It's easier to run

Replacing this pain with something numb

It's so much easier to go

Than face all this pain here all alone

Sometimes I remember the darkness of my past

Bringing back these memories I wish I didn't have

Sometimes I think of letting go and never looking back

And never moving forward so there'd never be a past

- 'Easier To Run', Meteora (2003)

Linkin Park's lead singer Chester Bennington often sang about the demons he battled in his mind. His songs seemed to pour out from a deep well of boiling emotion, touching upon feelings of despair and simmering anger, rebellion and suffocation, depression and the urge to end it all.

But when the 41-year-old rocker was found to have killed himself this July, only months after another famous rockstar, Soundargarden's Chris Cornell, hanged himself to death, and the same year the popularity of Netflix show '13 Reasons Why' had brought the issue to the forefront of public attention, many began to call suicide an epidemic.

But the truth is, suicides in the US were already rising at an alarming rate for years. And experts have been quietly pointing this out.

In 2016, the suicide rate rose to a 30-year high in the United States, according to a federal study that pointed out that this surge had taken place despite a continuous drop in the country's overall mortality rate. Suicide is now the tenth leading cause of death in the country. On average, 105 suicides take place everyday, which means there is one death by suicide every 12 minutes.

0

Americans have already killed themselves today

One November day in 2010, 18-year-old Adam Askenaizer sat alone in his dorm room, lining up Tylenol pills on his desk. He arranged them carefully, meticulously, giving no outward sign of the anger and despair that drove him. Then, one by one, he began to swallow them.

To this day, he can't remember how many he took before he called his mom to tell her what he did. What he does remember is the ambulance that came to take him soon after, the stretcher, the overpowering smell of death in the psych ward he was locked into until the next day - and the sense of euphoria he felt when he stepped out free in the morning air and realized he'd survived."

That feeling has stayed with him, even seven years later as a grad student at USC when he feels far, far from that day. "If you're unaware of other possibilities or other paths for your life, then you feel like the only way to escape it is to kill yourself, that's the only way out," he says.

"But there's so much to learn and explore and experience in life. You just have to realize life has an infinite amount of directions and there's so many new beginnings just waiting for you and you can't just deny yourself the agency or the ability to pursue them."

Askenaizer was a new student at the University of Tulane in New Orleans when life began to sour for him. Soon after he enrolled as an undergrad, he began to feel a growing disconnect with his program, his university and all his peers.

"Slowly I came to just hate it. I hated the place, I hated the school, I hated the city, I hated the people. I just really felt like I didn't belong there."

And that hatred, he says, turned inward, until he began to feel angry and hopeless and like he had wasted his life.

"I just felt kind of trapped. I felt like my life had no direction. I felt like I was a fuck-up. I felt like basically my whole life was leading up to this big mistake and I didn't know what to do. So I took a bunch of pills."

Askenaizer was not alone. A study published by the National Institutes for Health exploring the link between suicide and hopelessness found that it was among the most dangerous warning signs for a future attempt. When people began to feel like they were trapped in their situation and gave in to despair, they were likely to try to end their lives - more likely than those who were suffering from depression or other mental illnesses.

It was only after he came a hair's breadth away from taking his life did Askenaizer decide that a seismic shift was in order. He returned home and decided to find out what truly interested him and today, he says, he's glad he lived to see how far he's come.

