Bianca Hernandez-Knight is a Jane Austen enthusiast.

In graduate school in 2013, studying anthropology at the University of Southern California, she would spend her Saturdays taking a bus to West Hollywood to attend a local chapter of the Jane Austen Society of North America, or JASNA. She moderated the various social media pages of “Drunk Austen,” which shared memes related to the books, like Mr. Darcy’s recurring awkward lines.

But there was one activity that led her to experience Jane Austen’s world on an entirely different level.

After Hernandez-Knight, 32, originally from Bakersfield, moved to the Bay Area in 2015, she joined the local JASNA chapter. But this chapter did something her previous chapters did not: they attended Regency balls hosted by local dance societies.

Hernandez-Knight could not pass up the opportunity.

“Of course,” Hernandez-Knight said, “I'm going to say yes to a ball invitation. No lady who has read Jane Austen would say no to the invitation to the ball.”

Hernandez-Knight attending an event in the first Regency dress she made (Credit: Bianca Hernandez-Knight)

Hernandez-Knight attended her first ball with a simple white polyester prom dress she bought from Ross, the discount store, and altered it to include a sash and puffed sleeves to make it more in line with the Regency style. It was by no means the most historically accurate outfit. All the same, it led Hernandez-Knight to explore a new interest in what is called historical costuming.

Historical costuming recently gained in popularity online after the release of Netflix’s “Bridgerton,” but the hobby has been around since at least the 1960s in the form of reenactments, when centennial commemorations of the Civil War took place across the country. Since then, the hobby has expanded to include civilian events, like balls and teas, and varying degrees of immersiveness and authenticity.

Today’s hobbyists come from a variety of sources, including Jane Austen’s work, a general interest in history and period dramas. The shared interest of clothes allows for an added dimension towards each person’s passions.

The rise in popularity of historical costuming, however, has also brought forward an uncomfortable reality because the spotlight of scrutiny does not comfortably mesh with the glamorization of history.

With issues of race, equity, diversity and inclusion increasingly at the forefront, some number of costumers — people of color — have found themselves on the margins.

And on the margins is not a place they ever expected, in the 21st century, to be when dealing with the 18th or 19th centuries.

Marvin-Alonso Greer, 34, originally from Atlanta, considered himself a reenactor at first, focused on dressing authentically and participating in Civil War reenactment battles. Eventually, he began to attend invitation-only events that gave him a sense of status within the Civil War reenacting world. But he soon saw a pattern of some reenactors using hateful language that made him feel uncomfortable despite how “authentic” that language was to the time.

“There were people that I met that I liked that were concerned with authenticity but,” Greer said, “they definitely harbored white supremacy.”

The history of historical costuming

Historical costuming in its modern form began in the early 1960s when centennial celebrations of the Civil War popped up across the country. History could literally come alive. Anyone who might be interested could take part in reenacting, in front of increasingly significant crowds, some of the most significant battles of the war.

To be clear, reenacting itself was not new.

What was, was this:

Civil War reenactments in the 1960s introduced the idea of reenacting – as a hobby – with volunteers.

Civil War reenacting continues today but has expanded to include living history (Credit: Marvin-Alonso Greer)

At first, these reenactments emphasized the spectacle of skirmishes over the authenticity of the impressions.

In one notable reenactment of Bull Run in July 1961, reenactors proved so inexperienced with the weapons they were using that several suffered injuries from unsafe weapon practices.

Over time, the emphasis shifted to authenticity, giving hobbyists some authority over the time periods they depicted. Reenactors even served as extras in movies like “Glory” and “Gettysburg.”

At the same time, reenacting grew as a hobby, museums and historical sites introduced the idea of living history, a less-immersive form of reenacting where interpreters could “break the fourth wall” and interact with visitors — in character, of course.

Anneliese Meck, along with being a hobbyist, also works as a historical interpreter at a living history museum (Credit: Anneliese Meck)

Colonial Williamsburg, which had used reenactors as part of the experience since its restoration in the late 1920s, introduced living historians in 1978 who, unlike reenactors, could interact with the public. Since its founding in the early 1970s, the Association for Living History, Farm and Agricultural Museums advocated for the notable living history technique of using reproductions that historians could interact with in front of the public.

