Overeducated and Underemployed

Filipino Migrants Armed with Degrees

Only Find Work as Caregivers

Dec 6, 2017

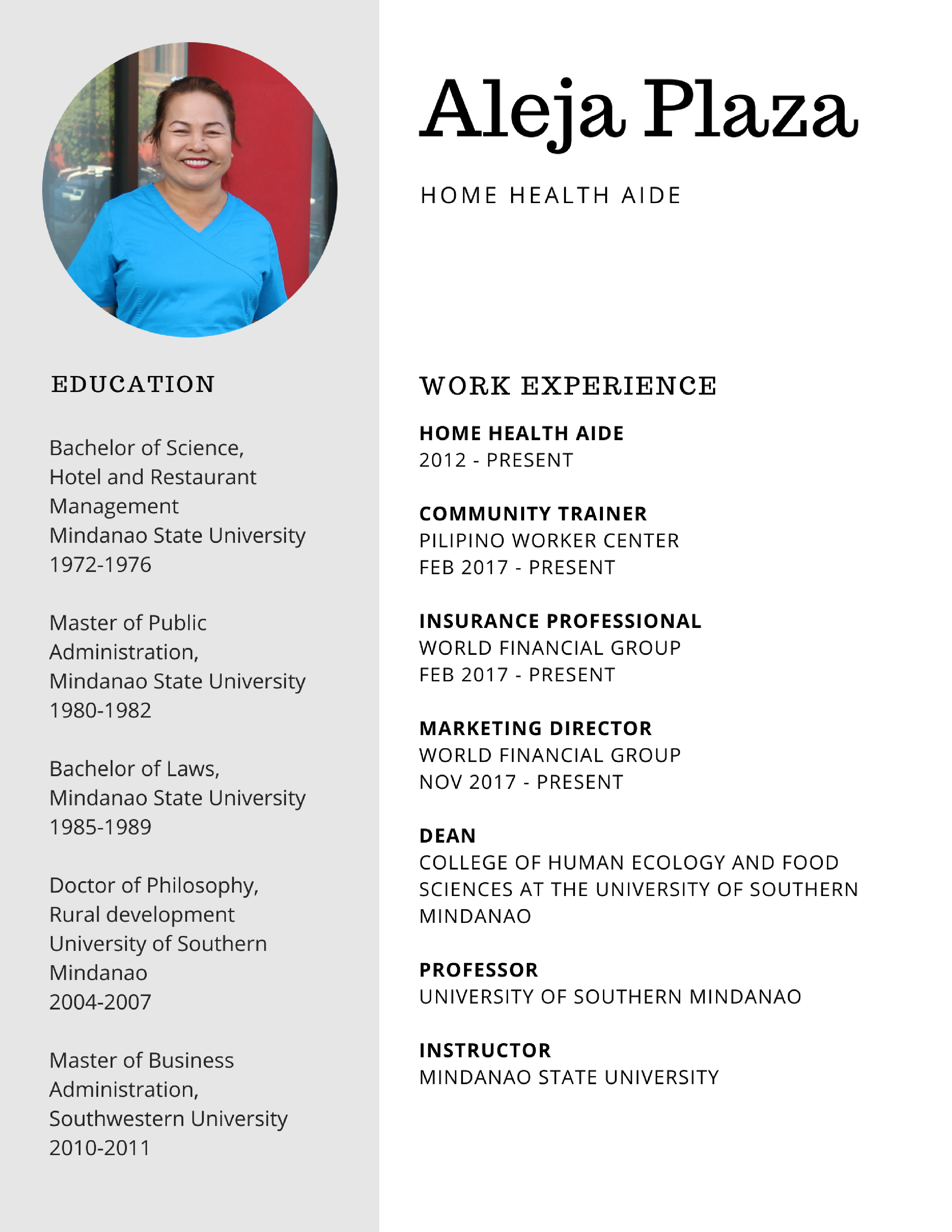

Once a university dean in the Philippines, Aleja Plaza never thought she would become a caregiver for the elderly. Since she came to Los Angeles from Mindanao in 2012, her daily routine has switched from approving courses and conducting research to changing diapers and spoon feeding senior citizens.

“I’d better burn all my diplomas because they are useless,” said Plaza, the 57-year-old caregiver who holds five college degrees. “Sometimes I feel that it’s a waste of time getting all these diplomas and then I’m working this kind of job. And then I got all these humiliations,” she said, recalling that one of her elderly patients even called her “smart bitch” and told her to get out.

Like Plaza, many highly educated Filipinos with a high-status identity suddenly have found themselves doing what many see as low-status work when they left home for better opportunities in a foreign country.

The Philippine Statistics Authority reports that among the 2.2 million overseas Filipino workers around the world in 2016, 1 in 3 is employed in an “elementary occupation,” which involves the performance of simple and routine tasks that require physical effort.

These migrant domestic workers, many of whom had very high-status occupations before leaving the Philippines, have experienced a contradictory class mobility upon migration, said Rhacel Parrenas, a professor of sociology at the University of Southern California. “They have to be subservient of someone instead of being the boss of someone.”

Plaza perfectly fits this scenario.

This story focuses on Aleja Plaza, who got a caregiving job in the U.S. even though she has five university degrees.

“I was on the top of my career,” Plaza said, recalling her life as a dean at the University of Southern Mindanao. “When you are in one city, you can always see your name there -- welcome. Then here you are,” she said.

Her world exploded when one of her students was raped. Plaza launched a series of protests against the perpetrator, who she said was the son of the mayor and threatened to kill her. She had no choice but to flee to L.A.

Upon arrival with a tourist visa, Plaza’s only option was to become a caregiver.

