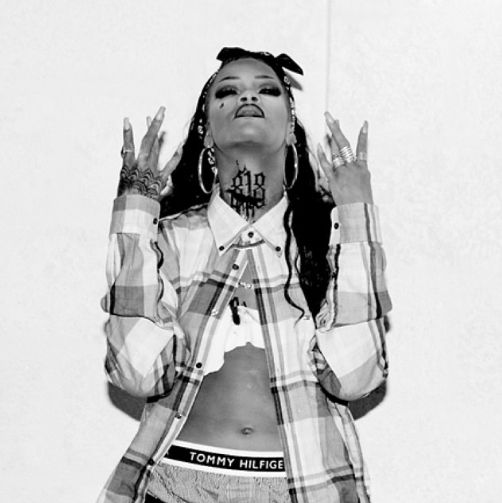

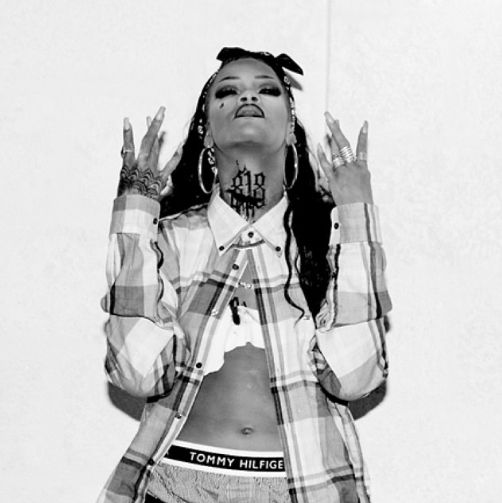

Rihanna's chola Halloween costume in 2013.

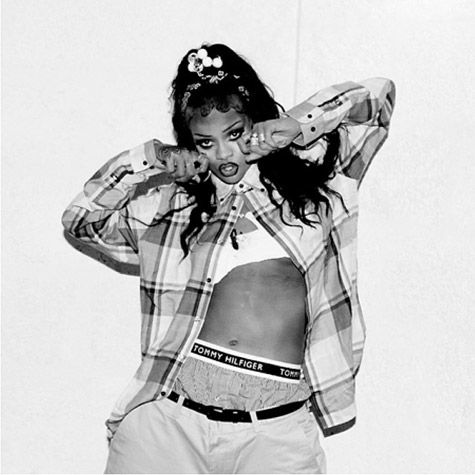

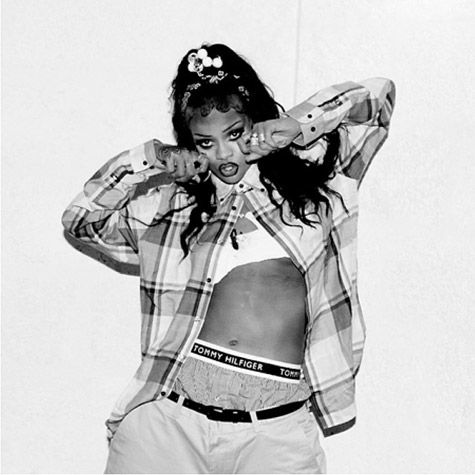

Rihanna's chola Halloween costume in 2013.

W hen someone utters the word “cholo,” what comes to mind? Most often it’s a pair of baggy Dickies khakis, oversized flannels buttoned up to the top accessorized with big hoops, dark lip liner, thick, black eyeliner and tattoos. Maybe it’s the image of an electric green Impala cruising around East Los Angeles. Perhaps the hairs on the back of your neck stand up at the immediate thought of gangs, street violence and riots.

Even if you weren’t an 80s baby growing up in LA, chances are that you’ve seen or felt the presence of cholo culture in some way. Its iconic style has made its way into music videos, viral social media posts of the “who’s who” of Hollywood, and even to New York Fashion Week.

Who could forget when Gwen Stefani traded in her “Hollaback girl” image for a crisp flannel, dark lipliner and winged eyeliner that could cut through the souls of every bad boy and toxic ex in 2005? Rihanna broke the internet in 2013 when she posted her Halloween costume on Instagram: a zombie chola complete with a teardrop below her eye. Plus, YG’s summer hit “Go Loko” blasted through the air around the world paying homage to his love for cholo culture here in LA in 2019.

There’s no denying that the word “cholo” brings up countless, striking images. For many of us, it is fused into our personal lives, whether it’s our attachment to our favorite Netflix characters like Spooky from “On My Block,” playing Grand Theft Auto with the neighborhood kids or wearing an Instagrammable streetwear fit. However, beyond its effortlessly cool exterior, the word has a rich history. It is a story and culture that speaks to the pride, resistance and empowerment of many Mexican-Americans. Even today, Mexican-Americans are embracing the cholo spirit as they are taking the term—and its cultural baggage—and reinventing it for a new era. However, one thing isn’t going away...cholo activism. So, strap in and let’s go for a ride.

Popular culture has assigned an assortment of words to describe Mexican-Americans, such as “Latinx,” “Hispanics,” “Chicanos” and, of course, “cholo.” Some words embrace the pride of Mexican-American culture, some come from dark historical moments in the United States and others are just dead wrong.

Sometimes words are hard. Here are all the words you need to know.