Though this idea of living history started in the museum and professional side of historical costuming, its looser standards expanded to the hobby side, which presented more opportunities to dress in a specific era’s garbs without needing to portray a specific person or even a type of person.

Hobbyists could simply be themselves, enjoying the civilian life of a time period.

With less stress on historical events and figures, time periods themselves could be at the forefront, opening up the hobby to individuals beyond the standard history buff.

Fictional works rather than specific historical events inspired annual retreats like Dickens Fair in northern California. And, notably, the Jane Austen Festival in Louisville, Kentucky, where attendees can dress, eat, and dance in ways more conducive to the era in which the author lived.

But while the standards for authenticity vary from hobbyist to hobbyist, the costs of creating historical outfits can add up. Unlike in a museum or historical site, where clothing is provided, hobbyists have a choice over the clothing they wear and in turn, the degree of authenticity.

The costs of costuming

Most clothing from the 18th and 19th centuries is made from natural fibers: linen, silk and cotton.

Those fabrics run more expensive than synthetic fibers like rayon and polyester. For beginners or those on a budget, it could make more sense to use synthetic fibers, even if those would not have been the right material for the clothes the hobbyist is recreating.

Adding to the cost is the time it can take to make a new outfit. A hobbyist’s keen eye can notice the difference in the stitches done on a sewing machine compared to stitches handsewn, although the latter choice can add days or even weeks to finish an outfit.

Some hobbyists will even take the time to paint the fabric pattern as it would have been done during the clothing's era (Credit: Samantha Bullat)

While the average cost of a dress goes down compared to the initial costs of acquiring common clothing items like chemises, bustle pads and shoes, costuming as a hobbyist can assuredly require an investment.

To be a casual hobbyist, who makes one or two dresses, costs could be under $50 through buying at thrift shops and making minor alterations.

Someone who is more into the hobby could spend around $250 for a simple dress when creating garments like corsets and hoop skirts that are meant to mix and match with other outfits and can last years.

For more intricate outfits, costs can be around $800 when taking into account the cost of those recurring items. Someone who prefers to buy ready-to-wear dresses on Etsy is looking at perhaps $400 for a Regency dress to about $900 for a Victorian gown.

Given the amount of labor and fabric costs, it only makes sense that those who can afford to spend more money and time can create more authentic clothes.

In turn, such authenticity might prompt opportunities to attend events like Jubilé Imperial, a Napoleonic reenactment event that invites costume hobbyists from around the world and requires the hobbyist to receive approval for their outfit prior to the reenactment event in September in Reiul-Malmaison, France.

Samantha Bullat and her husband Michael McCarty attended Jubilé Imperial in 2017 (Credit: Samantha Bullat)

Meanwhile, those who have limited time and resources may not be able to engage in the hobby as much as they would like or may face comments over the inaccuracies in their clothing.

But while costuming “snobs” may gatekeep over the authenticity of an outfit, the popularity of period dramas often introduces historical costuming to the general public. The latest culprit? Netflix’s “Bridgerton.”

The Shonda Rhimes-produced show takes place in Regency England and centers around high society’s glamorous courting season. Its diverse cast presented a different England in the 1820s, where Queen Charlotte is portrayed by Black actress Golda Rosheuvel and the beloved Duke of Hastings is played by René-Jean Page.

Critics and viewers praised "Bridgerton" for its diverse cast, something unusual for period dramas (Credit: Netflix)

The show debuted Christmas Day 2020 and quickly generated buzz online, from its orchestral versions of modern day pop songs like Taylor Swift’s “Wildest Dreams” to its numerous sex scenes to the Duke of Hastings’ famous “I burn for you” quote.

And the numbers don’t lie.

The show’s debut broke Netflix records, becoming the most viewed show on the platform with 82 million households watching within the first month of the show’s premiere.

But the craze surrounding “Bridgerton” did not end at the show itself.

The show’s costuming inspired others to live out their “Bridgerton” dreams and corset sales skyrocketed following the show’s debut. Other common items from the show like long gloves and pearled headbands also rose in sales.

Across the social media platform TikTok, women shared their purchases, with one user showing off a popular SheIn green corset with the caption “Bridgerton made me buy it.”

Some would show themselves making Regency dresses themselves.

