The re-emergence of queer nightlife in West Hollywood

A rainbow flagged culture still lacking color

By Alexandra Applegate, Andre Lawes Menchavez and Madeline Quiroz-Haden

Rainbow flags and neon signs illuminate the streets of West Hollywood (WeHo) as patrons line up outside of recently reopened bars and clubs. WeHo has always been a staple for queer nightlife in Los Angeles, but among many members of the local Black and Indigenous people of color (BIPOC) community, it’s also a staple for a certain kind of queer nightlife — one that caters to and idealizes white gay men.

The last year forced BIPOC communities to bear the burden of witnessing racialized violence impacting their community members, from the re-amplified Black Lives Matter movement after the killing of George Floyd to the Stop Asian Hate movement following attacks on the Asian community nationwide. Further, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected communities of color, adding to the looming threat to BIPOC queer lives. According to the CDC, Black people are still twice as likely to die of COVID-19 than white people and have accounted for 34% of deaths despite being only 12% of the U.S. population.

Nightclubs have always served an escape for the queer community amid death and violence. In the ’80s, during the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, members of the queer community were dying from a virus that incited social and systemic mistreatment toward queer people. Much like the pandemic today, the AIDS epidemic violently impacted communities of color, with many unable to access care and services to survive. Black and Latinx people survived shorter periods of time from AIDS than white people. Queer people of color would then rush into packed dance clubs and steamy bathhouses as their chosen families and partners died, seeking affirmation and solace from those similarly experiencing their traumas.

"We're supposed to be welcome here, but it's tough...especially the darker you are."

Today, nightclubs offer a similar escape from violence. But for many club patrons of color in white dominated spaces like WeHo, the exclusion and mistreatment in these clubs are violent themselves. The renewal of queer nightlife has illuminated the need for more BIPOC queer spaces as the world tries to emerge out of the COVID-19 pandemic and search out community again.

Lindsey P. Horvath, mayor of West Hollywood, says community members of the city have expressed their concerns about inclusion. “For a long time, we had heard stories anecdotally about whether it was perceived tacit exclusion or active exclusion from spaces [in West Hollywood],” Horvath said. The issue has heightened so much that the city is addressing it on a governmental level, creating a Social Justice Task Force to address these issue that have been meeting regularly since May.

Dr. Eric Gonzaba, assistant professor of American studies at California State University, Fullerton, is writing a book about the evolution of queer nightlife. Exclusion runs generations deep according to Gonzaba’s research, which notes histories of nightclubs racially discriminating against African American patrons, serving people of color last at the bars and the traumatic sexual fetishization of people of color by white gay men. With these histories in mind, Gonzaba said spaces for queer people of color are culturally and personally important.

“BIPOC spaces exist in a place where they’re markers of acceptance for a lot of people who feel like ‘gay’ has become synonymous with [being] white,” Gonzaba said. “For so many Black, Latinx and other queer people [of color], to find places for themselves where they could find other people like them was liberating.”

The sight of WeHo today — where maskless patrons dance to electronic beats and stumble from one bar to another — exudes an image of a pre-pandemic world where seemingly nothing has changed. BIPOC community members are demanding more than a return to normalcy; instead, they want a revitalization of what once was, combating histories of whiteness in queer nightlife and even making spaces of their own.

Dr. Eric Gonzaba, assistant professor at California State University, Fullerton

Listen to Dr. Eric Gonzaba, a historian of race and sexuality in America, explain how nightlife became so important to the LGBTQ+ community and why minority groups self-segregated.

Santa Monica Boulevard is populated with restaurants, bars and clubs and often has rainbow signs or coloring to represent the LGBTQ+-friendly atmosphere in West Hollywood, Tuesday, Aug. 10, 2021. (Madeline Quiroz-Haden)

Reclaiming body and space

At QNA LA’s Pride weekend celebration — where “body” was the theme in celebration of all body types — two artists presented an “experimental queer art performance” involving one of them getting naked while dancing in the pool as the other waited outside of it with a towel. As the wet body of one performer powerfully emerged from the water, the other dried them off. The piece culminated with their two vulnerable bodies of color joining in an embrace.

“That is QNA right there,” said Jonathan Crisman, one of the five creators of QNA LA. “Caring for one another.”

QNA LA, which is short for “Queer n’ Asian,” was created by Louie Bofill, Jonathan Crisman, Paulie Morales, Ly Tran and Howin Wong in 2019. Since, the collective of queer Asian excellence has hosted various events showcasing and providing space for queer Asian community members. “I wanted to create space for people who were like me, who didn’t know where they belonged,” Boufill said.