Bucket: a car or vehicle of poor condition, also known as a hooptie

Candy: clear paint with translucent pigment used by car artists

Candy shop: a place where car artists paint and customize cars

Cholo(a): a person belonging to a Mexican-American urban subculture popularized in Southern California

Chicano(a): a person of indigenious descent in the United States; a Mexican-American subculture often associated with pride in culture and political activism

Chicanx: the gender-neutral or nonbinary alternative to Chicano(a)

Hispanic: related to Spain or Spanish-speaking countries; a Spanish-speaking person living in the U.S., especially one of Latin American descent

Latino(a): a person of Latin American origin or descent

Latinx: the gender-neutral or nonbinary alternative to Latino(a)

Lowrider: a customized car or vehicle with a lowered body

Machismo: a subculture surrounding the exaggeration of pride in masculinity and manliness; toxic masculinity within Latin American culture

Pachuco: a subculture of Chicanos and Mexican-Americans, associated with zoot suits, street gangs, nightlife, and flamboyant styles coined in the 1940s

Zoot suit: a men's suit with high-waisted, wide-legged, tight-cuffed, pegged trousers, and a long coat with wide lapels and wide padded shoulders popularized in the 1940s by Latinos and African Americans

During WWII, the government enforced restrictions against the use of various garment materials, such as wool. However, Mexican-Americans still proudly wore their suits, which was perceived as unpatriotic.

“It was a stance against the status quo,” says Yolanda Alaniz, a Chicana writer and activist. “It was a rebellion.”

As droves of US servicemen, sailors, police officers and the like lashed out against brown and black people, Mexican-Americans used everything like hair, makeup and clothing as a form of blatant cultural identity.

During the summer of 1943, tensions were at an all-time high. Things significantly shifted when a group of sailors marched through downtown LA. With clubs and weaponry in hand, they attacked those wearing the infamous zoot suits.

This ignited the Zoot Suit Riots. Servicemen and police officers lashed out against Mexican-Americans and other people of color stripping away their suits leaving them bloodied and bruised on the streets.

This clash would become an unforgettable historical moment.

Wearing those clothes was a statement that said, “Accept me as who I am and if you don’t fuck you,” says Alaniz.

Fashion can be a powerful thing.

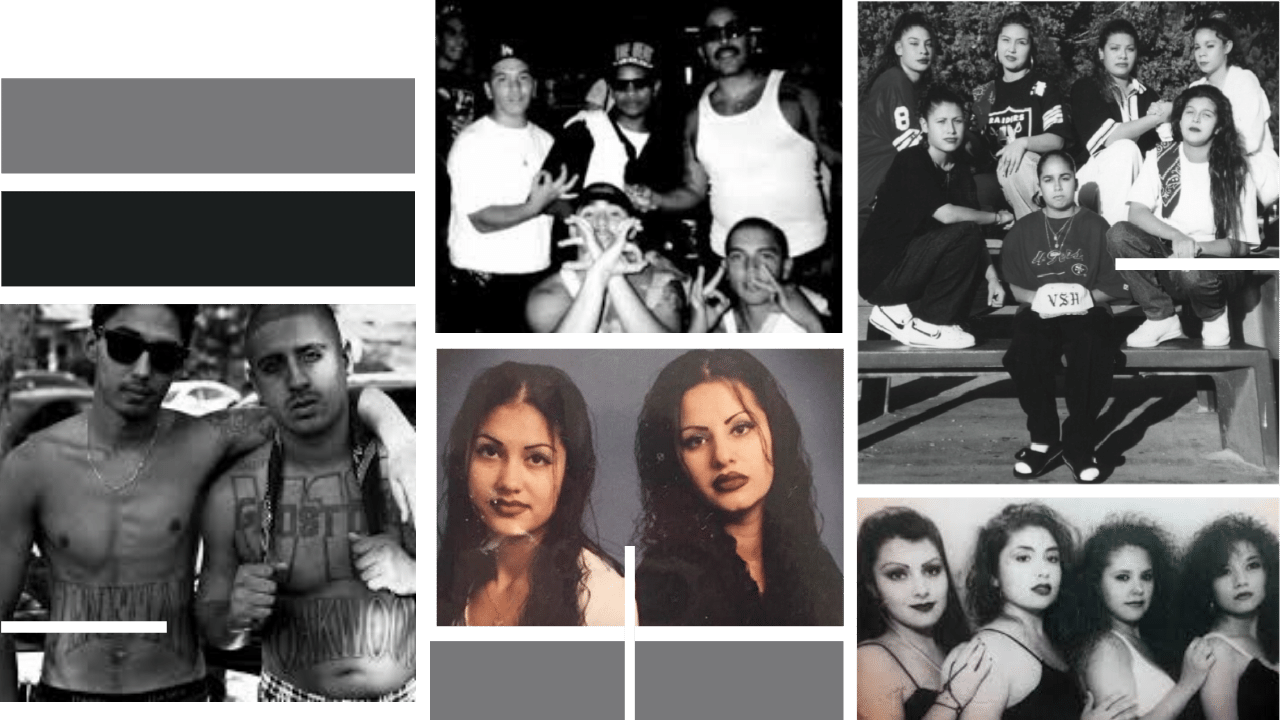

Take a look at how cholo fashion has evolved throughout history.

Adapted from African-American fashion trends popularized in jazz clubs in Harlem, Detroit and Chicago, zoot suits were worn by many minorities including Mexican-Americans. Zoot suits were known for their wide lapels, shoulder pads and pegged legs. However, they would become a symbol of resistance during the Zoot Suit Riots.

Cholo fashion made its way to the spotlight in American culture. Instead of zoot suits, oversized khakis, creased jeans and plaid shirts over white tanks became the signature look. In addition, the iconic chola beauty look was born - complete with pointed eyebrows, darkly lined lips and baby hair.

