LOS ANGELES — Athletes capture our attention when they can persevere, adapt and bounce back from experiences that might take others down.

They almost never do this alone.

Much of their resilience comes from athletic trainers and physical therapists who guide them through difficult workouts, painful recovery sessions and a shared ambition for excellence. By pushing their clients, the best sports medicine teams have developed a reputation for preparing athletes for challenges.

But how resilient are these enablers of excellence?

After the pandemic froze sports, it became clear that athletes’ livelihoods had been placed on hold. For the backstage figures who make elite-level sports possible, the repercussions are only now becoming clear. That is especially true of the ecosystem of sports preparation and medicine. COVID-19 forced athletic trainers and physical therapists to adapt on the fly, leaving them to show whether they too were resilient on a professional level.

“There were quite a few within the profession that got laid off,” said Dr. Zachary Winkelmann, a clinical professor and education coordinator at the University of South Carolina. “No one knew what to do, or when it [sport] was going to come back.”

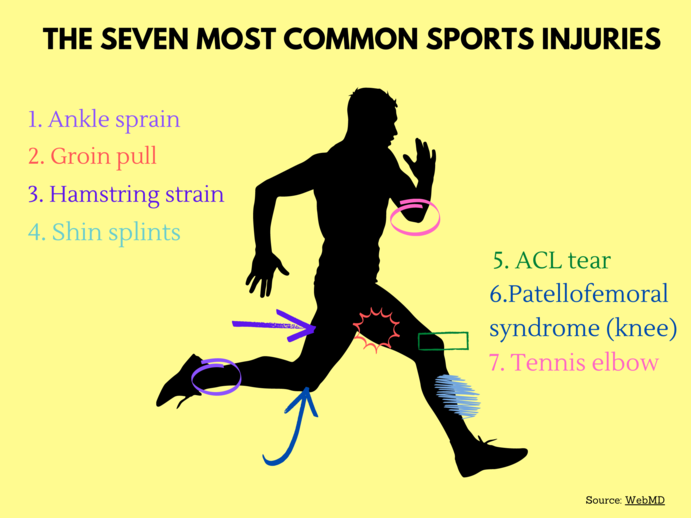

No sports meant no more sprained ankles, pulled hamstrings or shoulder impingements. Fewer injuries meant a downturn for the professionals responsible for treating and preventing these ailments.

The U.S. Bureua of Labor Statistics reported that employment declined for all health care practitioners by 1.4 million in April 2020. In a study he published in the Journal of Athletic Training, Dr. Winkelmann found that roughly one in every five athletic trainers were unable to work during the pandemic — a great deal of highly-trained, highly-educated individuals found themselves unable to do their jobs.

“Many athletic trainers kept their job titles but their jobs looked completely different,” said Winkelmann.

Clients stayed away from physical therapy, too. The dip in patients meant less business for sports facilities. For many staffers, fewer clients meant less work, reduced pay and sometimes temporary furloughs.

“When the pandemic first started, we probably lost 50% of our patients,” said Dr. Justin Brouhard, senior physical therapist and center coordinator of clinical education at Sports Academy in Thousand Oaks, Calif. Brouhand works with patients with orthopedic diagnoses.

Those who remained on duty implemented new COVID-19 protocols — wiping down work stations, filtering the air and even hiring cleaning crews to come in up to three times a day to sanitize. These measures failed to bring clients or patients back.

Partly, that is because a lot of injuries were not happening. Even weekend warriors who play in pickup games or adult softball leagues found themselves barred from courts and fields. Skipping physical activity means a lower sports-related injury potential — which means a lower chance of needing a physical therapist.

On top of this, non-essential surgeries were either postponed or skipped, and nervous patients delayed or cancelled general checkups.

“Hospitals at the height of the pandemic got completely away from all elective surgeries,” said Dr. Ky Kugler, Chapman University professor and president of the California Athletic Trainers' Association. “That included orthopedic, musculoskeletal-type surgeries. Clientele for rehabilitation from a knee operation or a hip replacement didn't exist.”

"Many athletic trainers kept their job titles but their jobs looked completely different." — Dr. Zachary Winkelmann

For physical therapists like Brouhard who usually treat patients recovering from elective surgeries, this accounted for a lot of empty physical therapy rooms.

At Sports Academy, while the sports medicine professionals retained their medical team, the athletic performance department had to make some difficult decisions as state regulations shut down sports facilities. “The state was not clearing performance training at the time,” said Brouhard. “There was just no work.”

All this undercut the bottom lines of health businesses, hospitals and, in many cases, the income of practitioners.