QNA LA also offers cultural celebration and community healing. Morales and Ly both said their events have extended interpersonal support after surviving their traumatic upbringings feeling like the “other” in their communities. “We grow up harassed, called names and there’s a lot of trauma that comes with that,” Tran said. “As adults, we create this space for each other. We are creating this community that is a family that we didn’t have growing up.”

The community culture fostered by QNA LA is striking in comparison to that of WeHo’s, which has often left folks of color feeling the cold sense of ostracization that they attempted to escape from in the heteronormative outside world.

“I’ve experienced situations in West Hollywood where I don’t feel like I fit into the mold, and it’s not always the most welcoming for people who don’t fit that mold,” Morales said.

The notorious “WeHo mold” of the white, gay, muscular man is something that QNA LA has actively tried to demolish, providing space for women, femmes and lesbians –– especially for those who are of color. “I was super proud of our last party on Pride Weekend because there was a really strong femme and female presence,” said Crisman, QNA’s self-proclaimed ‘party mom.’ “It’s sadly very rare to have queer spaces that are welcoming to folks who are coming to that kind of space… QNA is what we were looking for. It didn’t exist, so we made it.”

Luna Deathwish poses with some of her tips at the end of her performance in Highland Park, Sunday, Aug. 8, 2021. (Alexandra Applegate)

Joella Perry dances and lip-syncs during her number at Send Noodz in Highland Park, Sunday, Aug. 8, 2021. (Alexandra Applegate)

Bibi Discoteca, host and co-founder of Send Noodz, motions to the crowd for applause in Highland Park, Sunday, Aug. 8, 2021. (Alexandra Applegate)

Drag Race Thailand host Pangina Heals suprises Send Noodz attendees with a cameo in Highland Park, Sunday, Aug. 8, 2021. (Alexandra Applegate)

Cultural wealth beyond tokenization

Further East of West Hollywood in Highland Park, Bibi Discoteca welcomed a masked and vaccinated crowd of attendees at Send Noodz’s first in-person show since the pandemic began: “Let’s honor our past ancestors, us right now, and the future generations that we are cultivating! Let’s have a good motherfucking show!”

Discoteca and Miss Shu Mai are two drag artists who created Send Noodz, LA’s first monthly Asian Pacific Islander drag show, which started in March of 2019. Queer people of color that found home in their events valued the safety that white-dominated spaces like WeHo rarely provide.

“It’s really a safety issue,” Kari, an attendee of Send Noodz, said. “I personally feel a lot safer in spaces that are specifically for melanated people because there are certain things that white people specifically don’t understand… In terms of really being able to relax and be our authentic selves, it’s easier to do it in a space specifically for melanated people.”

Miss Shu Mai shared with the crowd that the purpose of creating Send Noodz came after noting both her and Discoteca’s experiences in the LA drag scene — they were often the only people of color in a club’s lineup of drag performers. They shifted from tokenization to the creation of a community that empowered cultural wealth and healing that was unmatched by their white counterparts.

“Specifically being around people of color, especially other Asian folks and performers, it’s just a different kind of healing,” Lyn, another attendee of the event, said. “[Send Noodz] was a lot more conscientious than a lot of other queer events I’ve been to. There are a bunch of wealthy cis, het, white folks, [that] might be queer, but it’s not as relatable. No matter what, even if there was a sense of relief and ‘healing’ [that white-led spaces claimed to provide], at the end of the day, it was not my community.”

