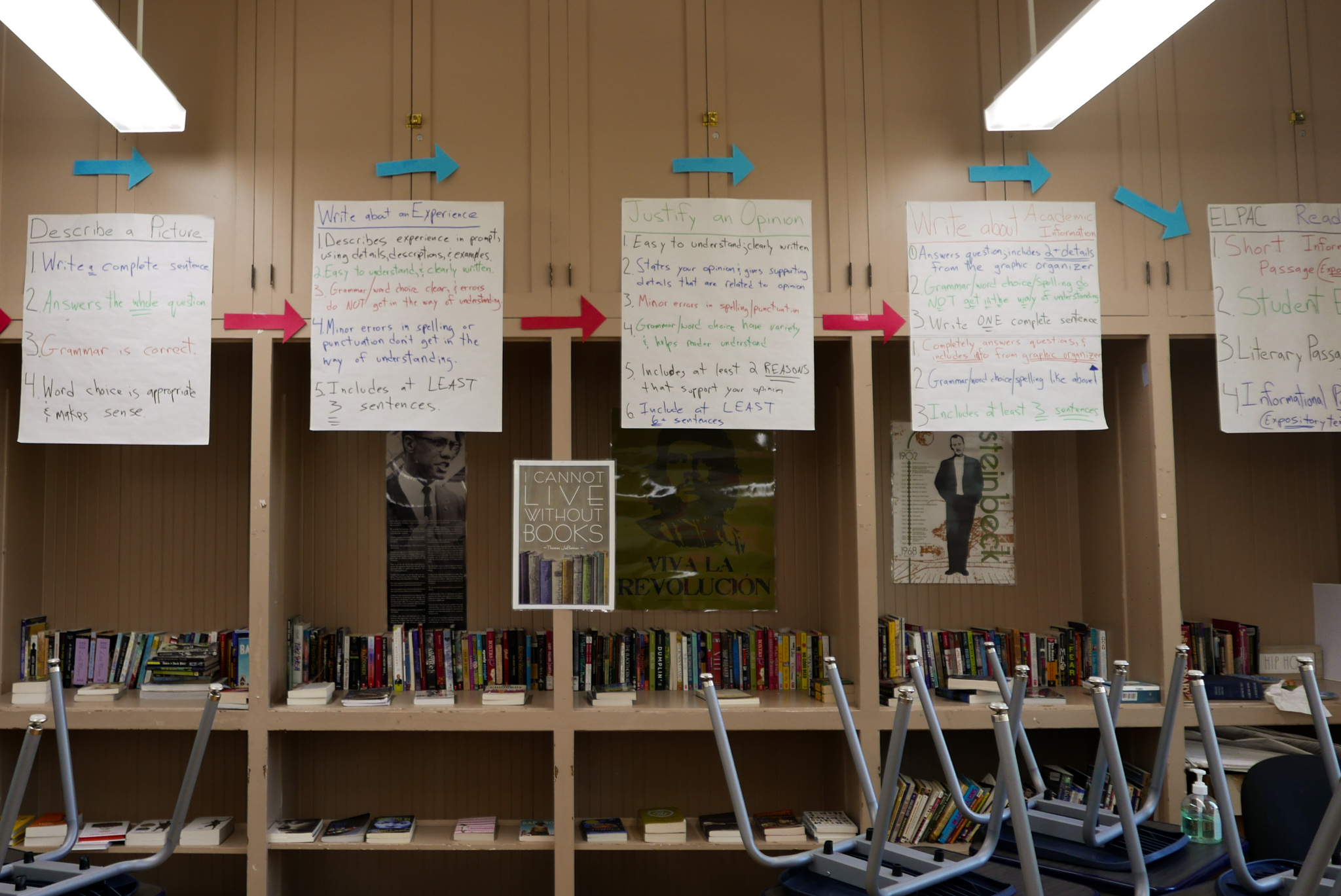

On the first day of class, Alfredo Resendiz likes to scare his students at John Muir High School. The new cohort of freshmen excitedly shuffle into his bright and airy classroom, with north-facing windows that look out toward the San Gabriel mountains — the same mountains that I drove past every day on my way to school. In the back of the room, posters of Che Guevara, John Steinbeck and Malcome X are tacked to the wall above built-in bookshelves. Resendiz is an English teacher.

When the students take their seats, Resendiz, a tall man with a beard just beginning to sprout white hairs, establishes the classroom rules. In particular, his no-phone policy. It’s important to him that students avoid distractions in class...That’s the first day.

The next day, he softens up a little. It’s a get-to-know-you day, where students talk about where they’re coming from and why they chose John Muir out of the four public high schools in Pasadena, California.

Resendiz asks, why Muir? Most respond because of their friends. He asks a tougher question. “How many of you didn't want to come?”

