A sleepy voice came on the phone at 9 on a Friday morning. Carla Foreman-Maslin had spent the evening with her children and grandchildren. Even though it was the middle of the Coronavirus pandemic, she had a lot to celebrate this weekend. It was her anniversary with her husband, her son and grandmother’s birthdays and her grandchildren were graduating.

Carla’s sleepy voice quickly grew excited as she talked proudly about her family and their accomplishments. Especially when she got into the life of her late father, Bob Foreman.

“He was very charismatic, he knew how to talk to people,” Carla said of her father. “So when he got out of the service, my great grandmother got him involved in the Indian community because she knew he cared about people.”

Despite Bob Foreman becoming the first elected tribal chairman for the Redding Rancheria in 1985, he and his family were kicked out of the tribe less than 20 years later. Though what the Foreman family went through–a process known as tribal disenrollment–is not uncommon, the act of having to disinter family members for DNA testing is one of the most extreme measures any family has been forced to do to prevent it.

Carla’s great grandmother, Virginia Timmons, lived on the Redding Rancheria. She was one of 17 Native people on the rancheria when the federal government disbanded it in 1959–an act during the Indian termination policy that aimed to force Native people to assimilate into American society. The policy saw thousands relocated, children forced into boarding schools away from their families, reduced civil rights and acts of violence against the country’s first people.

After leaving the service, Bob worked construction until his grandmother got him involved in the Indian community, Carla said. He advocated for health in the community as a founding member of the California Indian Rural Health Board and started three clinics in three counties during the 1960s.

Though Virginia didn't live to see it, the Redding Rancheria was recognized as a tribe following a four-year lawsuit filed by Tillie Hardwick in 1979. The class action lawsuit fought to restore the status of 17 rancherias in California. Bob became the first tribal chairperson for the Redding Rancheria.

Bob’s efforts saw a growth in healthcare, dental care and eventually a local office for The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); which Carla’s sister helped to establish. After the tribe was reinstated, he worked to have the clinic under the tribe. And established it as a successful clinic that served all local Indians. Later, the tribe's casino, Win-River, was established.

The Foreman family had been involved in the tribe since the beginning. It was a shock when they received a letter that would change everything.

“We got a letter from the enrollment committee,” Carla said. “It said there was a question about the Foreman family. It was raised by an elder that we never got to even talk to.”

The tribe’s enrollment committee, which is in charge of deciding who does and does not belong in the tribe, claimed to receive a letter–a sort of deathbed confession.

The Foremans were informed that Dorothy Dominguez, an elder dying of cancer, wrote in a letter that Virgina Timmons never had children. Meaning the enrollment of Carla’s since-deceased grandmother, Lorena, once a member of the tribal council, was challenged. And therefore, Lorena’s children (Bob and his three siblings) and the following three generations were questioned about the legitimacy of their enrollment.

Was Lorena truly the daughter of Virginia Timmons? It was the million-dollar question–literally. Or, more like the $2.7 million question.

In 2002, when the lineage of the Foreman family was being investigated, the tribe’s casino revenue put about $3,000 in the pocket of every tribal member of the Redding Rancheria in the form of checks known as per capita payments.

“If the Foremans have produced any evidence other than the circumstances to suggest this is about money, I’d like to know what it is,” David Rapport, a lawyer for the tribe, told the Los Angeles Times in 2004.

The inquisition went on for two years. In a file the tribe had on Lorena, a birth certificate, baptismal certificate, or definitive proof of her maternity could not be found.

“They couldn't get a birth certificate because they couldn't get in a hospital,” Carla said.

Lorena was born in 1916, eight years before the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 passed.

“Since 1924, the federal government passed a law that said every Indian born in the United States is a citizen of the United States,” David Wilkins, a professor of American Indian studies at the University of Minnesota, said. Wilkins is the lead researcher on tribal disenrollment in the country.

According to Carla and many other scholars, it wasn’t uncommon for a Native American to not have a certificate of birth or proof of baptism during that time. Though a delayed birth certificate was issued to Lorena and was found following her death, the tribe did not accept it.

In September of 2003, the tribe held an evidentiary hearing and later an anonymous vote by all adult members of the tribe, the LA Times reported.

The Foremans presented family records, witnesses, testimony from two anthropologists specializing in California Native Americans and proof that their family members' names were listed as related on the 1928 California Judgement roll (a state census that recorded all Native people).

“That proved that they were mother and daughter,” Carla said. “We had other historical documents. We had our family Bible, which my great grandmother Virginia started and she has it all written down. We gave them everything. They just kept going.”

The family hired an attorney to help them organize the mountain of evidence to prepare their defense–but not in the kind of court most people think of. Native American tribes are sovereign.

In the 1978 Supreme Court case of Santa Clara vs. Martinez, the court set a precedent that leaves many tribal disenrollees without hope of legally fighting their way back into their tribe.

“The Supreme Court in a ruling written by Thurgood Marshall, said tribal membership ultimately is a decision left up to the tribe,” Wilkins said. “After that decision, I think tribes became emboldened.”

To the tribal council, the mountain of evidence the Foremans put together could as easily been a grain of sand. Like many others in disenrollment limbo, the Foremans were not allowed to vote with the rest of the tribe on their disenrollment.

“We had so much documentation. It was crazy. So it got down to them requiring DNA,” Carla said. “You're scratching your head saying, ‘What does that mean?’ Both my great grandmother and grandmother are dead. Buried.”

According to Carla, when the family met with the enrollment committee, one woman told them to do the unimaginable.

“An elderly enrollment person, who knew my family, her kids grew up with us–she says to my aunt, ‘Dig her up. She’s nothing but a bag of bones,’” Carla said as her voice cracked over the phone. “...about my grandma.”