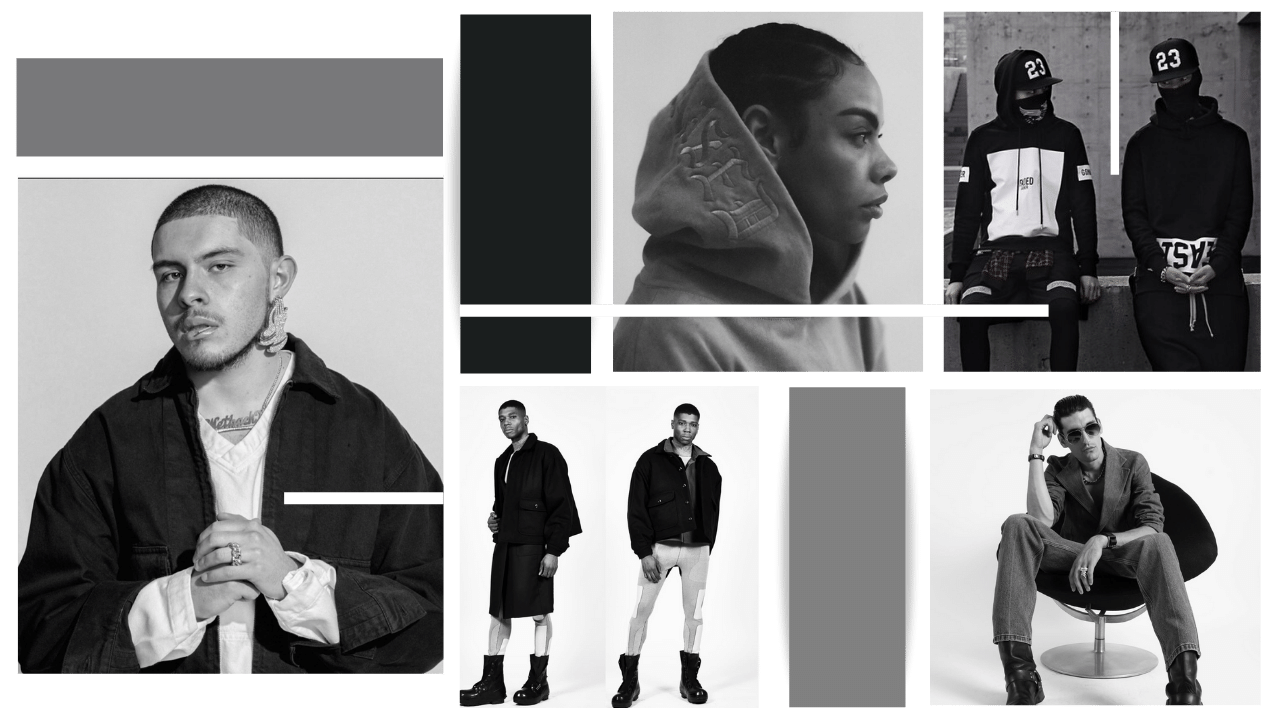

Cholo fashion has influenced modern streetwear from oversized jackets to Dickies and Chuck Taylor's. It has impacted high fashion runways and been worn by celebrities and influencers.

Pause---we can’t talk cholos or fashion without talking about Willy Chavarria.

Chavarria is an acclaimed fashion designer. Starting out in the shipping department at Joe Boxer Corp. in the 90’s, he worked his way up to being a part of the design team. From there, he eventually began designing for Ralph Lauren. It wasn’t until 2010 that he opened his own shop in NYC and in 2016 started the WILLY CHAVARRIA line.

His label is known for its oversized and cropped design, inspired by his deep affanity and admiration for cholo culture.

“My respect for Cholo culture in the United States traces back to the pachuco which emerged from the Mexican American youth in Texas and California as an expression of style and music,” Chavarria says. “It was a way in which Brown people defined themselves as being beautiful under the arm of White oppression.”

Chavarria has observed cholo style’s significant influence on fashion, especially through skate culture. However, it is mostly reserved to the hoods in which Brown people live.

“The look defined by cholos is incredibly elegant and sincere to me,” he says. “It is not an expensive look, but it is incredibly graceful and strong.”