Some students are there by accident. They preferred Pasadena High School or one of the other schools in the district, but they missed the enrollment deadline. Most of those students will leave by the next year, Resendiz said.

Once they settle in, Resendiz asks, “Okay, what did you hear about Muir?” This is when the students come out with all the descriptions: it’s a bad school, it’s ghetto, there are fights, there are gangs.

“I heard those same things when I was 13,” Resendiz, who was a student at John Muir in the 1990s, said. “Narratives really embed themselves in the psyche of a community.”

At John Muir High School, only 34% of students in the attendance zone are enrolled. Court-ordered integration in 1970 forever changed Pasadena’s school system. Enrollment at John Muir and other schools dropped dramatically. In the ‘70s, there were over 2,000 students enrolled at the school. Today, there are less than 1,000. Over the last 50 years, white and middle-class families fled Pasadena’s public school system in favor of the many private schools in the area, leaving schools like John Muir underfunded and under-enrolled. Funding is tied to enrollment.

Muir was once a majority-white school. But, pre-integration, it was also one of the most diverse schools in the district. In a majority-white city, the students once reflected the place they lived. Now, there are only 43 white students at John Muir. The student body is predominantly comprised of Latino and Black students. At John Muir, 85% of students qualify for free or reduced lunch, while the average household income in Pasadena is $85,000.

Low-enrollment and segregated schools are a reality throughout all of California’s public schools. These two issues dominate educators’ daily and long-range plans, as public school enrollment declines, leaving low-income students in a broken system. California is the most segregated state for Latino children in the country, according to the UCLA Civil Rights Project, with 58% of Latino students attending “intensely segregated schools.” Since 2014, public school enrollment in the state has declined by 6%. Last year, California lost over 100,000 public school students.

In recent years, gentrification warped Pasadena’s school system as well. Families who lived in the area for generations are moving to Lancaster or San Bernardino. And, the birth rate in the city is declining. The future looks bleak. “For schools to keep existing the way it exists with declining enrollment is just not feasible,” said Dr. Julie Marsh, a professor of education policy at the University of Southern California’s Rossier School of Education.

In Pasadena, there is a group of parents, primarily white parents, who are pushing to bring white and middle-class students back into the public school system. But at John Muir, teachers, students and administrators are wary of these efforts. Who will benefit? This is the internal conflict for many at the school: bringing students back into the school will increase enrollment and through enrollment, funding. But will those students who are already in the public school system benefit as much as the new students?

In Resendiz’s classroom, with its north-facing windows, the discussion of “why John Muir,” inevitably turns into a conversation about race and diversity. The class begins discussing why it’s a Black and brown school. Some students said it would be better if there were more white students at the school.

Then one student, a Black boy, raised his hand. “Why,” he asked. “I'm okay with school, and I haven't had a white kid as a classmate for a long time.”

There are two Pasadenas. After bussing began in the 1970s, a slew of private schools popped up. Now there are 44 private schools in the district. Just over half of Pasadena school-age children attend private school — I was one of those kids. The other 49% go to public schools.

I grew up in Pasadena, mostly unaware that another city existed in unison with the one I was experiencing. I spent my entire life in private schools, in classrooms primarily filled with white students, and primarily taught by white teachers.

“There are some deeply rooted racial tensions in this community” Monica Lopez told me. “And segregation and racism that was built into the setting up of the community,” she said. Lopez is the marketing director of the Pasadena Educational Foundation, a non-profit set up to help the public school system with fundraising and support because the district can’t sustain itself on its own. To understand these racial tensions, it’s important to start at the beginning.

Pasadena was founded in 1886, as a resort town for wealthy tourists. As the population grew at the beginning of the 20th century, the city attracted Mexican, Japanese and Black workers who mostly settled in the Northwest section of the city. That’s where John Muir High School was founded in 1926 as a technical high school, focusing on trade skills rather than college preparation.

“Muir was actually designed to be a place to put minority kids who they assumed were not going to need college prep,” said Pablo Miralles, a John Muir Alumnus (‘84), and a filmmaker who has been studying the school system's history for his documentary, “Can We All Get Along?”

When the 210 freeway was built in the 1960s, it tore through neighborhoods where Black and brown families owned homes, moving many of these families north to Altadena. The city became more segregated.

Then, in 1970, a court ordered in favor of the plaintiffs in Pasadena City Board Of Education vs. Spangler. The class-action suit included one Black family, the Clarks. They lived in a big house on Altadena Drive. Incidentally, some 40 years later, I grew up in the house next door.

A bussing program began and the schools in Pasadena were officially integrated. While violence erupted across the country, in Pasadena, things were fairly peaceful. “It wasn’t a Black or white thing. We all got along,” said Allen Edson, who was a student at John Muir when the school was integrated and is the current Pasadena NAACP president. “It was a beautiful experience we had,” he said.

