Freediving: An Overview

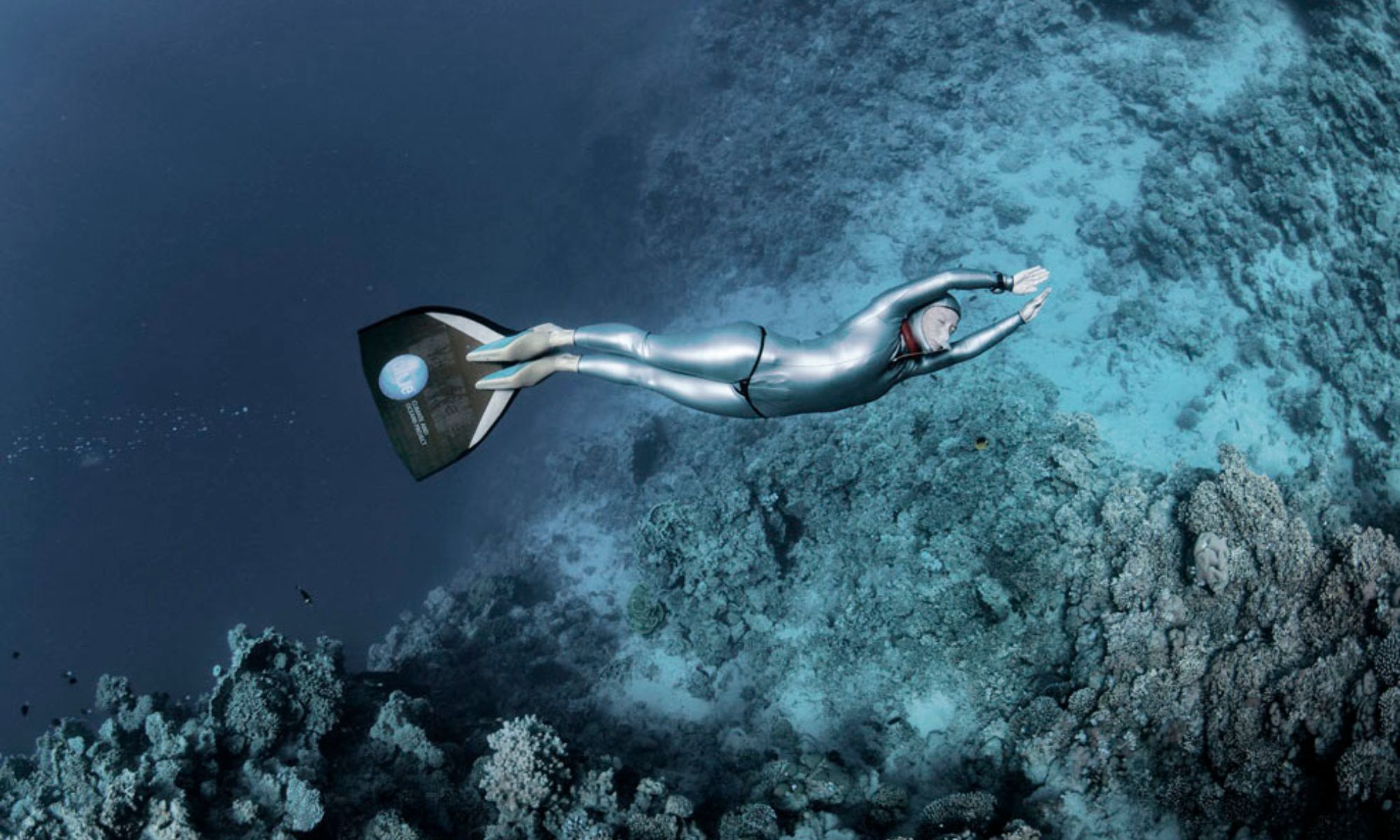

Freediving is one of the world’s most dangerous extreme sports. While deep-sea divers face extreme risks that can be life-threatening, there’s a reason they pursue it.

With a passion that, they say, is sometimes hard to put into words.