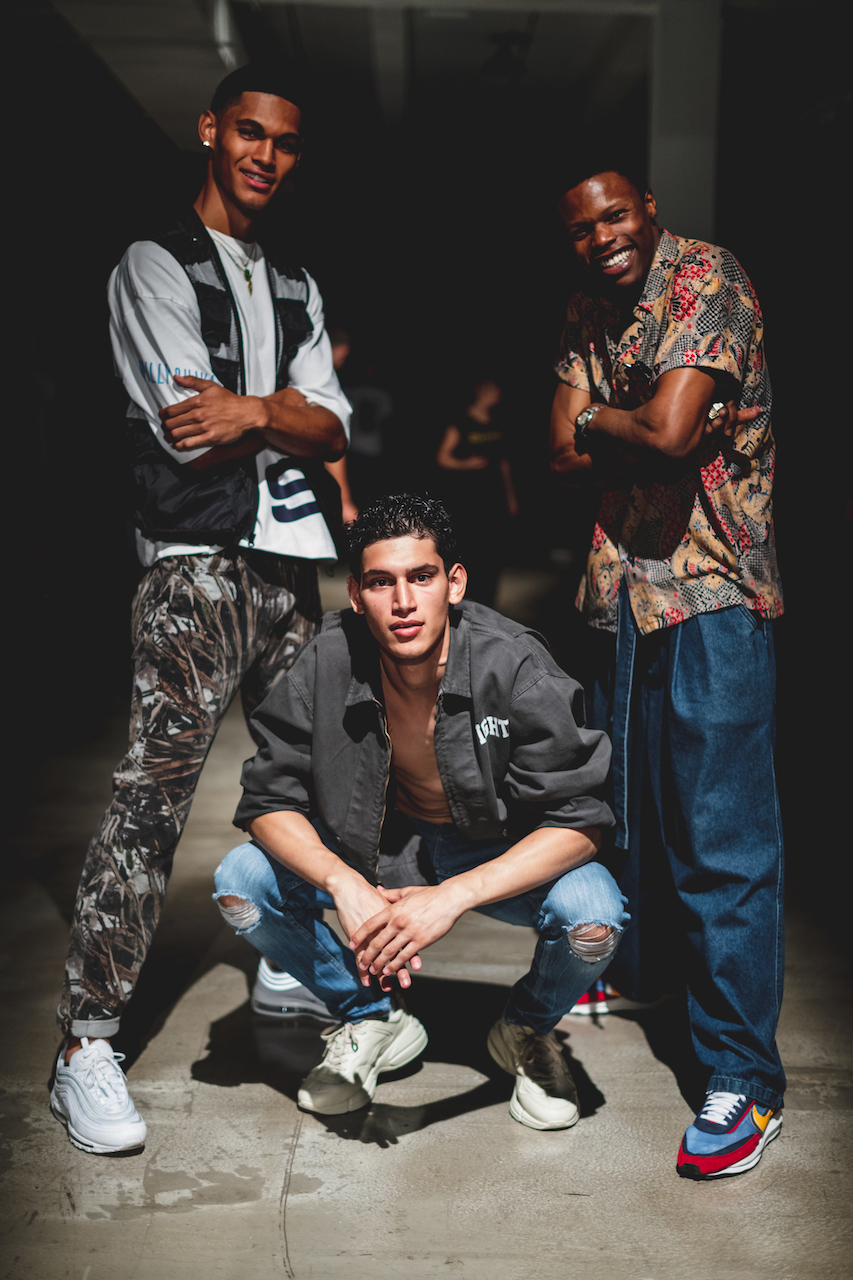

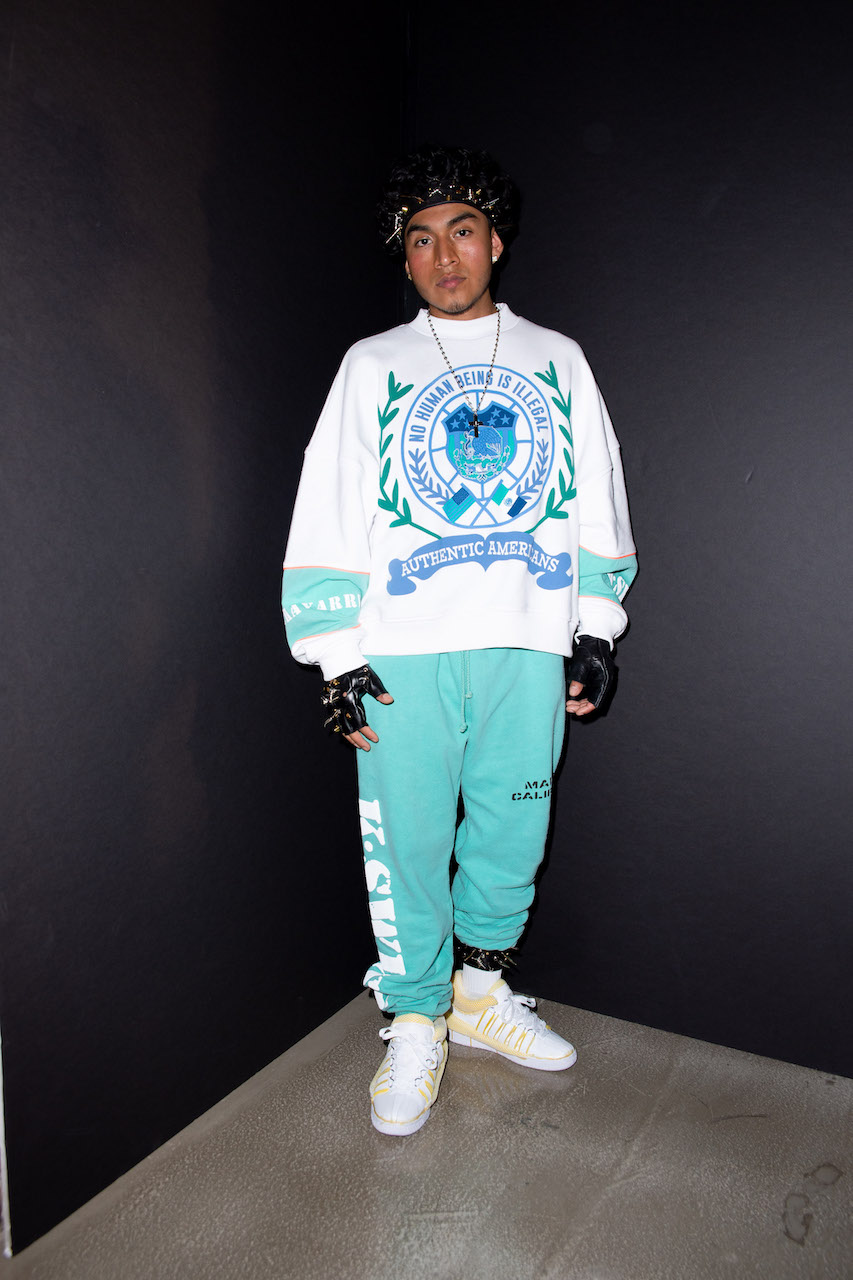

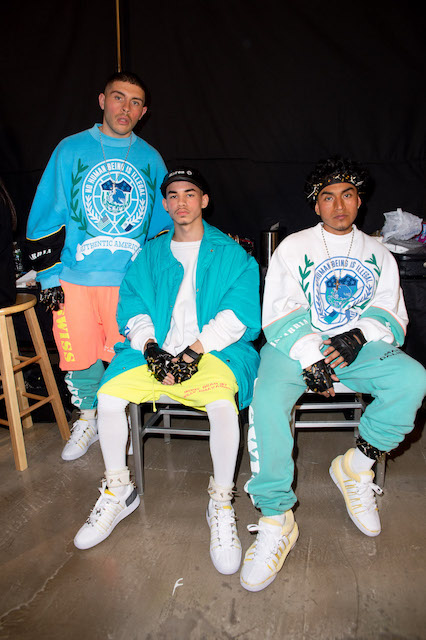

Willy Chavarria behind the scenes at one of his shows with model.

Chavarria recognizes he is far from the only designer who takes influence from cholo culture in designing. But, he is one of the few who realizes it and credits it.

However, what makes his designs even more special is that they facilitate social and political conversations. In Chavarria’s opinion, the world has been in need of a wake up call for a while.

“I often think of my collections as simply a reflection of the world,” says Chavarria. “I like to take what I see on the streets, re-work it, and then give it back to the world in a more beautiful light.”

Chavarria believes that good design comes from the heart, so he generally gravitates to things that are personal.

“Those things include the dignity of people of color and of LGBTQ+ people,” he says. “But there are so many issues in the world that could simply be solved with love and human compassion. So the underlying message in what I do is love.”

Chavarria believes fashion is truly reactive to the current state of the world. (Most notably documented by the supreme Robin Givhan).

In order to offer the world some sort of solace, Chavarria’s designs embody the cholo essence. He says his brand aesthetic is emotional elegance. His brand purpose is to make people feel as beautiful and powerful as they truly are.

“The fight that we have in us for creating change for the better is something I love to highlight,” says Chavarria.

Mainstream media seems to represent cholo and Chicano as one and the same, especially when it comes to the big screen, and Alaniz can attest to that. While they do fall into the same groups and conversations, they carry a significant difference in meaning.

Now is a good time to talk Mexican-American gang history. Sure, who doesn’t think about big, white tees, shaved heads, tattoos or getting jumped in by an old head? Many people don’t know that these street gangs, or cliques, go all the way back to the 1890s. However, the Zoot Suit Riots would be a major turning point in the evolution of gangs, especially when it comes to cholo culture.

The violence and protests were many times rooted in protection.

Chavarria says cholos emerged as the gang-related guardians of territories in cities and towns.

“My feeling has always been that Mexican generations feel robbed of their land from the Pilgrims and therefore have a need to claim land even if it is a city block,” he says.

With cholos, the pachuco style evolved into the modern outfit of self identification, he says.

“Oversized, clean, pressed, belted, sharp,” says Chavarria. “This strong style definition had huge influence on Chicano culture and the style was adopted by many brown people as a way to feel connected with our culture.”

For Alaniz, the distinction between cholos and Chicanos is clear. Cholo is a specific period where Mexican-American urban youth took to the streets to protect and fight against racial injustice. Meanwhile, the Chicano movement was based in the student movement, specifically youth in universities.