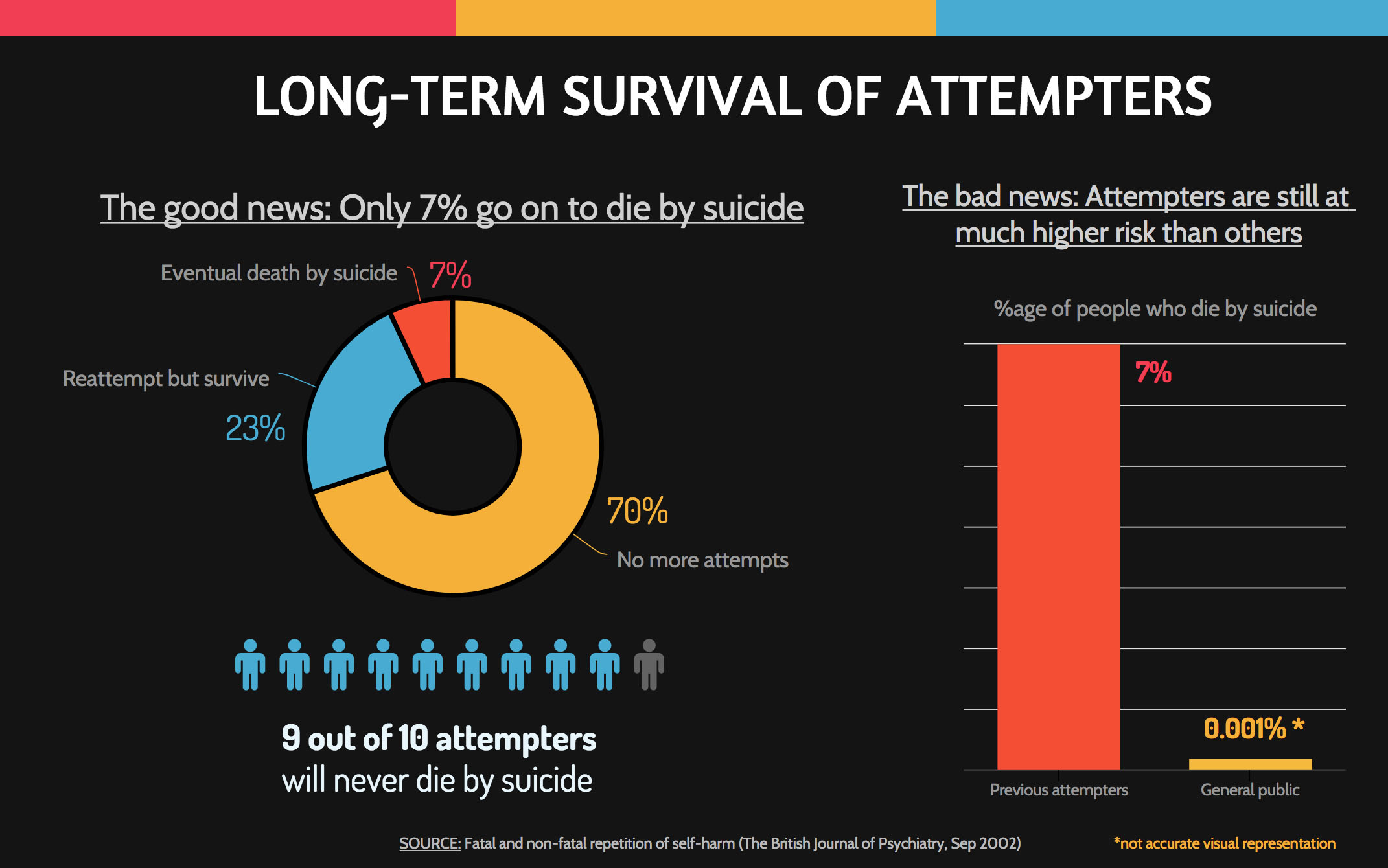

For most people, a suicide attempt is part of only a short-term crisis. According to a literature review of 90 studies published in the British Journal of Psychiatry, seven out of ten people who attempt suicide and survive go on to never make another attempt. But the underlying risk factor - for example, depression, as was the case with Askenaizer - needs to be paid attention to and may sometimes lock attempters in a lifelong struggle with themselves. And sometimes, it may also lead to another attempt. Despite the low rate of recurrence of suicide attempt, a history of such an attempt remains one of the strongest risk factors for suicide. Studies show approximately 7 percent of those who attempted suicide and were then treated in a hospital did go on to kill themselves later in life.

And that is why Askenaizer doesn't take his happiness for granted. He says he's in therapy and is still dealing with the underlying mental struggles that prompted his suicide attempt.

"I still have a lot of issues. That whole time in my life, I don't feel like I've fully escaped it yet because sometimes it kinda reoccurs and I get really depressed. But I think I'm more equipped now to overcome it. I'm stronger now. And I can remind myself more easily that I have a support network of people. It's more evident that there are people that want to help me and that care about me."