It was not long until historical costumers jumped in with their knowledge of the era’s clothing and how these fans can get the full “Bridgerton” experience, complete with balls to wear their new Regency attire.

But while “Bridgerton” offers an avenue for the historical costuming hobby to attract fans whose backgrounds are as diverse as the show, the unexpected turn was — is — the experience some costumers of color had from the hobby.

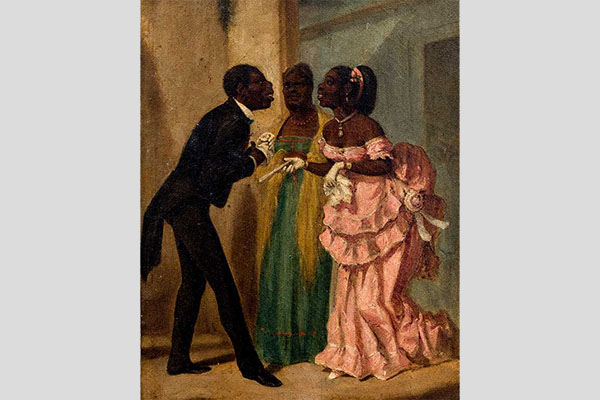

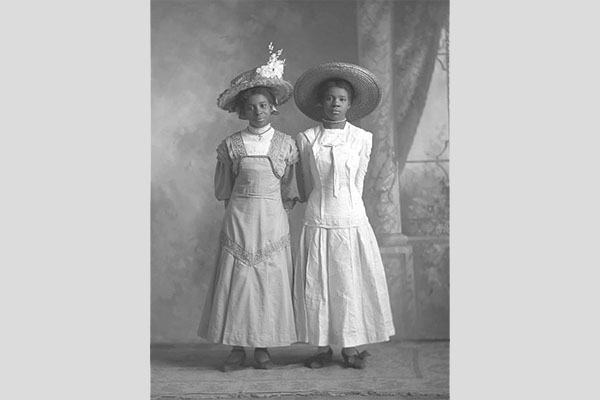

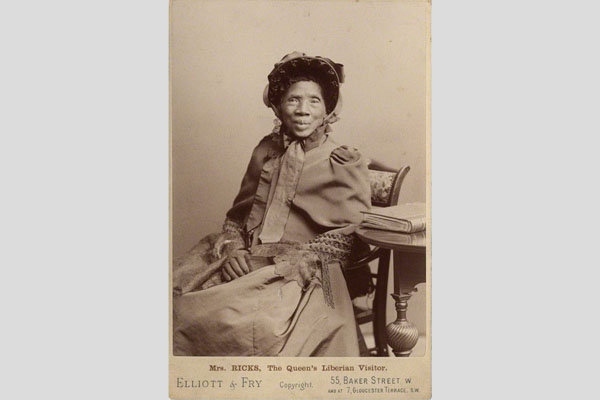

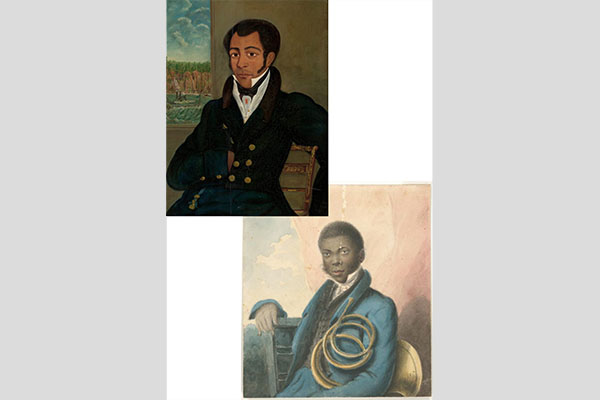

The whiteness of historical costuming

Statistically, the demographics of reenactors and living historians tend to be predominantly white. That can impact the way history is depicted, despite many of these hobbyists striving for some level of authenticity.

Black Civil War reenactors only make up a small number of reenactors in the hobby. For context, the number of Black Union soldiers during the actual Civil War was in the hundreds of thousands. Meanwhile 72% of museum staff, including interpreters, are white, and historical sites in the past, like Mount Vernon, faced criticism over their erasure of slavery and what an enslaved person’s life was like.