The thing about Yolanda Alaniz - she was there for the Chicano movement.

Raised by a single mother in the barrios, Alaniz was the oldest of seven children in a farmworker family. When thinking about her childhood, there is no pretty way of putting it - they grew up poor. However, when her mother wasn't working acres of farmland with sun blazing upon her back, she was an unstoppable force in the community advocating for Mexican-American workers.

Alaniz became the only one in her family to receive a college degree. At the University of Washington, she would be introduced to the Chicano movement as it was gaining momentum.

From that point on, politics and social activism flowed through her veins and she used her voice to speak against racial, gender and socio-economic inequality.

She says she felt the cholo movement didn’t feel like a political statement against all forms of oppression—by the government and other institutions—like the Chicano movement did. Instead it seemed like a violent revolt against law enforcement.

She advocated for Chicano studies on campus and hiring more Chicano professors. Later, she led the university’s first labor strike when she became an office assistant.

This, of course, did not come without scrutiny. As Alaniz continued to fight against inequality, she joined organizations that were not exclusively Chicano, such as Radical Women (RW) and Freedom Socialist Party (FSP). Her Chicana peers feared she was becoming white washed. In addition, at home things came to a boil as her husband exclaimed he wanted a full-time wife and not a part-time political wife.

Now in her 70s, she still actively fights for equality. Throughout the week you can find her using her voice to advocate for Black Lives Matter issues, LGBTQ+ movements, social feminist initiatives and much more.

Spoiler alert: Alaniz separated from her husband and is happily remarried.

“Never would I have imagined that I would be married to a white woman,” Alaniz says. However, the greatest lesson that Alaniz has learned from all of her life’s twists and turns is to embrace change.

“I came from barrio, became a writer and went to school,” said Alaniz. “It gives us hope anyone can change.”

Alaniz fully embraces resistance, believing that activism has to go beyond the individual. She strives to be a role model to her daughter, family and community.

“I want to leave the world better than I found it,” she says.

Although to Alaniz, “cholo” and “Chicano” will always be rooted in resistance and activism, she understands that the words have evolved.

Younger generations have used them as identifiers to express their Mexican-American pride.

Veronica Garza may not be from the same generation as Alaniz, but she can agree that she has seen the meanings of these words transform.

Garza agrees that “Chicano” initially was associated with political movement and identity. Now she believes the fight is different.

“Yes, we still are fighting, but it's a different process,” says Garza “We express these views online. We express our unhappiness via social media and discuss in different Facebook groups or with hashtags.”