A supportive network of people to share your struggles with, whether in a family or a community, is important, says Tory Cox, an expert in crisis intervention and suicide and a clinical associate professor at USC. Cox says experts like him who intervene in life-or-death situations understand the value of having people to share pain with and fall back on during stressful times in keeping people from the edge.

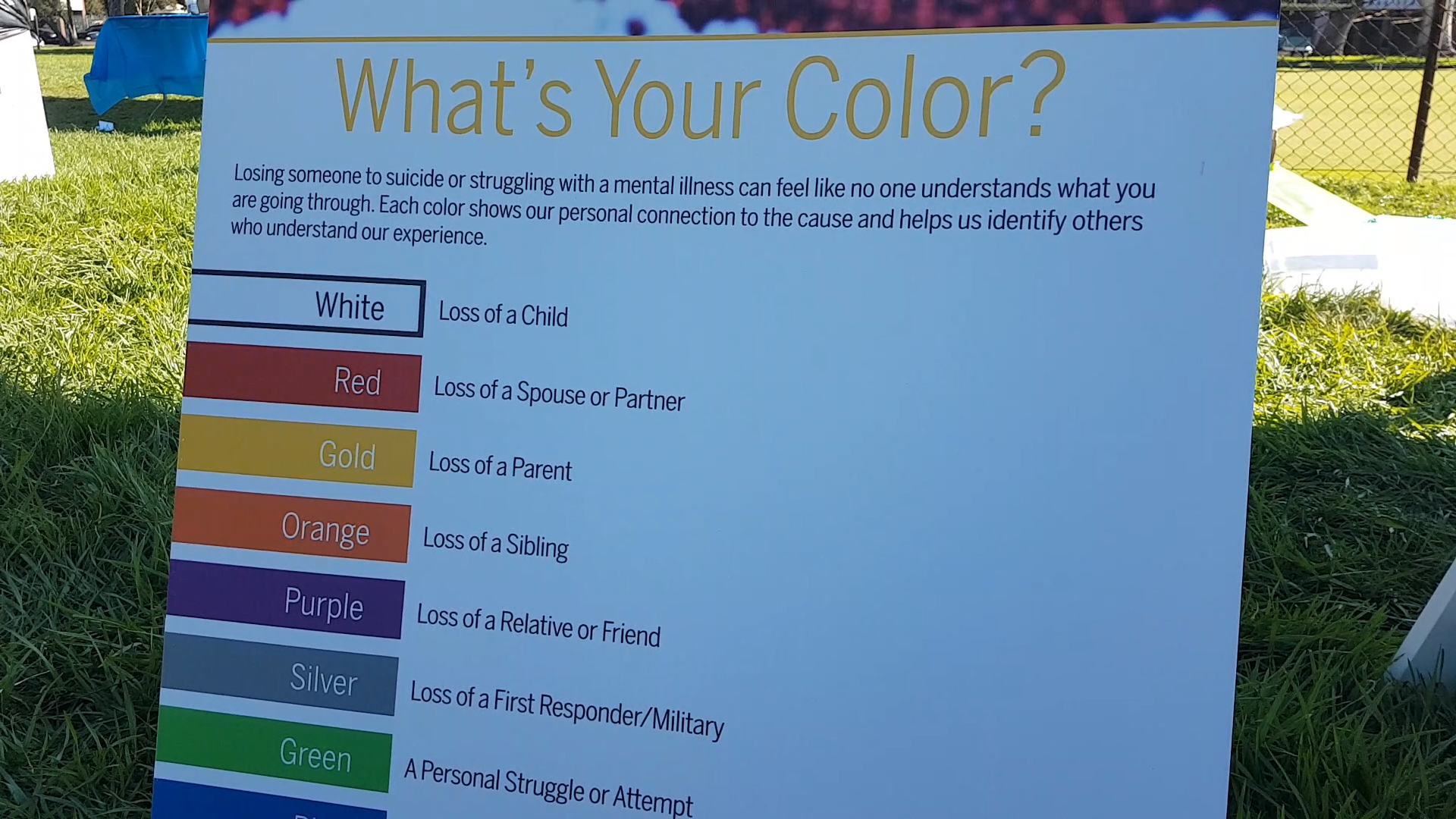

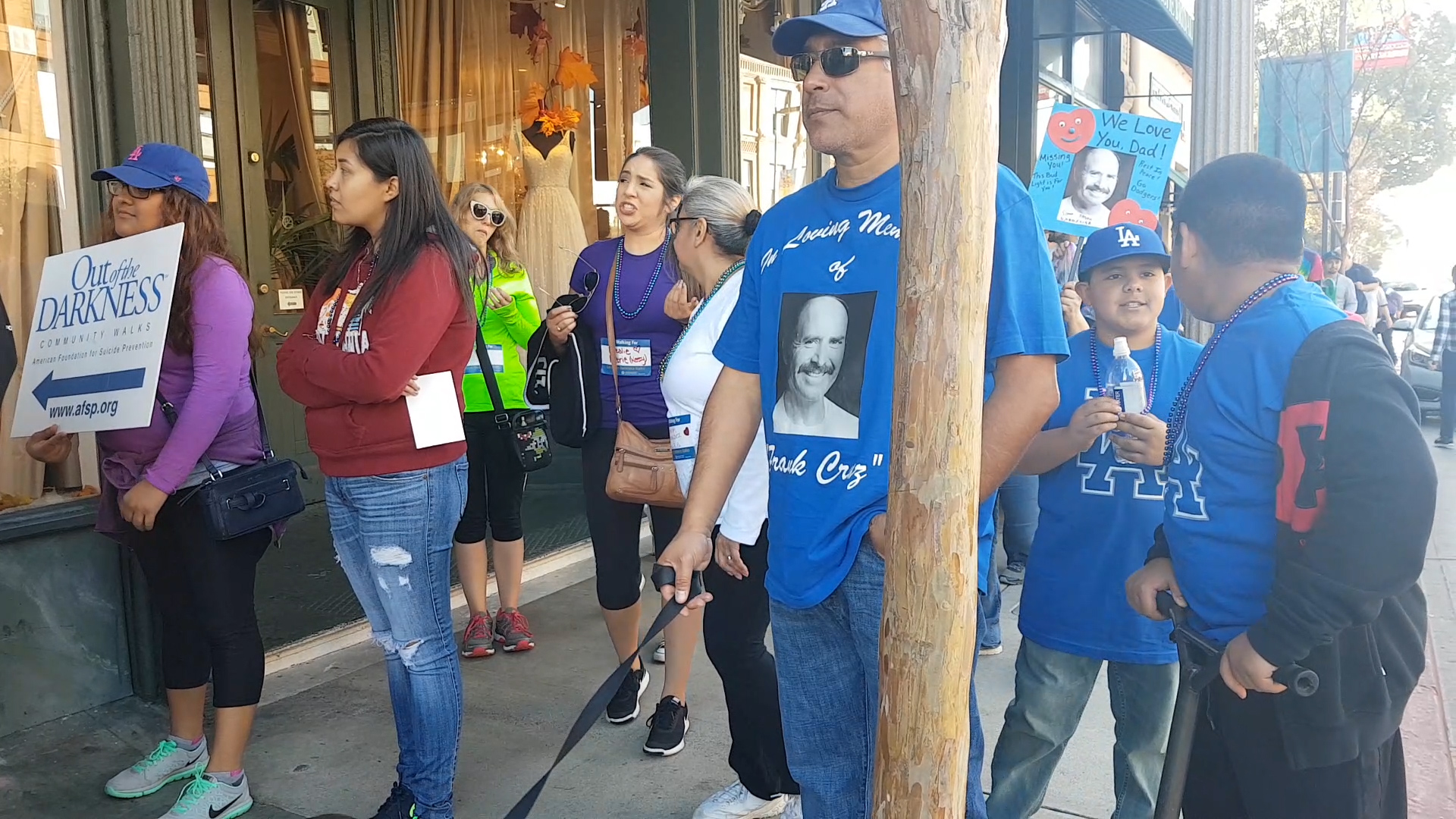

But for those who don't have such a community, several local and national organizations offer support groups, gatherings and helplines and organize events specifically to address the growing need for suicide prevention and counselling - for both those who have personally had a brush with suicide or suicidal thoughts, and for survivors of suicide loss.