A quick search of popular hashtags related to the hobby like #historicalcostuming and #GeorgianJanuary shows an image for what a typical costumer looks like: white, female and financially secure enough to buy materials like silk in order to create authentic clothing.

The hobby’s whiteness, both in demographics and in the history portrayed, can — unintentionally or otherwise — foster a space that alienates people of color.

Countless hobbyists of color said they have faced everything from microaggressions to outright displays of racism.

Samantha Bullat, 29, of Huntington Beach, Calif., chooses a color-blind approach for her costuming, focusing more on what women wore in the era she is depicting rather than what someone of her ethnic background — someone of mixed race and Asian ancestry — would specifically wear. Despite this approach, Bullat faced comments in the past over her race.

“A reenacting friend asked me if I had ever considered portraying a Chinese woman during the Civil War,” Bullat wrote in a January 2020 blog post entitled “Who Am I?” It went on: “I shouldn't have to justify my existence to take part in a hobby.”

Costumers of Color push for "vintage styles, not vintage values"

Naomi Glazer

Vivian Lee

Asha Taylor

Anneliese Meck

Others faced more explicit comments.

Naomi Glazer, 24, of Gainesville, Fla., has participated in reenactments since she was a child. At age 10, she attended her first ball with her mother. When she arrived, a couple came up to Glazer and her mother, asking what they were doing there.

“They told me, ‘Black people didn’t go to a ball back then,’” Glazer said. “OK, but it’s 2009. Why am I not allowed to go here? That was so hard to hear.”

Glazer (right) reenacting as a young girl (Credit: Naomi Glazer)

The moment still sticks. But Glazer continues to participate in civilian Civil War reenactments. While Glazer says she has not heard similar comments in recent years, she had friends share their more recent experiences with similar types of comments.

“It can be super-difficult to deal with and it really knocks your confidence down,” Glazer said.

At one invitation-only event, Greer was the only Black man participating — where he portrayed an enslaved person. At a tavern set up for the event, the other reenactors sang minstrel songs and debated secession. One referred to Greer as the n-word when telling the bartender to get Greer a drink.

Though this was all done during the reenactment event where everyone was portraying a Civil War era character, at the very same tavern event, some of the reenactors asked who Greer really was and about his background — as opposed to his character’s background.

Greer says the event was not an isolated incident.

On different occasions, he witnessed reenacting friends make racist, chauvinistic or homophobic comments.

“It just was inappropriate and hate-filled,” he said, adding, “I wish that I had had the voice to speak up at that time.”

Greer continues to participate in Civil War events, but now as a living historian who can provide additional context and historical facts (Credit: Marvin Alonso-Greer)

Greer ultimately left reenactment to instead do living history, where he can provide modern context to events and explain why certain actions are looked down upon today, both of which reenactors do not do as it requires stepping out of the immersiveness reenactors strive for.

“I have no problem with someone doing a Confederate impression if they're willing to talk about the actual history,” Greer said.