In addition, she says that the word “cholo” still gets a bad rap.

“In my lifetime, I’ve seen an artistic movement into the mainstream--both good and bad,” she says. “English speakers embraced Selena. However, movies and TV continue to emphasize this one stereotypical aspect of the cholo identity.”

Veronica Garza performing her stand-up comedy.

Garza is a stand-up comedian, writer, host and actor—a true Jill of all trades. You may have seen her in the MTV’s Decoded series for Cholo 101. However, even she thinks the definitions are a little all over the place.

“From my observation, it seems as though we cannot come to agreement on the exact definition for either of the terms,” Garza says.

Even Willy Chavarria says the word “cholo” has different meanings all over the world.

“When I’m in Peru, ‘cholo’ is a word embraced by the forward thinking young people as a taking back of a derogatory term that meant being too ‘indio’ or too ‘culturally ethnic’,” he says. “Kind of like ‘country’ for white people.”

However, there is one thing everyone can agree on. Cholo means taking a stand.

Chavarria thinks back to his 2017 show, which took place right after the Trump election. At this time, the world felt a need to stand up for humanity, he says.

“My next show, CRUISING, took place in a raunchy gay bar and combined the cruising theme with the homophobic lowrider culture,” Chavrria says. “The crowd was full with straight people supporting queer identity.”

He continues, “As much as we see the bullshit in the world with blatant hate and oppression in our faces, it is empowering to know that we can be unified with others like us or who simply love us.”

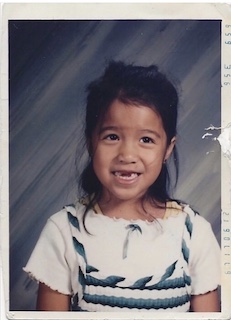

Mekita Rivas pictured in elementary school.

The Trump election not only sparked movements within the fashion world it also motivated others to use their voice and their platforms.

Mekita Rivas is an accomplished journalist and writer who has a deep passion concerning most issues going on in the world. Rivas has written for publications like Glamour Magazine, Refinery29 and the Washington Post. She is steadfast that the only issue that matters in 2020 is voting.

“These are unprecedented times,” she says “There’s a racist, misogynist, narcissistic sociopath in the White House who’s keeping brown kids in cages and destroying democracy in real-time. Nothing else matters if people don’t vote this monster out.”

She says the chola phase of her childhood is what helped get her to this point.

For Rivas, navigating her Chicana identity was a little tricky. Instead of rolling down the vibrant streets of East LA, Rivas came into her chola phase in the big Cornhusker State, also known as Nebraska. Born to a mother from the Philippines and a father from Mexico, Rivas was first-generation.

“It took me a long time to finally let go of this idea of being ‘half’ something — half Filipina or half Mexican — and instead embrace being the entirety of these identities,” she says “I am wholly Filipina, wholly Mexican, and wholly American because these are the cultures that shape who I am. As a Mexican-American woman, I also identify as Chicana.”

Mekita Rivas sporting her "chola bangs."

In high school, just as she was planning her quinceañera, she began to hang out with a few other Latinas. Trading in her puffy quince dress for all of the Hanes baggy sweatpants and oversized white T-shirts from the men’s section at Walmart, Rivas and her new friends’ chola phase began.

Tight bun secured with gobs of hair gel? Check. Big silver hoops? Check. Pencil-thin eyebrows? Check. Your best pharmacy lipstick? Check.

“I think I was yearning for a sense of belonging, and taking on this ‘chola’ persona was a way for me to do that,” she says.

Often not feeling “Chicana enough,” Rivas searched to find her own identity without having examples of what a strong Chicana looked like in real life.

Although she considers her chola phase to be over, it is something that will forever be a part of her. Even today, you can catch her rocking her long, dark hair effortlessly styled with gold hoops and a fierce red lip.

“That’s when I feel most powerful and unstoppable,” she says. “The quintessential chola ‘look’ embodies pure confidence and toughness. But that’s what the culture is all about: unapologetic ownership of your identity. That’s something I aspire to every single day.”

And, that’s exactly what Rivas is doing - owning it - whether it’s interviewing Maxine Waters on Capitol Hill or being secure in her Chicana identity, chola bangs included.

“Now I see that what made me ‘an outlier’ is really my super power. And there’s no such thing as ‘what a Chicana is supposed to be like.’ There are stereotypes and generalizations, but the culture is so much bigger than that. Have you ever met an Asian Chicana? If not, now you have.”

So let’s take a nice seventh-inning stretch to talk music.

If you haven’t put your elbows up side to side like a cholo on the dance floor, you really haven’t lived. Songs like “Lean Like a Cholo” have been on party playlists for what seems like forever.

Aside from its party starting capabilities, cholo music, especially cholo rap, has perpetuated hypermasculinity in its imagery and lyrics.

Obviously, we can’t talk about Chicano and cholo culture without talking about machismo. A skeleton in the closet, machismo is the core of Latinx masculinity and patriarchy. You know, it’s the attitude of “don’t cry,” “never show weakness” and “make sure you always get the girl.” In short, it’s the “be a man” of it all.

Remember Veronica Garza?

She says, “Toxic masculinity has been embedded into the culture for so long, it will take many generations to get rid of it.”

Now, a new era of cholo rappers are using cholo rap to fight against machismo, push boundaries and redefine what it means to be Chicano.

