On the other side of the world from Thian Fah, in the heart of Santa Monica, California, sits the Emperor's College of Traditional Oriental Medicine. The school and clinic occupy most of a two-story office complex just a few blocks from the city's famous pier. Some 200 students are enrolled in the school's Master of Traditional Oriental Medicine program, with an additional 50 in the Doctor of Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine program.

"One of the common threads that bridge their [our students'] stories are personal testimonies of their healing experience," says Amber Johnson, director of admissions for Emperor's College. "Unfortunately, our healthcare system in the United States is really challenged in a lot of aspects and people don't feel like they are getting the care that is needed."

Johnson says that many students gain an interest in TCM after unsuccessful treatments in the mainstream medical system leave them disillusioned and open to alternatives. When acupuncture succeeds where prescription drugs have failed, they become advocates of TCM and want to pursue a career in the field.

"I would say most of them have had some sort of profound experience with acupuncture," says Yun Kim, president of the Emperor's College. According to Kim, Western medicine's proclivity for steroids and painkillers leads to treatments that mask symptoms rather than dealing with the underlying issues. "It's not really getting to the root of the problem," says Kim.

Click above to take a tour of the Emperor's College of Traditional Oriential Medicine.

Click above to take a tour of the Emperor's College of Traditional Oriential Medicine.

The Emperor's College classrooms, offices and other facilities are spread throughout this medical plaza in Santa Monica. (Photo by James B. Cutchin)

X

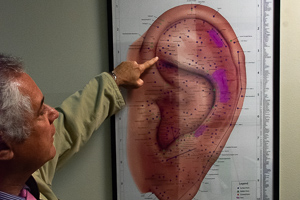

Acupuncture is the main way most Americans will encounter TCM. Forty-seven states have laws regulating the practice of acupuncture, with an estimated 35,000 state-licensed practitioners nationwide. Acupuncturists are now a common feature in many U.S. cancer treatment facilities, presented as an option to patients for managing nausea and vomiting caused by chemotherapy. Most herbal mixtures, on the other hand, are considered supplements under federal law and are regulated only by the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994. The act defines such supplements as a food product, limiting their ability to be used in a mainstream clinical setting. In 2012, the National Institutes of Health reported that a quarter of Americans using acupuncture had it covered by their insurance. To date, no major insurers cover herbal medications.