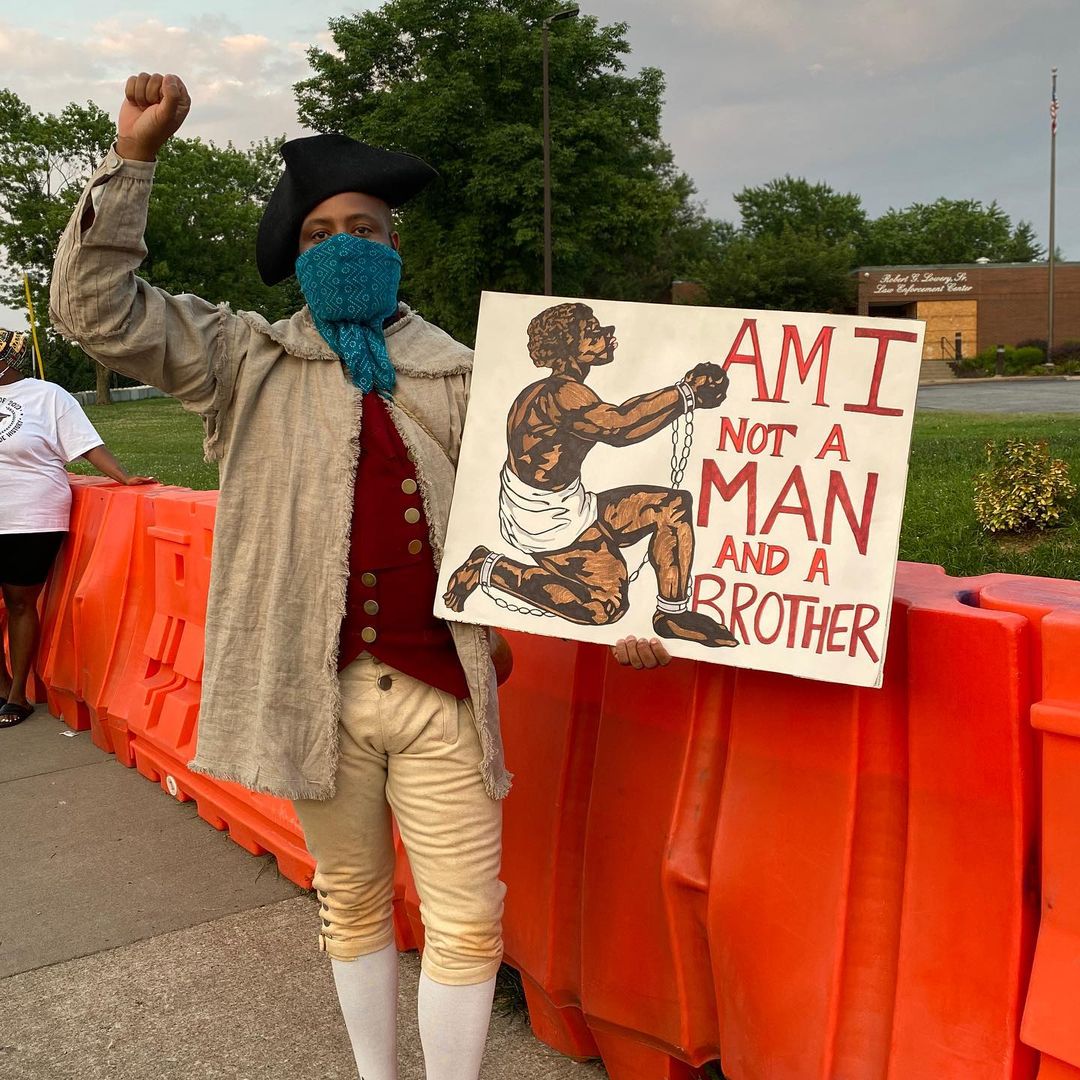

The question of context is one that grew in importance especially in the past year and has transcended the historical costuming hobby.

When the aftermath of George Floyd’s killing led the general public to reexamine what has been included and what has been omitted in history, a significant number of costumers sought to reexamine their hobby, too and, along with it, what messages their clothing gives.

“In the past year, there has been a push to acknowledge the fact that these pretty clothes only existed because there were people who were being subjugated,” Emily Doherty, 31 from Mount Desert Island, Maine, a white woman, said.

That acknowledgement is not always comfortable, especially when there might legitimately be no intent to be insensitive or the focus is solely on the clothing and not the history.

Bullat was initially introduced into historical costuming though Civil War reenactment events as a teenager in Huntington Beach. However, she has since limited dressing in the era’s clothing to solely educational purposes. This came after experiencing discomfort at a conference on the material culture of the 1860s in South Carolina, where she joined others in wearing Antebellum clothing.

“Something about being there and being dressed up in that clothing stuck with me in terms of what message that is sending to people,” Bullat said. “Do they think that I want to be this Southern belle and perpetuate that kind of romanticized view of the South? That's not my intention, but I can't control what other people might perceive.”

Despite focusing solely on the fashion, Bullat now limits wearing Civil War-era clothing like this ballgown (Credit: Samantha Bullat)

While there is no hard data breaking down the demographics of historical costumers as hobbyists nor the number of incidents pertaining to discrimination and microaggressions, costumers of color say there remains work to be done to ensure that the hobby is inclusive to others. And with COVID-19 cancelling in-person events, it remains to be seen whether the blunt conversation from this past year will translate offline.

