On Dec. 4, 2017, Lisa Greenbaum and her son stepped out onto their porch to see the horizon in flames. Greenbaum was no stranger to wildfires, but this was something different. She was a five-year resident of a quiet community in Ventura County, California, and the flames she was looking at that night were from the Thomas Fire. All in all, the fire would end up burning through over a thousand structures in its way and causing upwards of $2 billion in damages and 23 deaths. Greenbaum and her son would survive, and so would her home; but a year and a half later, she still gets anxious when she hears the wind blowing at night.

Greenbaum is grateful for the help that arrived from all over the state and the country during the fire and in its aftermath, and is reverent of the firefighters who put their lives at risk for her and her neighbors. But, there was a problem.

“I think that the fire became out of control and overwhelming very quickly,” said Greenbaum. “It was pretty evident that the emergency responders were completely overwhelmed.”

Greenbaum echoed a familiar problem. During fire season, which more and more appears to span almost the entire year in California, fire departments struggle to assemble sufficient resources necessary to combat the fires that rage, sometimes simultaneously, across the state. A public records request for staffing data for the LA County Fire Department filed by Annenberg Media is still pending at the time of publishing, but analysis from an October 2018 LA Times article shows that overtime costs at the department surged a staggering 36% in five years. Overtime cost analysis serves as a good proxy in the absence of more specific personnel and staffing data, since employers often use overtime to compensate for staffing shortages. According to the LA Times report, in 2017, roughly 650 fire department workers earned over $100,000 in overtime, while two dozen earned over $200,000 in overtime. The high overtime rate is indicative of a systemic and growing problem facing county firefighters.

Malibu’s Fire Station 99 sits on the Pacific Coast Highway, and on a warm summer day in July 2019, three firefighters sat comfortably at a table, happy that three reporters walked in and “brought the vibe up.” Outside, a sign featuring Smokey the Bear amiably read: “Fire Danger Low Today!”

The firefighters were working a schedule that would seem inconceivable to anyone, and alarming considering the type of work firefighters are tasked with doing. Bob George, a fire engineer and 14-year LA County Fire Department veteran, said “Normally, you do ten 24-hour shifts a month. Right now, most firefighter, engineer and captain ranks are having to work a lot more… in some cases, five on, one off, with no end in sight,” he said. In other words, instead of working ten days of 24-hour shifts in a month, firefighters at Station 99 are working 25 days of 24-hour shifts a month, taking only one day off between each block of five consecutive 24-hour shifts.

“Obviously, you’re going to have the repercussions of that,” said Robert Sales, fire captain and 21-year LA County Fire Department veteran. “It creates a tremendous amount of stress on families and loved ones… even the guilt of missing all your kids’ basketball games. It’s crushing.”

“It’s one thing to be on a fire, the Woolsey incident," Sales continued. "That is what we signed up for and obviously, we want to be of service. But to have that 24-7, 365 days a year is completely unsustainable.”

