ways than one. Some youth, much like Markeesha, witnessed their parents' habits result in death, drug dependency, or jail. Her parents struggled with drug addiction and were susceptible to the perils of the revolving door of the criminal justice system.

Markeesha, the youngest of three siblings, wasn’t confronted with the same challenges as her brother and sister. "I didn't get to experience too much of being dragged in the streets as what I hear now, but my older siblings, they did," she said.

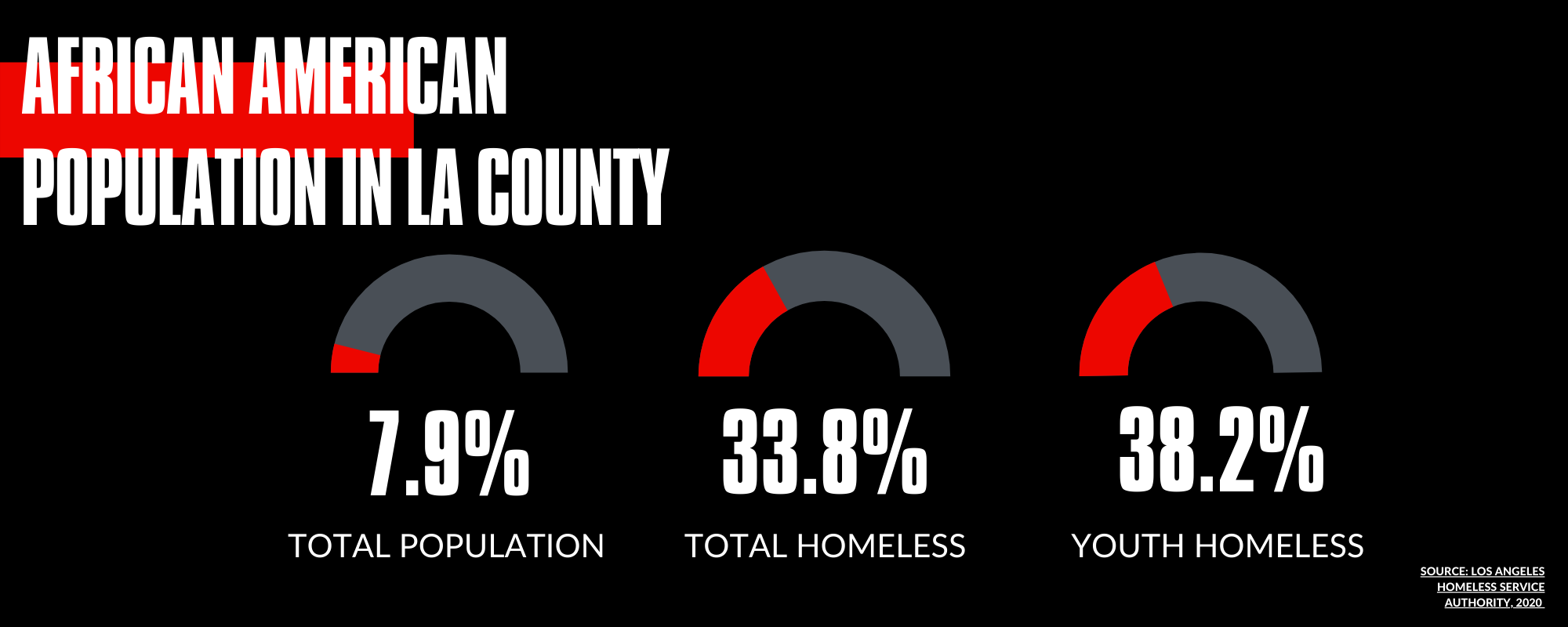

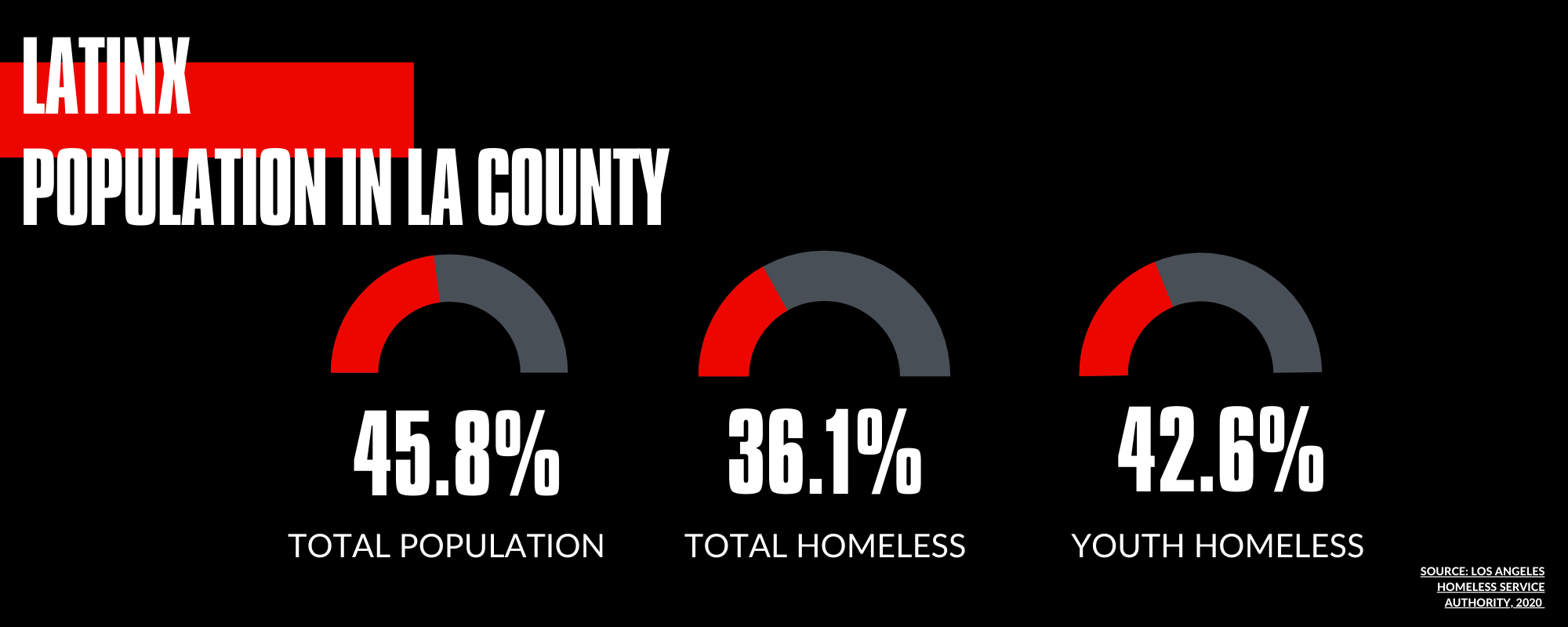

South LA is largely populated by Latinx and Black residents. This speaks to the alarming rate of young person’s experiencing homelessness in South LA. The homeless count among youth has risen from 644 to 1,094 in just one year: 57% of South LA's unhoused youth was identified as African American; Latinx rated the second-highest population. A disproportionate number also points to homeless youth who are more likely to be female.

"For children who have been in the system a long time, [they] have experienced transitions in placements where one placement stops, and they move on to another – they often end up in a group home or a residential setting," said Dr. Jacquelyn McCroskey, a professor of child welfare at the University of Southern California.

McCroskey discussed the trauma that foster youth experience: "There are just incredibly traumatic circumstances where the foster family is not what we thought they were or when conditions in the group homes, either with the staff or with other youth, become problematic."

The lack of guidance, as well as neglect, can lead foster youth to fall victim to the juvenile justice system. This was Markeesha's story.

"I went to juvenile hall … I always wanted to fight people," Markeesha said.

Five days after Markeesha’s 17th birthday, she gave birth to her daughter, and her outlook began to change. "It struck home once I had my daughter. That's when reality set in, but I was still being a little naive. I was on probation. My mom went to jail while I was pregnant. I was sleeping from the pillow to [the] post stand while I was pregnant. I was doing my own thing, raising myself," she said.