Many costumers can point to instances where they were the only person of color at an event, making them feel alone in their experiences if any racially insensitive comments or behavior arose and no one else spoke up. These costumers felt the responsibility fall on them to call people out or to educate. And it isn’t always something they feel they can do.

Hernandez-Knight quickly discovered the harsh reality of historical costuming and race at one of the first costuming events she attended after the Austen ball. She encountered several people using the outdated term “orientalism” as a theme for their clothing and decorations, without even an acknowledgement over the problematic nature of the term.

Still new to the hobby, Hernandez-Knight questioned her discomfort since it seemed others at the event were OK with the theme.

“It’s one of those things where you think, ‘Am I just not meant for this space? Maybe I should just shut up and leave,’” Hernandez-Knight said. “Do I want to waste my breath on someone who is just going to double down and not listen or do I just want to go somewhere else?”

Hernandez-Knight, who identifies as Latinx, now feels more comfortable having tough discussions on race with other costumers willing to listen. She also finds that with online spaces, it’s easier as a person of color to find communities that are inclusive and welcoming.

Paving their own path

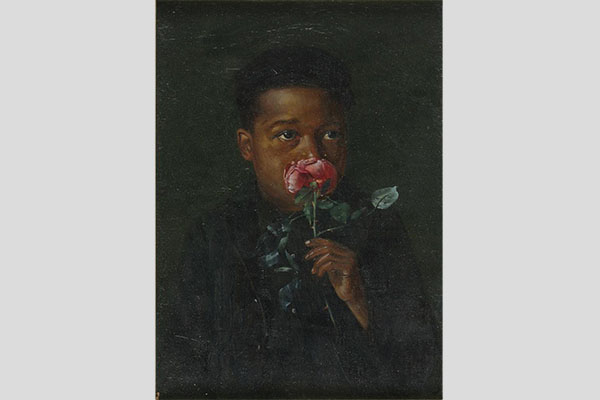

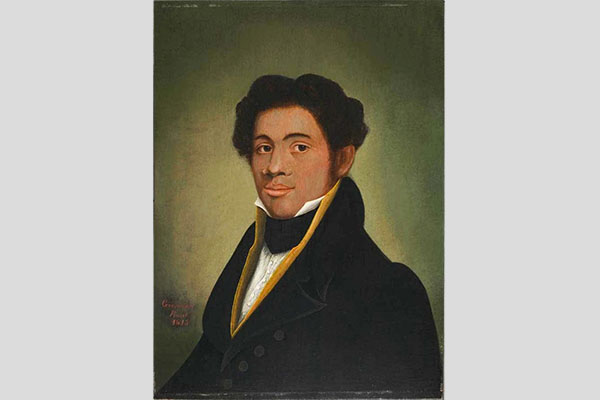

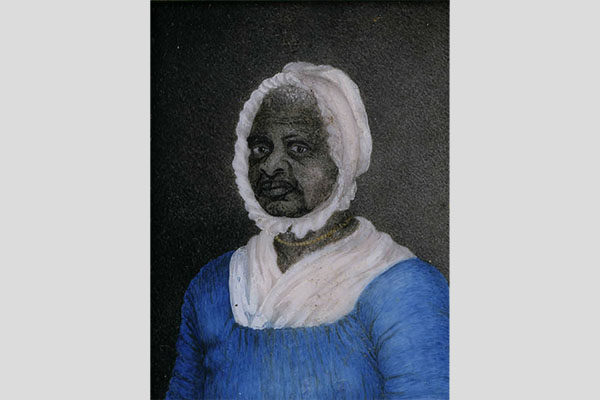

Despite gatekeepers, several costumers of color found ways to make the hobby their own and fight against issues in the hobby. Click each photo to learn more.

Now more experienced, Hernandez-Knight advocates for inclusivity in the hobby (Credit: Bianca Hernandez-Knight)

But as the pandemic draws to a close and in-person costuming events return, Hernandez-Knight emphasizes the importance and urgency of creating an inclusive hobby where newcomers don’t have the same dilemmas she and other costumers of color faced at events.

“You’re going to have things like Bridgerton and other historical-adjacent things that people are going to get excited about,” Hernandez-Knight said. “People really need to think about how the communities that are going to be coming are going to be more diverse and they're going to want inclusion.”