FEELING "OTHER"

For Quitzon, the internal battle between her two cultures often presents itself during the holidays when she celebrates with both parts of her family.

Her father's side, which she mainly grew up with, usually lines up a parade of Filipino food for Christmas, like chicken adobo, pancit noodles, lumpia spring rolls and a roasted pig. But being the only one there with part-Salvadoran blood, Quitzon said she couldn't help but not feel "Filipino enough."

But for her mother's side, Quitzon said she braces herself to be the only one there who family members call "La Chinita," a word for "little Asian girl."

Quitzon shared how the clash between her two bloodlines even went skin deep as she grew up with conflicting beauty standards from both sides. By Filipino standards, lighter skin is typically preferred, which contested with her darker skin tone, she said. Quitzon remembers when a family member called her "dark" and "dirty" after she spent the afternoon playing in the sun. It was a seemingly harmless but stinging joke that stuck with her until adulthood.

"For a while I really believed if I was lighter I'd be prettier," Quitzon said. "But when I got older I started to understand whatever we have to work with is beautiful and it's better to accept yourself than to be something you're not."

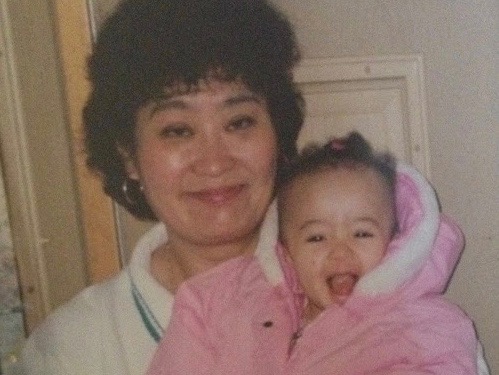

Effie Makrygiannis, 24, describes herself as "Japanese and Greek with a sprinkle of Hawaiian."

"If I'm in my group of friends on the east coast who are white, I know I look distinctly Asian," Makrygiannis said. "However, when I was in fifth and sixth grade hanging out with my friends who are Asian, I look distinctly white. If you put me in either one of the homogenous populations, I stand out."

"If you put me in either one of the homogenous populations, I stand out."

In Greece, where she has visited for every summer of her life, she said people automatically assume she is a tourist.

"Every single year, without fail, I'll be walking down the street and hear men or women say 'Look at that Chinese girl here for vacation' or make a comment about my outfit," Makrygiannis said. "Then I look at them and say [in Greek] 'I didn't hear you could you say that last part again?'"

But not being solely Greek did not inhibit her ability to speak the language with proper grammar, cook traditional dishes and know the different islands that comprise part of the nation.

"I do feel like I have to prove myself because I want so badly to be accepted on both ends," Makrygiannis said.