Sure, there’s the thrill. And the lure of records that stretch the limits of the human frame and our imagination. How deep can a person go? Without breathing — for how long?

Yes, it’s all that.

But what it also is, say those who have been there and done it, experienced the depths and returned to life as we know it, is profound.

It’s the feeling of being alive — purposefully, vibrantly alive.

While at the same time feeling — and knowing — the calm of inner peace.

Without that peace, a diver at extreme depths can perish.

So being down at 50, 60, 70, 100 feet and more, amid the green kelp forests, feeling the never-ending rhythm of the sea, is a lesson in meditative calm.

“Freediving is an incredibly meditative process for me,” Davis said. “It’s very much something where I'm focused on the moment at hand and I'm not trying to think ahead. I'm really trying to be blank when I do a dive.”

The History

Freediving, also known as skin diving, is an extreme sport that relies entirely on breath-hold until resurfacing. A diver swims without scuba gear or a snorkel.

While freediving may be a relatively young sport — sport defined as we moderns might — it goes back to the dawn of recorded time, since the first human ventured beyond the waves.

Through the ages, humankind embraced the sea as a source of survival, innovation and inspiration.

Humans have been freediving for more than 8,000 years. While studying Chinchorian mummies, people who lived in what is now modern-day Chile, archaeologists discovered signs of exostosis. Exostosis, also known as surfer’s ear, is a benign growth of new bone that grows on top of existing bone to protect the eardrum from exposure to cold water. This indicates the Chinchorian people spent much time in what we now call the Pacific Ocean.

Alexander the Great was known for being heavily involved in diving apparatuses. During the Siege of Tyre in 332 BC, he used a diving bell to send humans underwater to dismantle barricades protecting the harbor in the Mediterranean Sea. Alexander is one of the earliest known users of the diving bell, a rigid cage that traps air, allowing a diver to take multiple breaths while submerged.

The Greeks were certainly no stranger to the water. Surrounded by the Ionian, Mediterranean and Aegean seas, the Greek people have been diving for at least 4,000 years. The Minoan civilization, which flourished between 3000 to 1450 BC, left behind ceramics made from shells and scripts and artifacts that feature images of the ocean. In ancient Greek manuscripts, Homer and Plato mention the sponge as part of the bathing ritual. The Dodecanese island of Kalymnos was the commercial center of sponge diving for centuries. How would they get them? Using a skandalopetra, which is a marble or granite stone to collect sponges, divers would descend up to 30 meters beneath the surface to gather sponges.

In 1913, Greek sponge diver Stathis Hatzis dove 88 meters, or 288 feet, to locate and tie the anchor of the Italian battleship Regina Margherita, which was said to have been lost. His dive lasted four minutes and was the first recorded freedive.

Recorded modern freediving again resurfaced in 1949 when Raimondo Bucher dove for 30 meters to the bottom of the ocean near Naples, Italy, on a wager. Quickly, other divers stepped up to the challenge, reaching depths that would leave Bucher far behind.

Italian diver Enzo Maiorca reached 45 meters in 1960.

Robert Croft was another influential player in the timeline of freediving. Known as the Father of American Freediving, Croft was a U.S. Navy diving instructor who could hold his breath for up to six minutes. He developed the lung packing technique, which forced extra air into his lungs for a deeper hold during a dive. In 1967, he dove more than 60 meters, which at the time seemed impossible.

In 1988, Maiorca reached a depth of 101 meters.

His rival, French diver Jacques Mayol, had set another world record in 1983, diving 105 meters. Maiorca and Mayol’s rivalry is depicted in Luc Besson’s 1988 film, “The Big Blue.”

After Maiorca, Mayol and Croft came Francisco Pipin Ferreras and Umberto Pelizzari.

Ferreras reached 128 meters in 1995, 170 meters in 2003. Umberto Pelizzari trained under Jacques Mayol and set 16 world records, including 150 meters in 1999.

Austrian freediver Herbert Nitsch currently holds 33 world records in all eight freediving disciplines. He surpassed his previous 2007 record of 214 meters by pioneering 253 meters – 830 feet – in 2012. He is known as “The Deepest Man on Earth.”