Less discussed have been the sports medicine fellows and students that graduated into a world without sports. The suspension of elective surgeries and in-person treatment decreased clinical practice for students, a demographic that was already facing a historically bleak job market.

According to a study in the Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, the pandemic compelled many students to remain in school for extra semesters; many others had job offers rescinded.

Evidence suggests that young professionals entering a recession job market face repercussions that extend far into the future — higher unemployment rates, lower average earnings and greater likelihood of needing government help.

“Many of our students,” said Winkelmann, “have returned for advanced degrees. For them it’s a huge risk. Like, ‘What if I invest my time in a program that I may not even get to practice skills with patients [in-person]?’”

These students face a potentially taxing outlook. Young adults often face the steepest unemployment rates during economic turmoil. Those with the least experience are often cut first or hired last.

Yet, amid the changing vista, those in the sports medicine field pivoted from their specialties and expanded their breadth of treatment. The reason can be traced to their underlying ambition: take a solution-oriented mentality and move forward.

WATCH: The post-pandemic injury boom has begun.

Pivot or Perish

An early concern for many professionals in the sports world was the disappearance of their profession. The ability and willingness to shift their focus to community and public health services put that worry to rest.

“The challenge has been to be flexible. To be able to pivot in almost any direction at any time,” said Kugler, who oversaw a slew of changes to the athletic training program at Chapman University.

Part of this flexibility has been the introduction of telehealth on a broad scale. Early in the pandemic, the American Physical Therapy Association and the American Medical Association began to include telehealth under insurance policies.

Many patients felt more comfortable with remote appointments as opposed to in-person sessions, and more than 40% American Medical Association of athletic trainers engaged in telemedicine.

Physical therapists saw a similar digital uptick. Sports Academy saw a steep rise in telehealth appointments during the first 90 days of the pandemic, explained Brouhard.

Remote sessions helped, but did not fix every problem. Communicating digitally can be more difficult for both client and practitioner, and injuries cannot be touched or manipulated in the same way.

Though he felt some of the efficacy decreased — movement analyses and muscle palpations can be difficult over Zoom — Brouhard acknowledged it was a suitable alternative for patients worried about the virus.

Those without the ability to hold telehealth appointments experienced a different pandemic altogether. Many sports medicine professionals went to where the greatest need was: the front lines of the COVID-19 response.

They're Not Just "Sports People"

Many athletic trainers are incorrectly dismissed as individuals with an education that does not extend beyond the goal lines. They can be shrugged off as mere coaching assistants, the ones responsible only for taping bum ankles and furnishing ice packs.

“Athletic trainers are so well-educated and trained in communicable diseases, infectious diseases,” said Kugler. “We were very, very well suited to transition to other avenues of health care.”