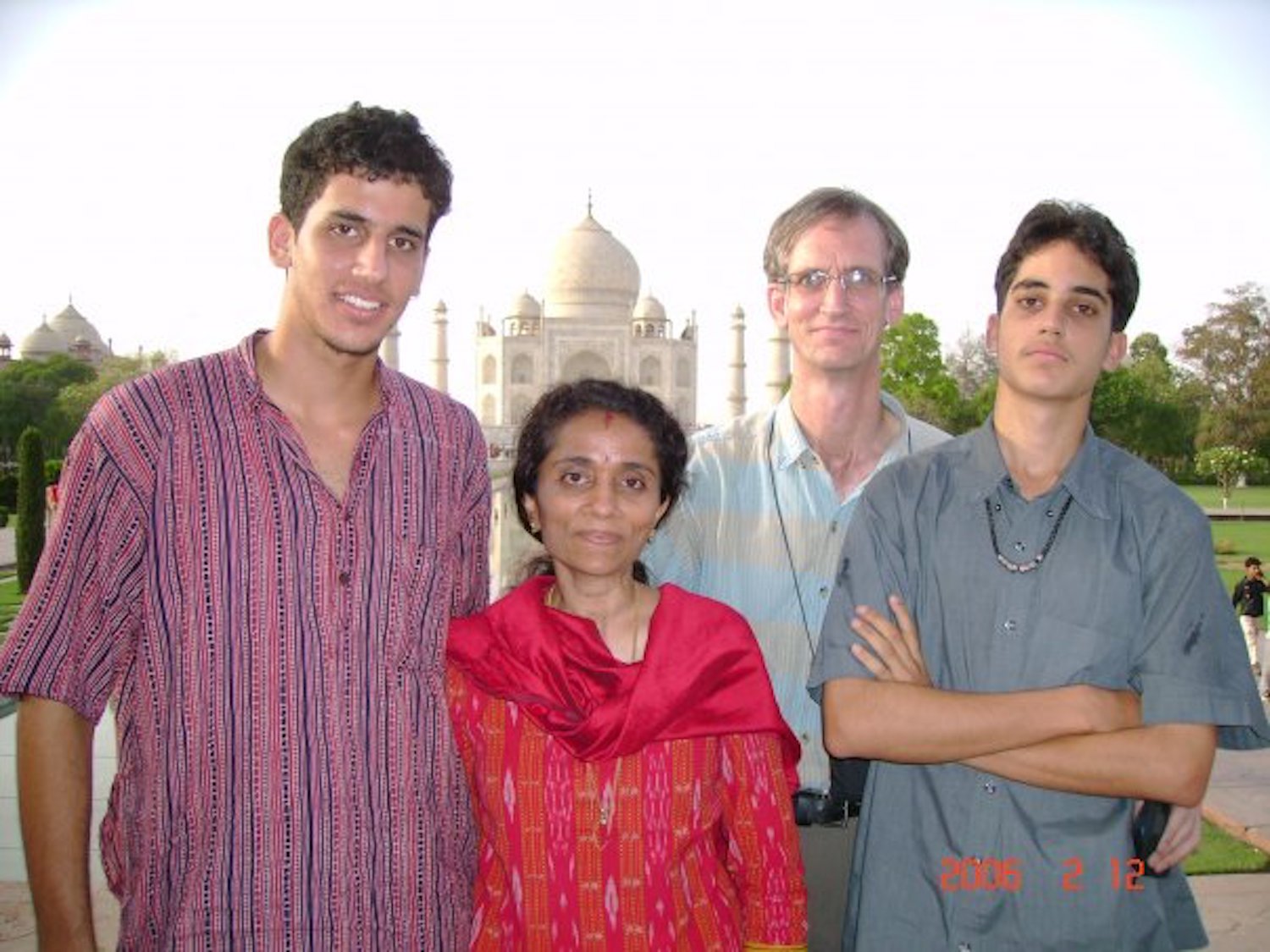

Actor Naren Weiss, the son of an American father and Indian mother, said he makes efforts to avoid being typecast as the terrorist or the "tech guy" in television. But casting directors for other roles sometimes deemed him as not being "Indian enough" just by the sight of his last name.

It's a tightrope Weiss said he has tried to balance on for nearly his whole life living in America then India.

"When I was in the U.S. I was only considered Indian," Weiss, 27, said. "But then I had to go to India only to be treated as American. You are always the other, which is fine because when you get older you find out that it's so much more fun not to conform."

"When you get older you find out that it's so much more fun not to conform."

Now living in New York City, Weiss was cast in Andi's play that ran this summer about a three generational Indian family where the youngest children are biracial.

For Andi, mixed representation in media is lacking, which is something she works through in her writing.

Another instance of feeling "other" that reoccurs for people of mixed race is when forms attached to college applications and standardized tests ask individuals to choose a box in the ethnicity category.

"I have to sit there and think which one am I today?" Makrygiannis said. "That's really when being hapa gets a little hard because I don't feel like I should have to choose. When I choose one, I feel like I'm letting down the other."

The Census Bureau only began allowing people to select more than one racial category in 2000, according to the Pew Research Center.

Student Mariko Daisey, 22, said filling her college applications in 2014 was the first time she could finally check all that applied to her.

"For a while, I didn't want to check one box, so I checked 'Other,'" Daisey, who is Black, Japanese and Nanticoke Indian, said. "Then I thought 'No, I want people to know who I am' and having that option helps me reaffirm my identity."