Allen Edson recalls what it was like growing up in Pasadena when court-ordered intergration was instituted

When Resendiz returned to the school as a teacher in 2005, it felt like a homecoming, he said. But, this was a tough era for John Muir. At the beginning of the new millennium, the school went through five principals in six years. Test scores were so low that the state intervened, and in 2008 all the teachers and staff were required to reapply for their jobs in an effort to turn the school around.

At the time, the state intervention was framed as a state takeover in the media. But Resendiz said the school was never as bad as it was made out to be. For him, the problems at the school didn’t define his experience as a new teacher, which was overall positive.

“There were issues with gangs and fights and drugs,” said Resendiz, “But nothing more than when I was a student.” Gang culture has also diminished since the’ 80s and ‘90s, Resendiz said.

In 2009, Resendiz left the school and taught in Pomona for several years, working at a charter school with students ages 16 to 24. When he returned to John Muir in 2018, the school climate had changed. “The numbers, the participation, the spirit of the school, the energy of the school had kind of diminished,” he said. In 2008 there were 1,300 students at the school. Within 15 years that number dropped by 400 students.

In the 1990s, years before Alfredo Resendiz became a teacher at John Muir High School, he was a student at the school.

A year after Resendiz left John Muir in 2009, Pasadena Unified School District instituted a school choice program, which allowed students to enroll in any school in the district. But school choice was another means for families to further disassociate themselves from John Muir and other public schools in the district.

In the United States, school choice programs were a reaction to Brown vs. Board of Education, Marsh, the education professor, said. “It was a way for white families to avoid integrating.” In Pasadena, parents can choose where to send their children. That means they also choose where not to send their children.

“School choice is a disaster,” Resendiz said. School choice means that 66% of high school students living in John Muir’s attendance zone go to other Pasadena public schools.

In the 1990s, to address low enrollment issues throughout the entire district, Pasadena Unified started adding magnet programs to various schools. Some schools specialize in science or music; others have dual-language immersion programs. John Muir recently became an early college magnet school and began a dual-enrollment program with Pasadena City College. Now, students can work towards an associate degree while still in high school. PCC has a satellite campus on Muir’s campus.

There is a Pasadena City College satellite campus at John Muir. Students enrolled at the school can complete associate degrees while still in high school.

Reluctantly, Resendiz acknowledges that this program succeeded in attracting families to the school. Historically, magnet programs, such as dual-language curricula, have benefited white and economically advantaged students.

Lauren Gray, a current John Muir 10th grader, attended a Chinese-English dual-language program at Field Elementary School in West Pasadena. The program was introduced at Field to save the school. At the time, many of the district’s elementary schools were closing. Lauren was one of the only Black students in a sea of white and Asian students in the dual program. But, those weren’t the only students at the school. The mainstream school program still existed, said Lauren. And those students were all Black and brown.

“It’s almost like there were two different schools,” she said. “It almost seemed as if the other kids were being pushed aside.” Lauren is the daughter of John Muir High School’s principal.

Resendiz simply wants programs that benefit the students already in the school system. Why fund programs to attract students who aren’t there and might not come, and instead fund the students who are there? “I believe in neighborhood schools, and I believe in funding lower socioeconomic neighborhood schools in a way that makes it not equal but equitable,” he said.

To increase enrollment, John Muir recruiters go to events for prospective high school students. I remember going to one of these as a middle school student. All the Pasadena private schools have tables where they pass out expensive brochures printed on glossy paper. There are pictures of happy students lying on grassy patches reading books, or walking under brick archways.

John Muir now attends some of these events. They are the only public school that does, said Lauren. She was once at one of them, acting as a school ambassador when parents came up to her and started asking questions. What’s the school’s ranking, one asked. Another parent asked, is there a lot of cursing at the school?

Years before this event, Lauren was at the predominantly white and Asian Sierra Madre Middle School, when a music teacher joked that Lauren would be shot at John Muir High School, where she planned to attend.

“I feel like a lot of people are very misinformed, and they have this interpretation of public schools, even though they might have not even stepped on a campus or seen the campus,” she said.

Lauren is top of her class, sophomore class president, a member of the Black Student Union and a dancer. She is also enrolled in John Muir’s dual-enrollment program with Pasadena City College, where she is working towards two Associate degrees. One is in Gender, Ethnicity and Multicultural Studies, the other in Social Justice. Lauren will complete these degrees while in high school.

Lauren Gray is top of her class, a dancer and sophmore class president.

Yet, despite all of her accomplishments, Lauren is sometimes too aware of her school's reputation. Perhaps this is because she’s the principal’s daughter. She has endured the maligning of her school just as much as the teachers and administrators.