Anne Marie Ankers, a board member of the Greater Los Angeles Chapter of one such organization, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP), says the AFSP organizes walks, survivor day events and seminars to give a voice to people who cannnot talk about their pain because of the stigma surrounding suicide. "The biggest thing is making the connection between people and getting help," she says.

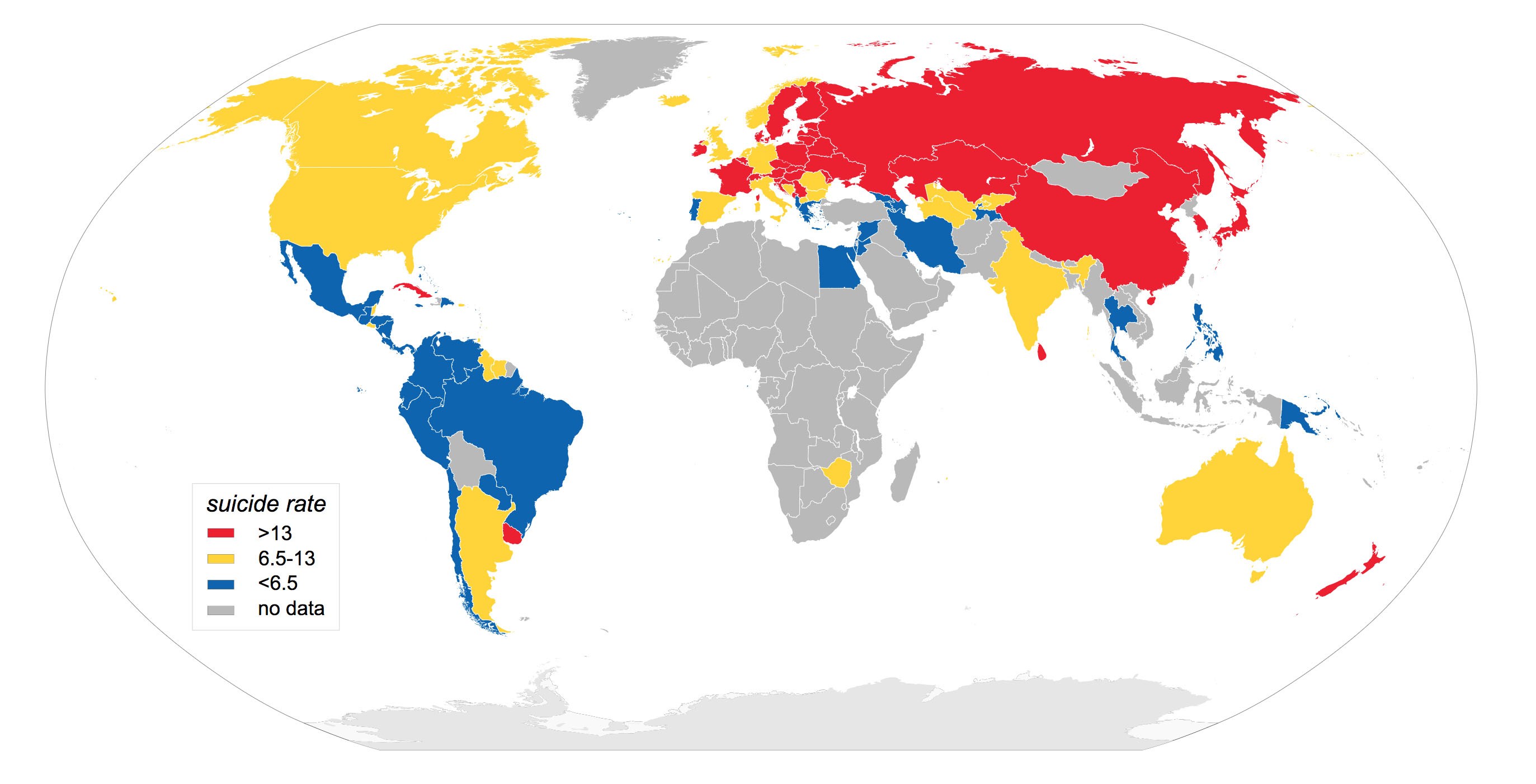

But not everyone has access to these resources. 27-year-old Kriti Sharma, who was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and clinical depression after her first suicide attempt in the tenth grade, is in India, a country with the highest suicide rates in the world and where services for suicide and mental health are not as widespread or well-funded as in the US.