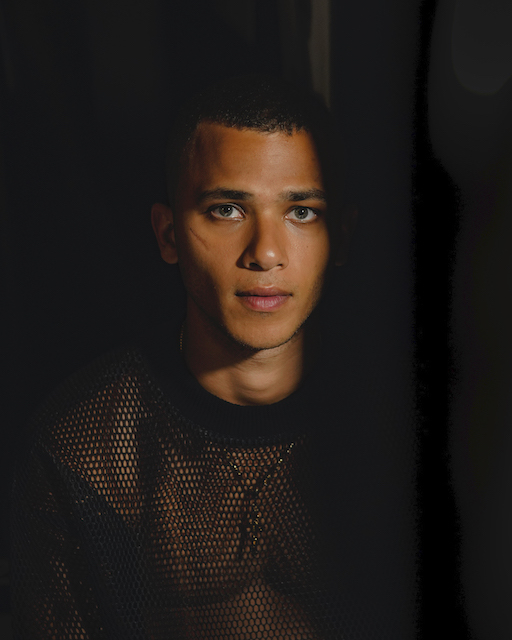

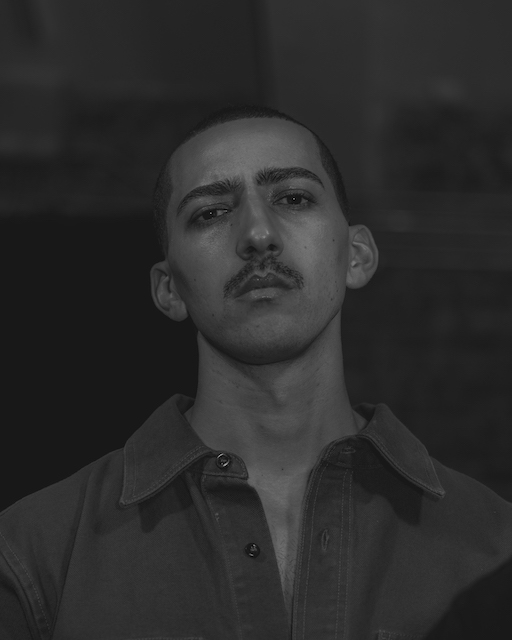

Baby Boi Slim posing in a photoshoot in his modern chola style.

Growing up in Boyle Heights in East LA, a rising rapper known as Baby Boi Slim was surrounded by Chicano culture all of his life.

“There's no escaping it,” Slim says “It's been here since the early 1900s but it really flourished in the 60s and 70s...It's evolved into what it is today.”

After spending countless hours writing lyrics to beats on Youtube, the rapper dived into the world of hip-hop five years ago thanks to a push from a fellow Chicana rapper and friend. He never had the desire to actually put anything out before then.

So how did Baby Boi Slim become a rising rap artist? It all started as an alter ego to talk about how he grew up.

“At first it was just self therapy,” he says “But after realizing how many like me grow up the same way, I decided to actually make it into something bigger.”

And that something bigger is being a voice for LGBTQ+ youth. Identifying as non-binary, the Chicano rapper is breaking down barriers.

“Being gay and Chicano is still a huge taboo today, even with the progress that has been made over the years,” he says “Our culture is still extremely toxic with masculinity. To me, showing that there is an LGBT presence in one of the most homophobic genres out there will hopefully open up discussions on how we can move forward as one.”

Baby Boi Slim recording in the studio.

According to Slim, rap has always been about channeling the anger and frustrations about growing up in a gritty environment. The OG roots of rap and hip-hop portrayed the struggle of survival.

“Now, you take that and add a Chicano and LGBTQ+, it just became three times as hard,” he says.

Reminiscing on his own personal journey of identity, Slim candidly shared that things certainly have not been easy. The rapper has had to take various measures to assure his safety, such as not revealing his real name or age due to receiving threats in the past.

“For years I was afraid to walk home from school,” says Slim “I've been robbed and threatened and seeing how scrawny I am, I was always the easy target. It wasn't until I went into high school and met my homeboys and homegirls that I picked up this ‘Trust No Man, Fear No Bitch’ mentality that helped me survive. Along with that, I owe part of it to the music I grew up on. I liked the stories of struggle as well as the stories of coming out on top, and this is where I am now.”

Follow step-by-step Baby Boi Slim's modern chola makeup routine for shows and photoshoots.

If video does not load, click here to download.

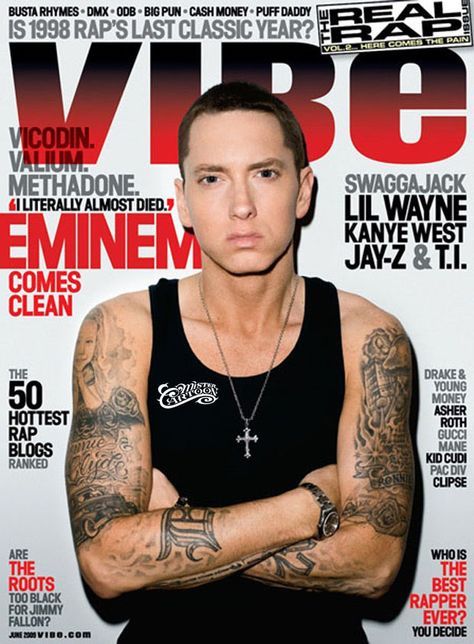

Eminem on the cover of VIBE magazine sporting his iconic tattoos done by Cartoon.

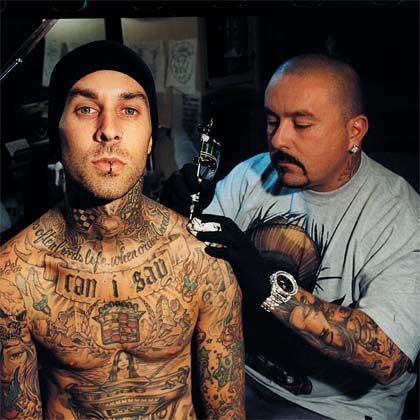

If you go south of Boyle Heights to San Pedro you’ll find the hometown of one of the most iconic tattoo and graffiti artists, Cartoon, who has put cholo culture on the international stage.