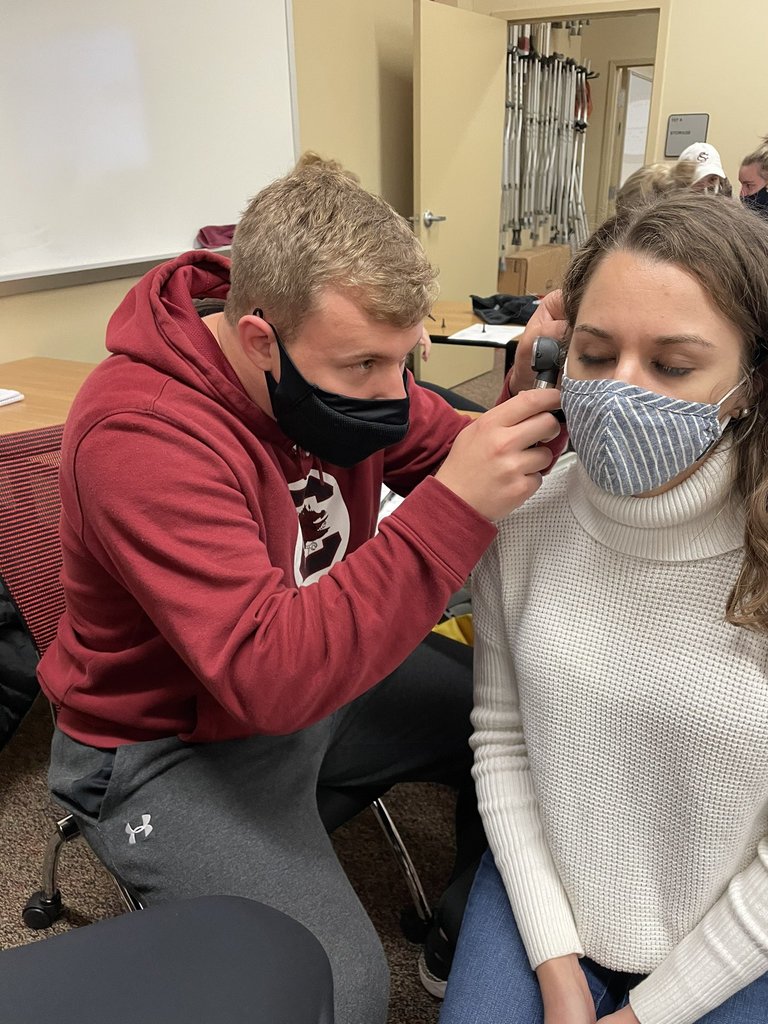

Athletic trainers often have graduate degrees, thousands of hours of clinical experience and must pass a comprehensive certification exam. Their curriculum includes rigorous courses such as anatomy, physics and chemistry.

As president of California Athletic Trainers Association, Dr. Kugler has studied industry trends closely this past year. He watched athletic trainers adapt at every level — high school, college, professional and even those who worked for the military or hospitals.

"We were very, very well suited to transition to other avenues of health care." — Dr. Ky Kugler

Kugler described an athletic trainer at Cal State Fullerton who devised creative workouts for the water polo team — which she delivered virtually. Some athletic trainers went into emergency rooms, providing triage for physicians and nurses. Members of the San Diego Athletic Trainer Society addressed the need for platelet donations during the pandemic by assisting at blood drives.

At the university level in South Carolina, Dr. Winkelmann pushed his students to apply their clinical skills to the pandemic. This provided meaningful, productive work while sports were on pause. Many of his students and staff, which the state deemed essential workers, were trained to administer vaccines, conduct COVID screenings and organize contact tracing.

“Athletic trainers were taking on new responsibilities because a lot of times they were the only ones around trained to do certain clinical tasks,” said Winkelmann. “We’ve been able to integrate into vaccination sites as part of the solution for the community’s COVID response.”

In his research, Winkelmann found that athletic trainers largely maintained resilience through the pandemic — defined as the “process of adapting in the face of adversity or significant sources of stress.”

The results suggest that, in the face of a rapidly evolving professional landscape, athletic trainers remained steadfast. “The athletic trainer became almost like a gatekeeper of preventative medicine for places that didn’t have a public health professional,” said Winkelmann.

A Cautious Next Step

There is a new, more pressing worry now that a year has gone by and sports have gradually returned: After months of deconditioning and relative inactivity, athletes are more vulnerable to injuries.

Even for those who specialize in treating athletes, the abrupt return of athletics presents a challenge that today’s professionals have never encountered. The resurgence of sport threatens to further strain the healthcare professionals who have been warring against the coronavirus all year.

“From a deconditioning standpoint, I would say it’s created a significant increase in injury,” said Brouhard. Long sedentary stretches can decrease musculature and increase body fat percentage — all which exacerbate injury risk.

Playing sports after months off means more injuries. Brouhard estimates that Sports Academy has had more than a 20% increase in patients coming in with injuries in April compared to the previous month.

Those who postponed surgeries or received vaccines have since flocked to schedule treatments they had put off. Post-operative rehabilitation duties usually fall upon the shoulders of physical therapists, who now must handle this alongside the post-pandemic injury-boom.

“I had no new [patients with] ACL reconstructions for probably four to six months,” said Brouhard. “Within two weeks after they opened doors to allow athletes, I had three.”

When asked how athletic trainers can slow this rash of injuries, Winkelmann offered simple advice. “Making sure people know that you can’t go full force again after taking that time off,” he explained. “Reintegrate slowly, and let the athletic trainer be involved in the process.”

Like the athletes they work with, athletic trainers and physical therapists will face a new slate of challenges in the coming months. It was no small task for them to aid COVID-19 vaccination sites and public health outfits. The very resilience often exemplified by athletes has been put on full display by those who help stars shine.

“People understand our scope of practice now, the totality of care,” said Winkelmann when asked about the versatility of his professional peers. “[We] know about policy development, policy implementation. We are the people that create the emergency action plans."

In a year when the athletes they served were on a pandemic-induced hiatus, the advocates of resiliency had to learn what they themselves were made of. Now, they can continue to build upon this and keep moving forward.

“The pandemic’s really highlighted that we know public health and primary care,” said Winkelmann. “Even when sports went away, we were good stewards within communities and I think now we have that platform for people to trust us with what we can do."