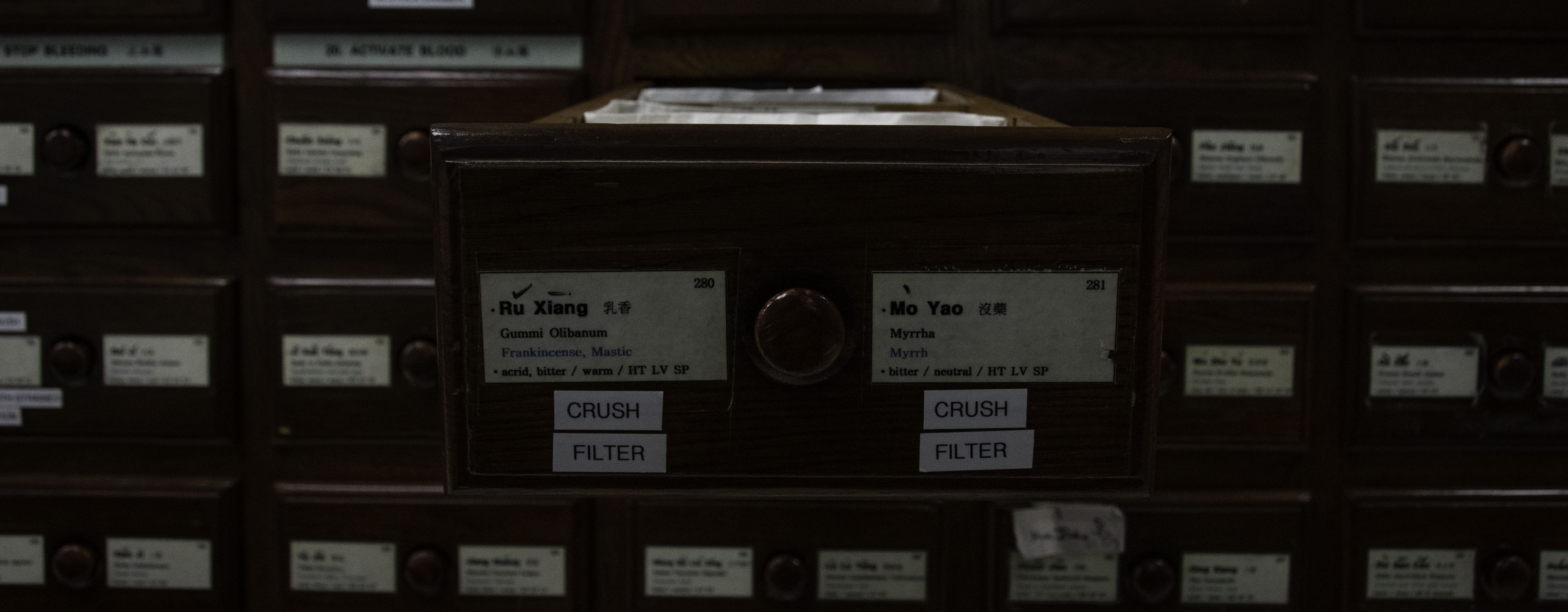

Ji Zhang, one of Los Angeles' most established Chinese herbalists, is an instructor at the Emperor's College. Zhang sees patients at his private clinic, Ji Acupuncture and Herbs, which he opened in 1994.

"Acupuncture is like surgery, herbs are like drugs," says Zhang. "Many people in the U.S. know [about] acupuncture for pain management, but not many people know herbs are good for a much wider variety of things. Gynecology, dermatology, many things can be worked out through herbs."

Zhang describes acupuncture as a small, niche area of TCM, which overshadows the bulk of the field's scope in the United States. "In Chinese hospitals you will have over 10 different [TCM] departments. Only one is acupuncture, all of the rest are herbs. The treatment range is much greater." Zhang says he successfully treats everything from infertility to asthma using herbal remedies.

Despite his conviction of their efficacy, however, Zhang is not optimistic about the future of TCM herbal medicines in the U.S. healthcare system. He says the main sticking point is how drugs are tested and approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

"They require a single chemical. One herb includes so many different components," explains Zhang. "We don't use a single herb, we use a formula that can include over 10 different herbs that work together. During the boiling, some chemical reaction also occurs. Every week we might use a different formula. How can you do a clinical trial on that?"

This sort of variation, inherent in the traditional administration of TCM, creates quality-control issues unacceptable to many Western regulators. It is also why some practitioners would prefer a move away from clinics based around one-off personalized decoctions (boiled herbal mixtures). Instead, they favor a more systematized application based around so-called patent medicines — standardized, prepackaged herbal treatments, often in tablet or pill form.

Weijun Zhang (no relation) of the University of California, Los Angles Center for East-West Medicine, works at the boundary between TCM and the mainstream U.S. healthcare system. His organization operates several Los Angeles-area clinics which treat patients through a mixture of TCM and mainstream medical procedures. The center also leads a range of research and educational programs to promote the integration of the two fields.

"Herbs come in three different types," says Zhang. "One is raw, one is patent herbal medicine and then there is single-ingredient. The final one is basically a Western drug."

Three types of herbs (from left): a raw herbal perscription, a box of Po Chai Pills patent medicine and a bottle of bai shao (white peony root) extract. (Photos by James B. Cutchin)

Three types of herbs (from left): a raw herbal perscription, a box of Po Chai Pills patent medicine and a bottle of bai shao (white peony root) extract. (Photos by James B. Cutchin)

Zhang gestures at an illustration of the three types of herbal application methods as he continues. "These two, no problem," he says of patent herbs and single-ingredient medicines. "This one, is questionable," he says pointing at the raw herbal treatment. He goes on to explain that variability and lack of standardization are the key flaws in the traditional clinical model.

"The issue is this — for this week I see you, and you are this pattern," Zhang says, referring to the patterns of symptoms used to diagnose patients in TCM. "I prescribe some herbs, I combine them, I use them in some formula. This isn't so fixed, so this part is questionable in terms of evidence [of effectiveness]."

Zhang says that the chemical variability of raw herbs themselves are also an issue with standardizing performance in the classical TCM setting. "If you harvest the same herbs today and then harvest them in the summertime, they're different even though they have the same name. But you [the doctor] still prescribe the same thing because you believe your diagnostic system is correct. But actually, the stuff is different. So how do you prove this with evidence? You cannot."

Zhang contends that patent medicines address this issue by offering standardized doses of TCM herbs. He divides these products into three main types: new formulas identified through private-sector or academic research, family recipes passed down through generations at private clinics and well-documented classical formulas.

"These," Zhang says of the first type, "are produced under industrial standards. They've undergone rigorous research." He holds that the second type end up undergoing similar procedures before reaching store shelves. "Before a company produces it, they will want to see evidence that it works and that it's safe," says Zhang.

Zhang says the final type, classical formulas, have had their effectiveness time-tested. "They've been used for 2,000 years; they've already proved it's useful. There's no issue of evidence with these."