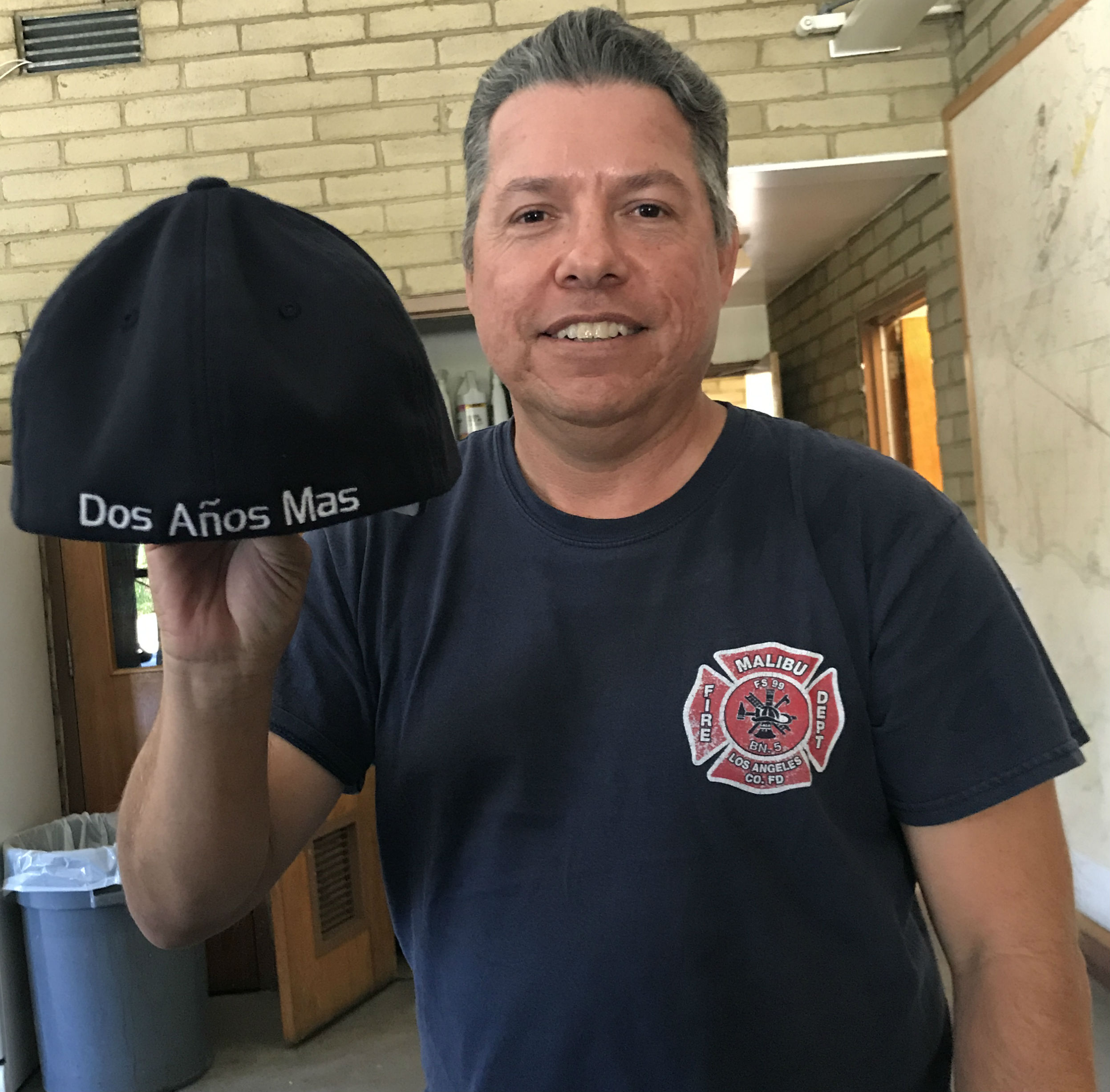

Firefighter Victor Sanchez, who has been with the LA County Fire Department for 28 years, will soon retire. He smiled brightly as he pointed at his baseball hat. The words on the back read: “Dos Años Mas” – Spanish for “Two More Years.”

***

On Nov. 8, 2018, a fire ignited in an industrial complex owned by the Boeing Company in the Santa Susana Mountains, close to the border of Los Angeles and Ventura counties. The Woolsey Fire would end up burning for almost two weeks, and during that time, it would destroy 1,643 structures, cause three deaths, and prompt the evacuation of almost 300,000 people.

Jennifer Briggs and her husband Steve, residents of a neighborhood called Malibu West, had lingered even after evacuation orders went out. They had been skeptical – they thought it was unlikely that the fire they had been hearing about would reach them. Then, a friend who had once worked with the fire department called. He warned her that if there was smoke over her house, it was not a matter of if the fire would reach them; it was a matter of when. The Briggs left, and by the time they had reached the corner grocery store, there were flames coming over the hill.

The Briggs returned to Malibu West six weeks later to find their home covered in ash. Her family had been lucky. Of the 250 homes in the neighborhood, 27 had burned to the ground, according to a source at the Malibu West Beach Club. The ones that remained standing had been saved by a group of “guys," as Briggs described them, called the Malibu West Fire Brigade.

Briggs said that the group had trained with a retired fire chief and bought their own fire equipment. According to a Daily News article from the time, members of the amateur group had posted up on a hilltop and ran from one house to another, dousing each with water.

“That’s the only reason [most of the houses] are still there,” said Briggs.

Briggs said she watched as a fleet of 16 fire engines made a U-turn as flames came over the hill, and then parked at Zuma beach. She was pointing at her best friend’s house, burning down.

“I think they were really overwhelmed, under-staffed, under-equipped. I just think they were in over their heads,” said Briggs, speaking of county firefighters.