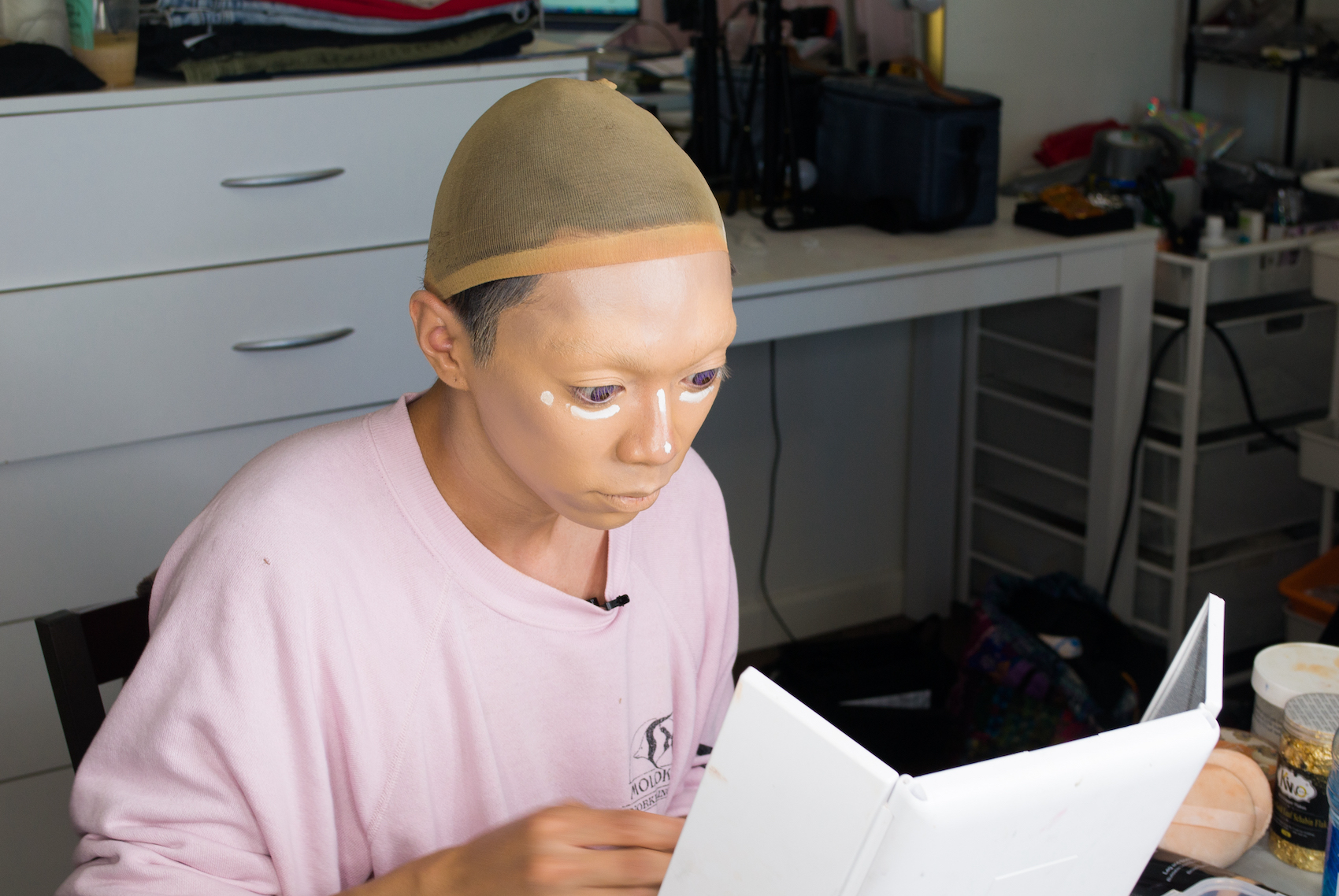

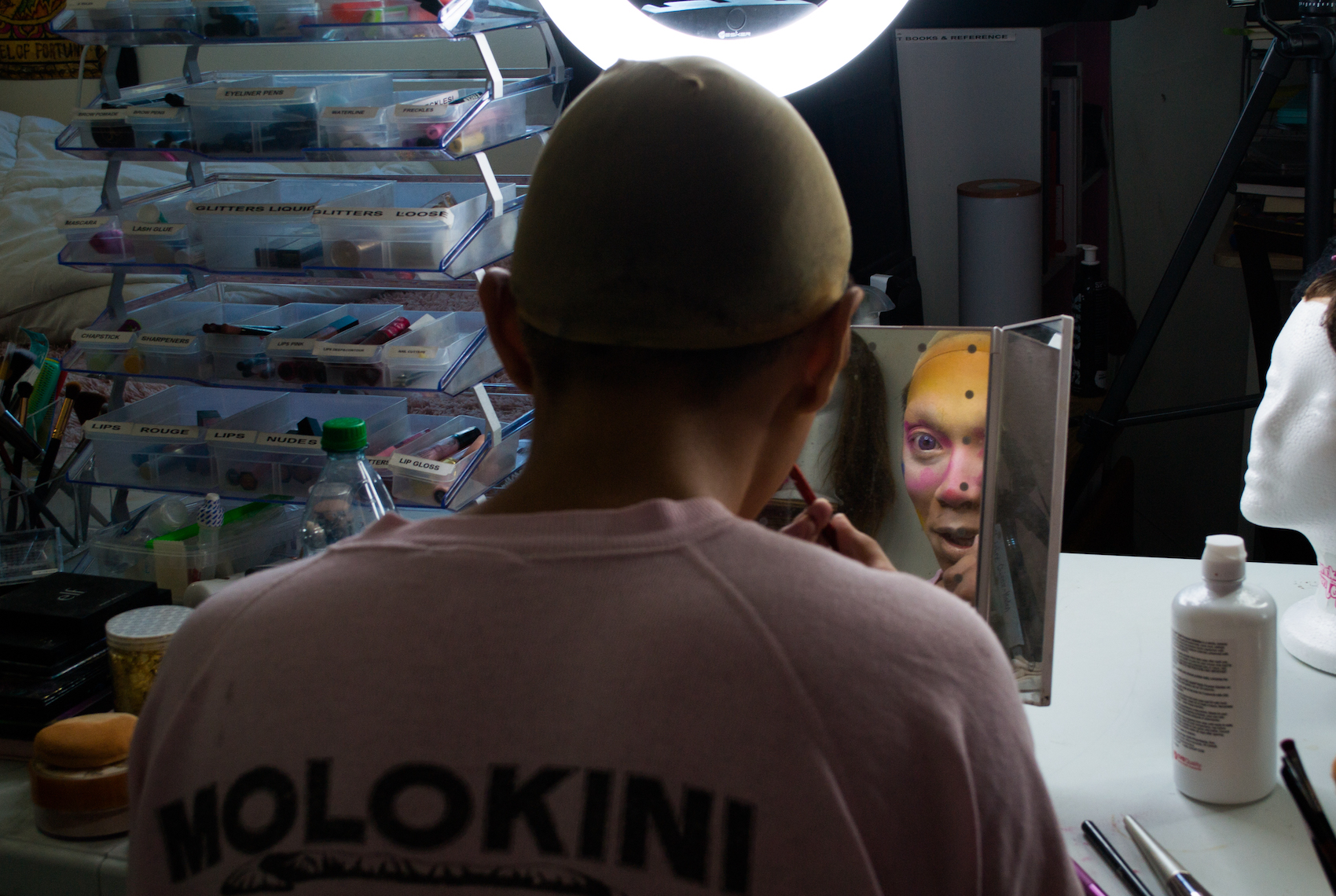

Lea Salonganisa, Asian drag artist, starts the process of getting into her drag makeup by applying foundation in Culver City, Monday, Aug. 2, 2021. (Alexandra Applegate)

Salonganisa applies blush on her cheeks in an eccentric fashion in Culver City, Monday, Aug. 2, 2021. (Alexandra Applegate)

By adding swatches of blue and yellow across her face, Salonganisa hopes to give the appearance of a cartoon or an art piece in Culver City, Monday, Aug. 2, 2021. (Alexandra Applegate)

As the final step of getting into drag, Salonganisa puts on her wig in Culver City, Monday, Aug. 2, 2021. (Alexandra Applegate)

Stolen humanity and the 'fantasy'

Painted in full drag and adorned with Asian cultural garments, Lea Salonganisa performed at one of Send Noodz’s virtual shows in March with a piece titled “MOVIES.” Salonganisa, whose namesake comes from Filipinx cultural references (Lea Salonga, a famous Filipina broadway singer, and longanisa, a sweet sausage that has become a staple Filipinx delicacy), powerfully lip-synced to a song as depictions of Asian violence projected onto her. The performance was created during the height of the Stop Asian Hate Movement, shortly after the Gold Spa shootings in Atlanta in March of this year that killed 8 people.

“Everything I do comes from a love of my people,” Salonganisa said. “The performances I do can be really cultural, it’s inescapable. It’s my whole identity, it’s my experience and it comes through in my art.”

At QNA’s rooftop Pride weekend party, Salonganisa came dressed illuminating her bare body with only a few pieces of duct tape placed on her as a garment. Her earrings, nails, and headpiece were entirely made from the duct tape, strikingly contrasting with the bright water-color style makeup on her face.

“That kind of stuff is celebrated at Send Noodz and QNA,” Salonganisa said from her Los Angeles home while transforming –– or what she called the process of “feeling her fantasy” –– into her drag persona. “Our humanity is more celebrated.”