Markeesha and her daughter lived in the Florence Crittenton Home in Lincoln Heights, which is now closed. She later moved to Gramercy Housing Group, located in the Crenshaw District.

Gramercy House, Los Angeles. Photo by Alysha Conner.

"Once I went to the group home with my daughter, one social worker just broke me down," Markeesha said. "She was like, 'You have a child that you have to take care of. This attitude, this persona you're putting on like you don't want to talk to nobody … you need to let that go. You need to open up.'"

Markeesha broke down: She cried, but grew accustomed to expressing herself. "It was like a release of just all these built-up emotions," she said.

Determined, Markeesha began to see her own potential. She attended community college and continued at California State University, Los Angeles, where she received a bachelor's degree in social work. Her daughter followed in her academic footsteps and is attending a four-year college.

Markeesha has been working full time at a human rights organization and hopes to open her own group home for young girls and offer them the same support she once received. Not all homeless youth possess the same grit as Markeesha, but many stories of homeless adults begin like hers.

A Community of One

James, Los Angeles. Photo by Sarah Wolfson.

Imagine living on the streets with all of your belongings and being constantly uprooted by city sweeps. Languid, moving from one place to the next, trying to find rest: Does such a space exist? We are tasked with the responsibility, as Angelenos, to be a part of the conversation, shift the narrative and find safety for our neighbors.

The founders of The Power of a Shower and Hopes for the Homeless will argue that they have done nothing extraordinary, nothing that any one of us couldn't do on our own. They have simply treated a population of the otherwise forgotten as humans. Maybe that is what has been missing in the battle against homelessness the entire time.

As one frequent client of Sunday's said, "It's just a little taste of humanity ... It's a nice thing for people to come out and bless us with showers. Something that should be a necessity."