The median wage for home health aides and personal care aides is $10.66 per hour, which is $7 lower than the median hourly wage for all workers, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. But many caregivers don’t see themselves working in a low-paid job, especially when it is the only option they have.

“I have to find a job right away that will give me income,” Plaza said. “This is the easiest way to get a job because there are so many people who have agencies, board and care facilities who are hiring undocumented people and people with a tourist visa.”

Without a Social Security number or driver's license, she could only land as a caregiver through an agency owned by a friend. “Only people who I know will hire me,” she said.

Other Filipino workers in the U.S. often found themselves in the same situation.

“They cannot come in with a domestic worker visa,” said migration expert Parrenas. “They came here as a tourist and then transition to this job.”

A 2014 survey of 100 Filipino elderly caregivers in Los Angeles conducted by labor, advocacy and research groups showed that “40 percent of them are undocumented.” The study also suggested that the number is very likely to be underestimated because “undocumented workers were less likely to participate in the survey process due to their precarious situation.”

Among the 100 Filipinos surveyed, 61 percent had four-year college degrees, and 5 percent had master’s degrees.

The reasons why highly educated Filipinos often experience a downward mobility when they leave home are complicated, Parrenas said. The education they received in a Third World country would not be held in the same esteem as a U.S. education. In addition, the networks relied on in the job-hunting process are limited.

In the Filipino community, Parrenas said, “they meet a lot of people who do the [caregiving] work. And so it’s something that they’ll look for when they become a niche.”

To the majority of Filipino overseas workers, it is clear that they don’t get to bring their past accomplishments in their new lives. “When you go abroad, you don’t bring your qualifications with you in the Philippines,” Plaza said. “And you forget the others [achievements], because if you put them all on your resume, you are overqualified.”

Before connecting with the Filipino Worker Center, where Plaza felt empowered and learned to value her job, she was ashamed of telling others about her work and her background. “Before, I could not say I was a caregiver.” She recalled asking her children not to reveal her situation in the U.S. to her students. “I thought it was just a small-time job for people who didn't go to school.”

For years, she didn’t tell her employers or peers that she holds a doctorate, which she once considered a ticket to a promising future. “I was thinking that if I can reach the highest degree, like Ph.D. degree, then maybe I could land a good job. I could have a better salary,” she said. “But where am I now? I’m here.”

Plaza later filed for asylum and received her work permit but decided not to leave her job. “It's an extraordinary job because not everybody can do it,” she said. By volunteering as a lobbyist in the Pilipino Workers Center and starting her own insurance business, Plaza found ways to reconcile the contradiction in academic training and her job, and has since come to value her position as a caregiver more than ever.

But not all Filipinos were as lucky.

Terry, 58, who declined to reveal her last name due to her legal status, was referred to an abusive caregiving job in Hawaii in 2010 by her sister-in-law, to whom her ex-husband owed money.

“I worked like a slave,” Terry said.

Working as a live-in caregiver in a private home, Terry was asked to work 17 hours a day and was not allowed to leave home or talk to anyone else. The employer refused to provide her food and her salary was garnished by her sister in law. She went hungry every day.

At first, she relied on the cookies and cereals she brought from the Philippines to assuage hunger. Then she was forced to steal chicken breasts from the meals prepared for the dogs when she ran out of food.

“Next thing I knew I was shaking and I have to eat something-- the canned food,” she said. “I even ate dog food because I didn't have resources and food that time.”

Every night before bed, when Terry finally got off work, she would lie in bed and stare at the ceiling asking herself, “Why am I here? Why did I give up my life in the Philippines?” And the answer would always be her children.

“My life was a mess. I’m giving up my life,” Terry said. “But I'm not giving up the lives of my children.”

Terry escaped the house after 22 days and was rescued by calling 911. Since then, she has been working as a caregiver. But she experienced more abuse in a facility in Balboa Island, California. There, she worked 16 hours a day and expected to earn $90 per day, which is already lower than the minimum wage $8 at that time. What’s worse, her sister-in-law, who was later identified as her human trafficker, again garnished all her salary, leaving only $2 or $3 in their joint account.

“So I was trapped for six months, lacking food and money,” Terry said, adding that she left the job after her visa expired.

Now, she has been in caregiving for six years. She said, during these years, supporting her children's’ needs and paying their school tuition have been the biggest motivations for her to carry on.

“School matters,” said Terry, the mother of six. “I believe if I can achieve my plan to help my children, they’ll be able to pursue their dreams [and] to level up.”

But can education really secure their future and promote upward mobility?

Hear What They Think of Education

“It is one of the biggest ironies, right?” Parrenas said when speaking of how highly educated parents still believe in education after ending up as domestic workers themselves.

When they send their children to school, “the kind of mobility that they want to achieve for their children is that maybe their children can actually go do a job other than domestic work,” she said.

“So if their daughter becomes a store clerk in Dubai or a factory worker in South Korea or a factory worker in Taiwan, for them it's like a huge jump in mobility,” Parrenas said.

The stigma around domestic work is deeply rooted in the Filipino community. Even Terry, who considered her job respectable, would rather her kids not follow her path.

“I wouldn’t encourage them, not even to start and try it,” she said. “Because if they do, they would tend to forget what their educational background is. I want them to explore more. I want them to do something different. I want them to do something courageous, something they can be proud of.”

Terry plans to bring her youngest son, who is now 17, to the U.S. if her human trafficking visa is approved in the future. “But maybe start from the scratch or take another degree here,” she said.

“I told him that ‘even [if] you finished college, you have a degree, it’s nothing to the company that you are going to apply for,’” she continued: “Because when you get here it’s different.”