Sharma went on to make several more attempts, once taking 36 different pills that damaged her kidney, at other times jumping in front of trains and trying to cut her wrist with a knife.

"What makes me try is some sort of emotional trigger," she says. "It was my parents' dysfunctional relationship earlier. And it's mine now. And I've seen some stuff in my life, lost people I loved. I'm still processing those things.

Sharma says she knows there are people around who care about her, but she prefers not to tell anyone what she's going through because most don't react well.

"I have discussed my depression, but not suicide. It makes me feel as if people will consider me stupid. And that whole lecture about life being a gift and fighting the good fight - I never want to hear those things. They're just the same generic inconsequential comments."

How To Be The Support Network

Unlike Sharma, most people who attempt suicide usually reach out for help in some way. Daniela Zanich, an expert at the Didi Hirsh Mental Health Services, Susan Lindau, an expert in mental health for severe cases, and Tory Cox, an expert in crisis intervention and suicide, give expert tips on what you must do if faced with such a situation.

"When I feel suicidal, I just feel a tightness. I know I'm not alone, but at the same time I know I cannot explain myself to anyone. I feel very lonely. There's this looming sense of uselessness and hopelessness. The constant question: 'what even is the point?'. It's all-consuming. Logic and rationality stop functioning. It's as if something else almost takes over."

Sharma says she's made great progress now in dealing with these feelings and with her sense of isolation, with the help of friends and family and by seeking professional help.

"I used to think therapy was stupid. But I reached a point where I was so alone, I was ready to pay someone to just listen to me. That was the big breakthrough for me. I've been going to a shrink for more than two years regularly now, and I have a better understanding of why I feel the way I feel. I'm learning how to process emotions."

Now, she says, even though she often goes through hard days when her emotions threaten to overwhelm her again, time, support and therapy have enabled her to deal much better.

"Now when I get angry, I put that energy into something else. I prefer staying quiet and giving myself time to really think through things. I recently quit my job after being overworked and sick for months. Today, I had nothing to do all day and a couple of hours ago, I felt like breaking something. I made a henna tattoo instead."

Susan Lindau, an expert in mental health for severe cases, says distracting yourself or making yourself hold on to life for just another 20 minutes is often enough to let the worst of the crisis pass. "Neurobiologically, the amygdala gets triggered and all you have is this excruciating fear - the fight or flight - going. And with that intense pain, all you can think about is getting out of the pain. I also describe that as 'brain freeze'. There's no clarity, no thinking. But 20 minutes is how long you're going to feel like the only option is killing yourself. But as you sit and talk, sit and breathe, you come back to feeling a little more grounded. You might not feel happy. The depression's still there. But now you can say 'I feel horrible and I don't have to kill myself.'"

Today, Kriti Sharma says she has come far in understanding how to deal with her crises. Even though she is still struggling with her mental health, she says overall she's "in a good place". She has a job in advertising, she's married and she recently moved to Chandigarh, which she calls one of the better cities in terms of health in India.

According to the World Health Organization, the majority of suicides occur in middle- and low-income countries such as India, where access to mental health resources is limited for those who don't belong to the highest rung in the socioeconomic ladder. Worldwide, almost 800,000 people kill themselves every year - one person every 40 seconds.

But you don't have to be from outside the United States to be at greater risk and be deprived of the means of seeking medical help due to your socioeconomic status. For 32-year-old Remington Hayes, a support network and a caring healthcare system always felt just out of reach.