“Take the 110 to the end from USC and that was my stomping grounds,” Cartoon says.

Cartoon says he won the lottery when it came to parents. When they found out that he could draw, they were supportive of his artistry. His old man would often drop him off at the candy paint shop at the age of 12 where he was a fly on the wall as buckets were transformed into masterpieces.

He loved to draw and even airbrushed white tees. In school, he admitted he was a bit of a knucklehead as he wouldn’t complete assignments. However, he would use his artwork to help his teachers in the classroom, bartering for a passing “D”.

Things came to a halt when Cartoon caught a case for vandalism.

Fortunately, Cartoon knew that gangbanging and going to jail was not the path for him. However, he still loved the art, the music, the fashion, the women, and most of all the lowriders. So, he used his art to get them.

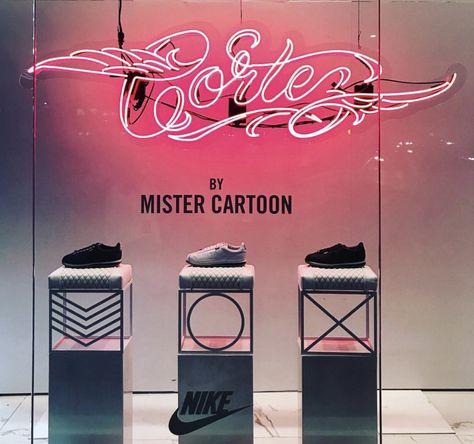

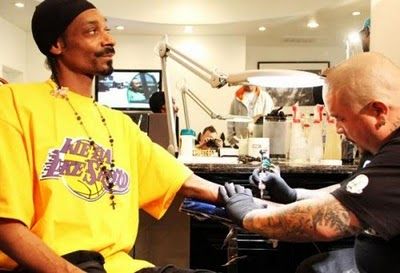

Now, if you don’t know who Mister Cartoon is, chances are that you’ve still seen his work. He’s collabed with pretty much every brand and entity that matters like Supreme, Nike, Vans, Grand Theft Auto and the Staples Center. He has tattooed Hollywood’s royalty such as Kobe Bryant, Snoop Dogg and even the Queen Bey herself.

Perhaps one of his most memorable clients is Eminem, who graced the cover of every major magazine standing with his arms folded showcasing Cartoon’s work. Who could forget the notorious portrait of Eminem’s daughter Hailie with a car and the script “Bonnie and Clyde”?

Cartoon in his Netflix documentary "LA Originals."

Although there’s no doubt that Cartoon loves what he does and is “the end all be all” of the tattoo, graffiti and art world, he makes one thing very clear.

“I’m not trying to sell my culture,” Cartoon says. “I’m not trying to sell my shit to these people. It’s just the way I draw. It’s just my style.”

He does appreciate the love and reception he’s gotten for his work and in some way believes that outsiders are saving the artform.

Take 50 Cent, for example. Cartoon says many people love the tattoo on the rapper’s back. However, they don’t realize they’re approving Chicano art. It just happens to be on a New York rapper, he says.

Behind the canvas of tattoos snaking up his neck and arms, Cartoon is an unexpected yet delightful self-help guru. If one thing ever remains true, Cartoon will always shoot straight and, unlike others, he doesn’t mind giving his secrets away.

“It was so hard to get this information coming up about Chicano art, how to paint candy about pin-stripping and gold leaves,” he says. “A lot of these old guys didn’t want to give me the information.”

The only way to keep it alive is to give it away, he says.

For over 20 years, Cartoon has spoken at schools to inspire and ensure the success of those coming after him.

“I give them internships,” he says “I take them under my belt and teach them.”

Cartoon also feels a need to help change the narrative around cholo and Chicano culture.

“The way they put us out there a lot of times we look crazy,” he says. “We have a machine gun and we got an uzi. We’re killing somebody or selling dope.”

This April, Cartoon put out his own film on Netflix, “LA Originals,” that documents his own personal story, dives into hip-hop and street culture and features Kobe Bryant and Snoop Dogg.

At 50 years old, Cartoon believes there's still more to accomplish. There’s just no telling what else he has up his (tattoo) sleeve.

There’s no doubt that individuals like Baby Boi Slim, Mekita Rivas, Willy Chavarria and even Cartoon are taking their Mexican-American identity into their own hands.

Some say you can’t know where you’re going without acknowledging where you’ve been. But where does this leave this next generation of Mexicans when it comes to their Chicanx identity and any future cholo phases?

Conversations regarding the intersection of race, sexual identity and politics seemed even more heightened in this new decade.

Listen to a Q+A with Xorje Olivares of Sirius XM as he discusses the present state of Chicanidad.

It’s safe to say that cholo culture is more than riding down Sunset in a candy-coated Impala or going to Sephora in order to draw on the most perfect eyeliner wing. It’s more than negative stereotypes of gangbanging on the blocks of East LA. It is history. It is a culture. It is resistance and activism.

The word “cholo” is ever changing but also powerful.

Mekita Rivas says it best:

“It’s a reclaiming of a once derogatory term. It’s openly embracing and being proud of mixed Latino heritage. Of course there are visual cues like how someone dresses or what kind of car they drive that could be representative of chola/o culture, but I think at its essence, the culture is about taking power back from oppressors.”

© Ari Taylor 2020 | Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism