Whenever a rigid system, like our current healthcare, insurance, and social services organizations, is put in place, usually by old white men, communities form to fill in the cracks in this system. The tradition of women being doulas and midwives is as old as birth itself. So is the tradition of quiet revolutions full of fire and healing. Doulas aren't afraid to speak their mind to the medical establishment, and one of their most important goals is to empower their clients to do the same.

Los Angeles is a place where motherhood is packaged and commodified for the average American viewer and consumer. This is the land of tabloid pregnancy rumors, reality-television births, and mommy blogs, often filtered through a male perspective. While Gwyneth Paltrow and her public relations team set her up as the second coming of the Madonna, women like Brown and Michelle Sanders are proving that the strength of motherhood is something quite different. Sanders is a doula too - and the way her experiences parallel Brown's show that everyone is just one bad day away from being out on the streets too.

As the work of doulas like Sanders help mothers like Brown prepare for the birthing process, maternity homes can give her a stable place to live and offer parenting, health, and personal finance classes to help her prepare for the arrival of her son. These programs, which offer four to 10 beds, are a blessing for a very small percentage of pregnant women, but strict admission policies and house rules keep them inaccessible to many. They also can't fully provide emotional support. "These shelters, they will drive them to the hospital while in labor, but they are supposed to be outside the room," says doula Giuditta Tornetta.

To Tornetta and many others, this isn't enough support for traumatized, homeless women. Dealing with the emotions of pregnancy and postpartum while homeless is like, "putting alcohol on fire," Tornetta says.

Brown is no exception.

The doulas who gather at St. John's Hospital in Santa Monica are very familiar with this phenomenon.

Clinical therapist and doula April Fissell's office is dark, quiet, and cozy. It's also crowded. Nearly a dozen women have met to discuss their work. Fissell leads the group with ease. She applies the same observational skills she uses in her practice to teach the class. She immediately recognizes that one woman has had a very bad day by body language alone. Fissell refuses to continue the class until she's talked her student through her experiences and made her feel comfortable. Now, they get down to the doula talk.

The use of doulas grew in the 1960s, and the concept is now ubiquitous with a certain type of expectant mother. The work of modern doulas turns that concept on its head. Gone is the idea of a New Age caregiver, who comes bearing whale sound CDs and sage to smudge. Fissell's group watches lectures on evolutionary biology. They use the examples of Ron and Hermione to talk about the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. They trade tips on how to stand up to pushy doctors, how to make friends with nurses, and how to transform the harsh lights and sharp sounds of a hospital room into a space of peace for their clients. Their mission: to make sure their clients understand and consent to every step of their medical treatment.

The doulas also talk about the concept of the "ancient pathway." It's the most basic instinct all humans possess, deep in the foundations of our DNA. It isn't fight or flight. It's freeze. You don't just believe you're in danger. You believe you're going to die.

The doulas speak of women who, when faced with the birth of their child, go into a fetal position. The baby doesn't come. It isn't safe. Doula Emma Bird recalls one expecting client. The 18-year-old was in the middle of labor when she began flashing back to her childhood being smuggled from Honduras to the United States. As she relived her trauma, her body refused to push.

Tornetta is the head of the Joy in Birthing Foundation, a non-profit doula outreach center. She believes that this work is essential because "childbirth is a very emotional, very spiritual, very intimate moment. And for a woman to be alone is horrible." She acknowledges that trauma, depression, instability, and fear combine to create a torrent of anxiety and pain. Fissell calls it an "aching, gaping need" for support, help, and acknowledgement.

Pregnancy can and does retraumatize homeless women, many of whom have experienced domestic violence, food instability, and more. Once that initial event has stripped away their defenses, their bodies will remember the trauma. It finds its way back in.

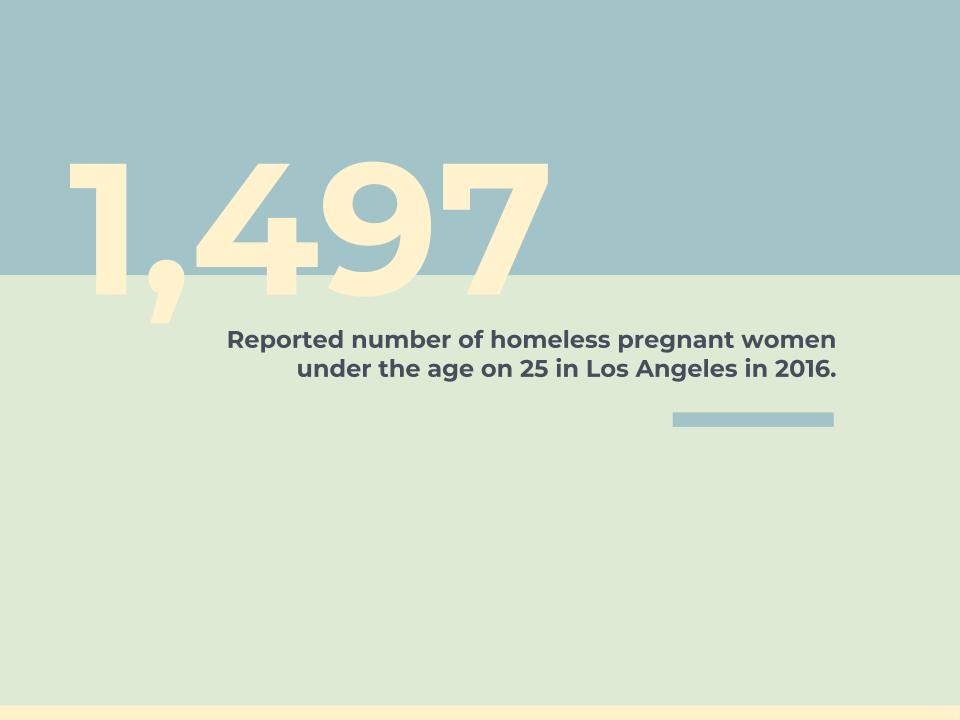

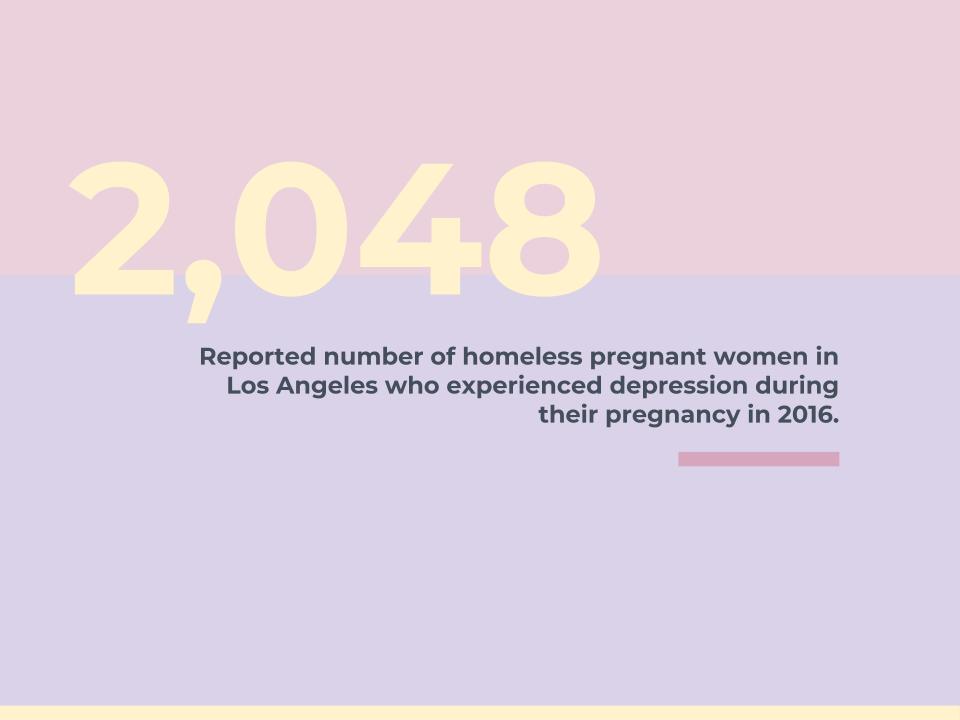

Every two years, the Los Angeles County DPH commissions a study by the Los Angeles Mommy and Baby Project (LAMB) to address fetal mortality rates in Los Angeles County. The researchers at LAMB named four factors leading to poor birth outcomes: preconception health, perinatal mental health, racial discrimination, and body weight. The first three of these disproportionately affect homeless women.

Homeless women must play "catch-up" during their pregnancy. Many start off malnourished, uninsured, and depressed. Now, they need doctor's appointments and prenatal vitamins. A woman with no possessions of her own is given a list of strollers, car seats, baby clothes, diapers, changing stations and more. It would overwhelm anyone in a stable situation, and most of these women are not in stable situations. While they are carrying their child, homeless women are twice as likely to suffer from depression and more than three times as likely to suffer from domestic violence, according to the 2016 LAMB study.

Brown faces many of these issues. She suffers from depression. She has been a victim of domestic violence. She has lost her job and has lived in an unsafe neighborhood. She has been around people who use hard drugs. She is black.

So is Sanders. Sanders "caught her first baby," as they say in the doula industry, 20 years earlier in her cousin's car. Her cousin couldn't get to the hospital in time, and Sanders knew she had to step in. Little did she know that this would lead to a new vocation that gives her satisfaction and emotional fulfillment. "I was like her doula," Sanders explains, "Didn't even know what a doula was at that time."

The journey has been a long one. Like Brown, Sanders has experienced homelessness in her life. She also suffers from depression. She also has been a victim of domestic violence. She also lost her job and lived in an unsafe neighborhood.

She also doesn't fit the stereotype of a homeless woman.

MEET MICHELLE

Sanders started at Cedars Sinai in housekeeping and worked her way up to training as a surgical technician. She can still remember the day her promising career disappeared in an instant. Right before she was about to move into a nice townhouse, she slipped on a pool of blood and damaged her knees and back. Even after several surgeries, she never recovered her full range of motion.

Her injury cost her her job, and the disability payments weren't enough to move into the townhouse. She and her family were out on the streets. Her children went to stay with relatives while Sanders slept in her car. If they asked, she told them she was staying with a friend.

Finally, Sanders found housing through a good friend and sympathetic landlord. She and her children have now been living in a neat, little house in South LA for 14 months.

Sanders told herself that she could view her accident as a tragedy or an opportunity. She chose to see it as an opportunity and began charging for doula services she had been providing to friends and family for free. Now, she describes herself as "peaceful." "I had to kind of realize that everything I had lost or even the things I had thought I lost...everything has come back to me, but greater," she explains. She takes the lessons she learned and applies them to her work: "There's a lot of stuff that I went through that I feel like this is actually why."

Sanders sees her work as dismantling the birth system set up by white, male medical providers. In her previous medical career, she had seen women triggered by oblivious doctors, unable to dilate, and rushed into C-sections they might not have needed. "If it's a healthy pregnancy," she warns, "Stay away from the hospital."

Sanders has also seen hospital discrimination at every level. Race is one of the most important indicators for adverse birth outcomes and maternity mortality. "Black women, women of color, we die four times more than white women in the hospital," Sanders says. "You know maternal death across the board in the United States is ridiculous. It's crazy. It's scary. People don't talk about it, but it's a real issue. But for black women in particular, it's a lot worse. It's a lot more dangerous for us."

Black, pregnant women are 13 times more likely to be homeless than white, pregnant women, according to the LAMB study. One of every 100 pregnant white women is homeless. One of every seven pregnant black women is homeless.

Brown talks about her discomfort with a healthcare system dominated by white men, at least on the surface: "A lot of times when people are getting help at these different places, they might see a lot of one color and they don't think that these other races are helping. They might be more behind the scenes." She has asked for a black doula in her birthing plan.

Brown is very vocal about wanting a doula. Harvest Home is happy to help. Brown's new residence is a quiet, older house in Santa Monica filled with parenting books and chore charts. It's also one of the few organizations that focuses on the health of the mother instead of merely the health of the baby.

INSIDE HARVEST HOME: A 360 EXPERIENCE

Director Sarah Wilson rejects the idea of Harvest Home as a shelter. We are a program, not just a shelter,

she says. We provide women with housing. We also provide them with everything else.

At Harvest Home, this means cooking, nutrition, health, financial, and parenting classes. Wilson believes that, It is really important for women to not just have a safe place when they're pregnant, but also for them to be equipped with the tools they need to be able to parent their children.

One of the most important facets of their program is emotional well-being. Wilson says the program is designed to help, that person look inside to be able to see what trauma they've experienced in the past; what barriers are there that are keeping them from being able to move forward or what healing they need in that area.

Another challenge, Wilson says, is just helping women to be OK with seeking support and receiving support in that area of their lives as well. And so that's a huge part of knowing what their signs are, when they need to ask for help, and not being afraid to invite others into that.

One of the first things Wilson does when one of her clients goes into labor: call the doula. Some of our moms have family members in the picture or dads that are there; some don't really have any other support,

Wilson says. Having those doulas there is really a tremendous support to the moms.

Wilson believes that it is this aspect of emotional support through fellow moms, program employees, and doulas that accounts for Harvest Home's surprisingly low postpartum rates: Postpartum depression is actually one of the key reasons that we brought our therapy services in house a few years ago. And interestingly you would think that our postpartum depression rates would be really high. We've actually found that they're really low. And the only thing we can attribute that to is the amount of support that women are receiving - so one being in a supportive environment and supportive community with postpartum doulas that come here afterwards.

Women are allowed to stay with their infants in Harvest Home for up to six months after birth.

Tornetta, who has worked extensively with Harvest Home, says their system only works for certain personality types. Sometimes when you are faced with so many difficulties in your life, rules can be a shelter and can feel good,

she says. Sometimes they can feel like 'here is somebody else trying to tell you what to do and making you feel like you are nothing.'

Unfortunately, competition for the spaces is fierce. This is because, like Harvest Home, most homes don't consider themselves shelters but programs. They sacrifice quantity for quality when it comes to classes, services, and support. Programs like Angels Way Maternity Home in Woodland Hills turn their small size into a feature. Betty Breneman, executive director of the home, says of their four-bed program: A wonderful thing about having a small maternity home, which is what we are, is that the women who come to us get to experience living in a family environment.

However, these programs also acknowledge the need for their services. Kali Ratzlaff, program assistant at the six-bed Elizabeth House in Pasadena says, As soon as we have one leave, we have a whole list of people waiting in the wings.

As one of 10 women in a pool of 500, Brown had a one-in-50 chance of getting into Harvest Home.

She's lucky to be at the top of the list.

This isn't the first time Brown has welcomed a baby. DeShaun was her firstborn. He looked like my little twin. He was super cute,

Brown remembers. He had really fat chubby cheeks.

DeShaun was born in 2008. Brown recalls the trauma of his birth: Right after he was born I had to stay in the hospital for three days. So then I wasn't with him that time.

When she finally got to see him, he was in the little bed and I didn't get to hold him until he was two months old, and it was just really heartbreaking.

Brown received a crash course in nursing and technology. She was shown how to maintain the machines that helped DeShaun breathe and sleep and live. Although she used to worry that her new child would have the same genetic disorder as DeShaun, she's come to peace with it: "If my baby comes out with Down's syndrome, I'm still going to love my child, and I'm going to want to take care of my child."

That's exactly what Brown did with DeShaun. Every day she showed him how happy she was to be his mother. For two years, Brown watched as her son smiled, laughed, and played. When he died in 2010, Brown knows that he knew how much he was loved.

SHAINA'S TATTOOS

Brown tried to piece her life back together after the devastating loss. She encountered setback after setback. After her hours were cut back at Staples Center, Brown hit her limit. She couldn't keep her mental anguish hidden any longer: "There's certain events that you go through that other people don't experience so they don't understand it." Her mother was so worried about her, she had Brown institutionalized.

"I just remember one day the cops coming in and then the ambulance taking me to a hospital," Brown recalls. "When I got out I went back to my mom's house and all my stuff was outside in the backyard." Her mother was on Section 8 housing, and Brown was not legally allowed to live in the house. Brown tried to regroup, but there were no job opportunities available. She looked for work but started, "crying in interviews as soon as they asked me about my time history, like 'why haven't you been working for this amount of time' and having to explain that over and over again in each interview."

Brown's mother soon left the state entirely. With no support system, Brown was homeless, jobless, depressed, and alone.

Brown tried her best to adjust to life on the streets. She picked up things quickly. A gym membership could get her a hot shower before an important interview. Certain Starbucks would give out free water. The heating grate in front of El Camino College was a warm place at night. One of the challenges Brown never would have expected was the sheer boredom. "When you're homeless, you're trying to keep yourself stimulated," Brown explains. "I found myself going to places where there is just a lot of people where I could just sit and look and think, you know what I mean, and just wonder." Brown never gave up on her art or her curiosity.

It was on the streets that she met the father of her child. The two entered a relationship full of angry outbursts that Brown calls her lover's immaturity: "He's young and he hasn't had any type of experience or years behind his thought pattern yet." After one final confrontation, Brown called the police. "So I decided that I was not going to be in a relationship with him anymore. And then like two weeks later I found out I was pregnant," she remembers.

Brown handled her pregnancy in stride. "I feel blessed to be able to be a single parent where I don't have to deal with the craziness of another family or another person wanting to be the boss of my kid," she explains. "I get to make all the decisions."

The first decision she made was to call 211, the Los Angeles call line that provides referrals for several social services organizations. The service connected her to Harvest Home.

Brown is also a legacy. Her mother told her that she had also stayed in Harvest Home when she was pregnant with Brown's brother. She spoke about it with fond memories. Brown now spends her days filling out parenting workbooks and preparing for the arrival of her son, Monsieur. She picked the name because she wants him to be able to close his eyes and imagine he is in France whenever anyone calls for him.

Now, all she needs is a doula...