Performances like hers are applauded in spaces cultivated by and for BIPOC queer folks, a sentiment not shared by much of WeHo’s drag scene. “In West Hollywood, you won’t see stuff that I do,” Salonganisa said. “You go to West Hollywood and most people are thin, white and glamorous. There’s not a lot of alternative art happening.”

According to Salonganisa, the last year involved tension between alternative drag artists and the cisgender queens of WeHo, which does host transgender performers but still has a lot of work to do to incorporate more diversity in the scene. She believes that what’s missing in WeHo is “a certain anti-racism.”

Using drag as an art form for social commentary, Salonganisa painted her skin yellow, attached a prosthetic rat’s nose on her face and created an outfit made of torn pages of Edward Said’s book, “Orientalism,” to address the anti-Asian rhetoric used against Asian people at the start of the pandemic. She performed this at a drag event where white gay men sat in the front row. Salonganisa said she felt the men were visibly disconnected and unamused at her showcase of cultural commentary and vulnerability. She found this treatment to be jarring in comparison to her white drag queen peers who get applauded in these spaces for performances that are less culturally inspired than her own.

“If you’re a white queen, you can go on stage and eat a hotdog — I’ve seen that shit — and people will eat you up,” Salonganisa said as she painted asymmetrical lines from her palette onto her face. “It’s glorious to a mainstream audience. But if you’re me, and you’re talking about getting called a virus, no one’s living... I can’t transverse a lot of places that white and cis-assumed people can float in between.”

Some crosswalks along Santa Monica Boulevard are painted with rainbow-colored stripes in West Hollywood, Tuesday, Aug. 10, 2021. (Madeline Quiroz-Haden)

The future of queer nightlife

As the sun set in WeHo and patrons began entering bars and clubs down the rainbow-colored street, folks shared what they thought about the culture of the city –– from their favorite spots to grab a drink to their opinions on the racial diversity of those who take space in them. Some patrons felt WeHo was perfect and inclusive as is.

“I’ve come here for three years, it’s open for everyone,” one patron named KeShawn said. “Sticking together, not seeing color… it’s great, I love that!”

Another patron named Erin mentioned how going to the famous gay bar, The Abbey, is “where it becomes an issue.” He recalled the time it takes for him to get a drink at the bar is quick, but for his Black friends, it takes a much longer time. “We’re supposed to be welcomed here, but it’s tough,” he said. “Especially the darker you are.”

Despite the mixed opinions of WeHo residents and visitors, local officials are still opting to shift the diversity landscape to a more progressive one.

“The status quo is exactly that, it’ll always be until we intentionally do something to change it,” Mayor Horvath said. “My intention in [creating the Social Justice Task Force] was to help create a space where action could be taken to create a future that is truly inclusive of everyone who we want to come to West Hollywood and see themselves in our community.”

“The reality in West Hollywood is that [about] 80% of our population are white folks and about 20% are from the BIPOC community,” said Councilmember Sepi Shyne, who took office in 2020 as the first out LGBTQ Iranian elected in the nation, and was a pivotal leader in the creation of this taskforce. Its establishment was long overdue after years of rising rates of white demographics in WeHo –– both inside the bars and in the surrounding neighborhoods.

At the task force’s recommendation, the city council has already passed incentives for BIPOC business owners in the area. For communities of color who lack generational wealth to create their own spaces, this means everything.

“We don’t have the funding to really fully do what we want,” said Tran of QNA. “Of course, people with money, like rich white men, are opening up spaces and it’s unfortunate that we have to try and get our foot in the door by saying, ‘Hey, can we have a Thursday night at this bar?’”

The founders of QNA said they only sometimes make back the money they spend putting on their events. Despite this, they’ve given all donations from patrons to the collective to mutual aid funds for other organizations. “We’re doing this as a labor of love,” Crisman of QNA said.

As nightlife reemerges and stray masks blow down the streets of WeHo where patrons leave the thoughts of the pandemic behind, queer people of color are remembering how it felt to be the token drag artist in a lineup of white performers or the fetishized object of a white man’s attention at a packed white gay bar.

“This is made by our community for our community,” Miss Shu Mai said, taking in the crowd of BIPOC queer people finding solace in the community she’s created in front of her. “This is a testament to our resilience as queer communities of color.”

This time, with the help of collectives of color like QNA and Send Noodz, queer people of color’s stories and cultures won’t be swept under the rug of a bar floor. Instead, they will be amplified in spaces of vibrant color, by people of color.