Hayes says he spent his childhood feeling abandoned by a neglectful father who was sometimes in prison. Because he is mixed-race and didn't quite talk and dress like others at his school, he was rejected by his peer group as being "not black enough", which he says contributed to a feeling of worthlessness and isolation throughout his life. Later, it extended to his relationships. Every time one would fail, he'd be caught in the same spiral of self-loathing, he says, until he'd be pushed to the edge.

"I was like, 'ok, why should I stick around? There's no one who gives a shit about me.' I won't have to deal with any of this any more. I won't have to wake up. I won't have to feel feelings. It felt comforting, the idea of dying."

Hayes attempted suicide four times, trying to burn, hang and poison himself, from ninth grade upwards. Depression descended upon him on and off. He tried therapy a couple of times, but this was before Obamacare, and it was too expensive to keep going for sessions.

What pulled him through was a different path to healing - the therapy of the mosh pit.

Mosh pits are areas in front of the stage at rock concerts where fans can express the rush the music gives them by dancing energetically, often bumping and jostling each other. They were where Hayes discovered the heady feeling that inspired his love for 'metal' music.

"I had grown up thinking men don't cry or show emotion but love and anger. Metal helped me feel like my emotions outside of just anger and love were valid too. That crying was ok too. And I found immense strength in simply allowing myself to cry. It kind of became my own personal rebellion against everything people told me about 'being a man'."

The power and raw emotion of metal bands like Slipknot, System of a Down, Korn, and Machine Head were a kind of catharsis that gave him the strength to fight his urge to kill himself. The idea of giving up was no longer acceptable.

"I couldn't cross that line. I had to throw one last punch, even if it meant suffering through another few years of monotony and feeling terrible."

But for Hayes, what ultimately helped lift him out of his emotional funk was the news of Chester Bennington's suicide.

"Chester's death hurt because he was the voice of a generation. And recently I learned he had felt the same way I did, suffered from depression the same way I did. And the thought that he could be so successful and so loved and make it to 40 years old and still kill himself, it hurt on all sorts of levels. Mostly though it's because I saw that even with all he could ever have, if he got too low he could still lose to depression, which means I could too. And since I was so close to actually doing it, I saw myself in his death and I really think that's what began my ascent out of my depression."

Not long after that, Hayes found a job working with specially abled children at high schools, work that gave him purpose in life. And he fell in love. Is it a happily ever after? He doesn't know.

"But I feel like there's so much more promise in my life. Had I done what I wanted to, I wouldn't have met her or been working with the kids. Those are the two biggest reasons I am so very happy to be alive."

Twenty nine-year-old Alison Lee (name changed) had her own brush with suicide seven years ago.

Her roommate in graduate school had a fractious relationship with her. A minor misunderstanding escalated until the rooommate got all her friends to gang up and bully Lee mercilessly. "They started to catcall me - say mean things out loud as I passed by. They started spreading rumors about me, and began to turn my friends away from me by spreading lies. I felt attacked from all sides and I couldn't do anything about it," she says.

"I completely slipped into a depression. I had nightmares, so bad I didn't sleep for days. And even when I did I'd wake up screaming and crying. I had smell triggers. And I completely gave up. I stopped eating or bathing."

One day, she couldn't take it anymore and was seconds away from stabbing herself or fatally slitting her wrists with a knife she had in her dorm room. Her boyfriend at the time (now her husband), who was on the phone with her, somehow forced her to throw the knife away.

Today, Lee is far away in life from the powerlessness she felt in her grad school days. "It's funny to look back, you know, standing where I am today. I have a job, I have hobbies, I'm married to my best friend and the absolute love of my life, and we're going to be parents soon. I cannot believe I almost ended my life for something so insignificant in the long run, and I almost gave up the most amazing life I have now."

She says that not only is she glad she survived her suicide attempt, but that she's grateful for the experience.

"I have never tried to suppress those memories. That is what makes me who I am, and that's a large building block in my life. I'm proud to have been a survivor. It made me a stronger person - I can sort the big stuff from the small now. And it's taught me a few things. That there is a light at the end of the tunnel and even if you can't see it, you must believe with every fiber of your being that it's there. And that it's okay to fail. It's not the end of the world and certainly not the end of you. You can try again."