Briggs said that today, her neighborhood resembles a warzone. There is construction everywhere. And when it rains, there are floods, and mud comes flying down the hill. And like Greenbaum in Ventura County, she gets nervous, every time the wind blows.

Data obtained from the Insurance Information Institute, an insurance trade institute supported by major insurance companies, shows that the number of acres burned in wildfires has been rising steadily since the 1980s. In general, trends show that fires in recent years have been burning longer and destroying more land. For the LA County Fire Department, and other departments throughout the country, keeping up with the increasing demands for fire control services is a challenge.

“I’ve been on since 1992, and we have been getting more intense fires throughout my career, so it definitely affects our job big time,” said firefighter Sanchez of Station 99. “You can’t hire enough firefighters to handle the fires that are going on, it’s just not possible. They couldn’t afford it.”

With the LA County Fire Department struggling to fill its staffing needs even on typical days without large brush fires, residents who live in fire-prone areas are looking to alternative means of protection. Some, like Briggs, rely on volunteer firefighters, people who ignore evacuation orders to protect their neighborhoods. Others, like, Kim Kardashian and Kanye West, use private firefighters contracted through insurance. After the Woolsey Fire, Kim Kardashian appeared on “The Ellen Show,” and described the experience of having their house saved by private firefighters as “being blessed.” After the firefighters had managed to defend the Wests’ home, she requested that they save surrounding homes in their neighborhood as well.

Janet Ruiz, a spokesperson for the Insurance Information Institute said that private fire services, as she called them, “work really well.”

“[Private fire services] are required to check in with what’s called incident command… either CAL FIRE (California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection) or the county fire department or the local fire department. Fire services are required to check in and let them know they are there and what they are doing,” said Ruiz.

Firefighters at Station 99, who said they had no interaction with private firefighters during the Woolsey Fire, had concerns.

“We’ve got no communication, no concept of your training, your equipment, we don’t know what you’re going to do,” said Capt. Sales, referring to private firefighters. “You’re a wildcard. Are you going to get in the way? Are you going to block the road? Are you going to be a rescue hazard? Are you going to be a help? Are you going to be a hindrance? We haven’t even talked to you. I have no idea who you are.”

Sanchez added that unlike public responders, private firefighters are not sworn citizens, which means that they are not held to the same standards of accountability as public firefighters.

Nov. 8, 2018, the day the Woolsey Fire started, was a bad day for California. Two other wildfires ignited on the same day, and one of them, up north, would end up wiping out an entire community. Emergency response in California was already spread thin; that day it was spread even thinner.

Sanchez and Capt. Sales were among six firefighters on duty at Station 99 that day.

“I know the state of California was taxed to the limit,” said Sanchez. “We didn’t have enough air resources. People were talking about, how come we don’t have any helicopters? Well, because they were up north. There’s not enough resources to go around for everybody, that’s the bottom line.”

Looking back on the Woolsey Fire, Capt. Sales said that he felt a sense of loss.

“It really bugged me, you know, just driving around here,” he said, his normally steady voice shaking for a moment. “We lost a lot of homes, especially if you go above Zuma. But also in our district…it was definitely a strong sense of loss, disappointment. As time went on, it got better, and you were able to focus in on, hey, we didn’t lose our shopping center or schools, all the infrastructure. It’s worse in Paradise (the town wiped out by the Camp Fire). It’s not even a community any more. There’s nothing left. We did way better than that, and there are a ton of homes that didn’t burn. So, over time, it feels better. But you know… nobody wants that.”

Even so, Sales said that he has the best job in the world.

“You could not do better, arguably, in terms of a mainstream job,” he said. “And I’d tell that to any young man or woman. If you think you want to do this, you definitely want to do this.”

Greenbaum, now 55, still lives in her quiet community in Ventura County. She said that after the fire, she went to a therapist to do some EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) work, designed to help patients cope with post-traumatic stress disorder. Her therapist had lost her home in the 2008 Tea Fire, and reminded Greenbaum that, despite her loss, she was okay.

Greenbaum is hopeful for the future. She recalled reading that the Ventura County Fire department had acquired new equipment and resources. She remembered how she would sometimes break down crying when she saw firefighters in town in the aftermath of the Thomas Fire, and continues to be grateful to them.

“I hope we’re paying them well enough,” she said, “and that they continue to remain dedicated to serving everybody.”