While in middle school, a math teacher told her it was a good thing she was going to Muir because they needed good students like her. There’s this idea that students at Muir do poorly academically, she said. But these comments also make Lauren doubt herself; is she a good student, or is she just a good student for John Muir?

“I'm top of my class, but I sometimes question it,” she said. “If I go to another school and not even a private school, like if I just go over to Arcadia, will I still be doing that good?” That is why, in room A122, Resendiz asks his students about going to John Muir. Lauren sees how people undermine her school and her peers and why they undermine it.

“There's a big contrast between the public and private schools, and I know when people only see the Black and brown side of the public schools, that is automatically a ‘no’ for them.” In Pasadena, public schools are associated with low-income and minority students and poor academic performances. “It’s all about what people hear and who they hear it from,” she said.

When Susan Schwartz first joined the Parent Education Network (PEN) in 2008, the group’s sentiment was clear but unspoken. White families were going to band together to rejoin the predominately Black and brown public schools in Pasadena. Now, in retrospect, Schwartz sees the complications of that impulse.

While uncomfortable, it is not uncommon. Studies have found that white parents need a school to be 25% white before they feel comfortable. On the New York Times 'Nice White Parents’ podcast, journalist Chana Joffe-Walt calls this “the bliss point.” Many of the trends in Pasadena’s school district — such as language immersion programs — are examined in Joffe-Walt’s work, where she uses a Brooklyn public school as a case study.

Cindy Guyer, a member of PEN, could send her children to private school if she wanted to. But she chose Pasadena public schools because of their diversity, she said. Her two children attend Marshall Fundamental High School, on Allen Avenue, east of Pasadena’s historical dividing lines, Lake Avenue. In Pasadena’s public school system, Guyer believes that discrimination affects who enrolls at the school.

“I think there's a little bit of discrimination at various levels,” she said. “Not only income, but race as well and there's discrimination against people with disabilities.” At Marshall, 20% of the students are white.

Organizations like PEN have affected public school enrollment. “I've seen tremendous change in who's going to the PUSD schools and the reputation of the schools improving dramatically,” Jennifer Hall Lee, school board member for the 2nd District, said.

But this sense of improvement doesn’t include John Muir. “The PEN and PEF situations haven't really changed us a lot,” said Resendiz. Schools like Marshall are perceived as ‘safe,’ while John Muir is still seen as a dangerous school to outsiders, he said. But, Resendiz also said that there are some ‘front-line’ families coming back to Muir.

Nadia Elhawary, a school counselor at John Muir, noticed this change in the freshman class. Elhawary was a student at Muir from 2006 to 2010, during the state intervention.

“Gentrification is the number one reason why the class is turning white and wealthy and why I see less Black students here,” she said. Between 2019 and 2021, white student enrollment has increased by 180%. For Elhawary, it is important to acknowledge that gentrification hurts Black students even more than Latino students, she said. “A lot of brown families own homes,” she said. “Black folks haven't had the same access because of racism in housing.”

Integration is often treated as a panacea for a broken public school system. But for people who grew up in Northwest Pasadena, who went to Muir and now teach at Muir, they are concerned about who will be erased in the process.

“I wonder who is going to benefit,” Nadia said. “It makes me a little nervous.

Dr. Lawton Gray, the school’s principal, is also concerned by the framing of the integration argument. He disagrees that students of color need white students. “You don't need 30 percent white students to do well,” he said. Instead of trying to attract white and wealthy students to John Muir, Gray wants to take care of the students already enrolled, and building a school with a great reputation will naturally attract the missing students. And, with gentrification, they’re already beginning to appear anyways.

While qualitative data suggest integrated schools close the achievement gap, the movement is sometimes misguided. Marsh came to learn this in a lecture she was teaching. She made the assumption that integration was a value every person in the room shared, she said. Then a student, a Black women, raised her hand and said, “I would be happy with high quality, segregated schools if you could just provide the high-quality teachers and the well-resourced school buildings.”

Integration is not necessarily the cure-all it’s made out to be. Or, at least the cure-all I assumed it was. And the lengths that it takes to attract wealthy families to the public school system often lead to some students being pushed aside. But, if public schools are the first place where students experience democracy, as School Board Member Hall suggested to me, then they need to represent everyone in that democracy.

Gray, also recognizes the benefits of a diverse, expansive, educational experience. “I think the one thing it does change is the experiences of getting to know other cultures,” said Gray. If schools were properly integrated, would Lauren Gray still have to answer the questions that grown adults pose to her?

Either way, progress in Pasadena is slow, enrollment increases are slow. And Gray isn't sure people in Pasadena are ready to give the public school’s a second chance.

“Some white people are not ready to come to a school with a lot of Black students,” he said. “And some Black people with money, and Latino people with money are not sure about coming to a school with low-income Black and Brown students.”