Disinterring the Foreman matriarchs was a last resort. So much of the family had lost their livelihood, tribal jobs, voting rights, and identity. Generations to come faced losing more, like never knowing what it was like to be an enrolled member.

“My dad was getting sick from it. We had to make that decision,” Carla said.

The family contacted a world renowned DNA scientist, Carla said, known for helping to identify victims of the 9/11 terror attacks at the World Trade Center.

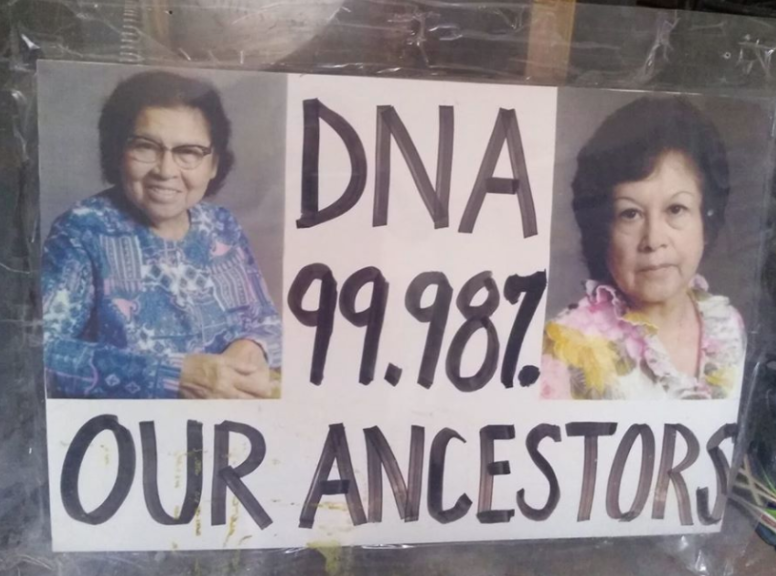

Virgina Timmons, the family’s matriarch whose belonging to the tribe was undisputed, was the first to be exhumed. She had been buried so long that they were unsure if a DNA sample could be obtained, but a bone sample yielded some. Virginia’s DNA was tested against Carla’s aunt. The results came back.

99.9% positive.

“That was a match–she, my aunt, was the granddaughter to my great grandmother, Virginia,” Carla said. “But they didn't accept that. They wanted us to exhume my grandmother now.”

Virginia and Lorena’s DNA were tested against each other through both mitochondrial and genomic DNA tests.

99.9% positive.

The DNA results were presented to the tribe. The Foremans thought it was bulletproof. But after two years of fighting, the family was notified that they would officially be disenrolled following a vote from the general tribe.

“That's how grotesque this gets. You have people who are forced either be disenrolled or to unearth their ancestor, take a DNA test, and still be disenrolled,” Gabe Galanda, managing lawyer at indigenous rights firm Galanda and Broadman, said.

Every generation of the Foreman family had served on the tribe’s council and committees. Even during the disenrollment process, some members were serving.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs, which nowadays rarely gets involved in cases of disenrollment (though, according to Wilkins, historically they meddled a lot), wrote a letter in support of the family to the tribe and tribal chair Tracy Edwards. The letter–a rare bit of support from the federal government and glimmer of hope for disenrollees–still wasn’t enough.

“They knew,” Carla said. “They knew that this was what they were going to do all along. They put us through this terrible ordeal and still just voted us out. It's just that they didn't expect us to bring as much information as we did.”

The legal term for the precedent the tribe used to kick out the Foremans without any checks or balances from the U.S. federal government is known as sovereign immunity.

“There was a hurdle at every single turn, but in the end, they knew they had sovereign immunity and they knew they were going to use it,” she said.

As for the letter that led to the fall of the Foremans, Carla says the handwriting suggests it’s a fraud written by a much younger woman: for example, she believes the bubbles that sit on top of the letters “I” in the letter are a clear indication that it wasn’t written by an elderly woman on her deathbed. To Carla, this proves a conspiracy to remove the Foreman family.

“We were a large family within the tribe. And at that time, there was also the other factor: the tribal members started wanting more money, the per capita,” Carla said.

Carla’s family had plans to diversify the tribe’s revenue and just before their disenrollment, another tribe member’s economic ventures were not panning out. With the 75 members of the Foreman family kicked out of the tribe, the remaining members would stand to see an extra $1,200 in their monthly checks.

In a world governed by money and with no legal options, the Foremans have had to move on from their tribe in the 16 years since their disenrollment. But in a perfect world, Carla would like to see tribes have their own intertribal legal system.

The time was now 10:30 a.m. when Carla’s voice shook with even more sadness. Earlier, the smile on her face as she talked about her dad and family was almost audible. But now the smile was long gone.

“I do cry a lot. You look at your kids and your grandkids and you think–this is who you are. Don't ever forget who you come from,” she said.

As much as she hopes her tribe’s council will one day reinstate the Foreman family, Carla doesn’t believe it will be anytime soon.

“I was hoping to see justice for my dad because he had done so much for the Indian people. To me, it almost feels like he was slowly murdered,” she said.

Since the reinstatement of Redding Rancheria in the 1980s, dozens of their people have been disenrolled.

The tribes discussed in this piece did not respond to requests for comment on their disenrollment policies. The Coronavirus pandemic prevented in-person attempts for comment.

The last known comment Redding Rancheria has made on the issue to the media was in a 2004 Los Angeles Times article. One of the last known comments from the Pechanga tribe was to KNBC in 2007. Santa Rosa has not made any recent public comments available online.