Talking about race and ethnicity is messy. Talking about whiteness is uncomfortable.

Threats from Washington D.C. to build "the wall" or white supremacist rallies across the nation from Charlottesville, Va., to Anaheim, Calif. highlight race and issues like police brutality or systemic racism and privilege.

President Trump's speeches and calls to "make American great again" speak to racist and intolerant views some Americans hold that are still very much part of the present, no matter how much others would like to believe them to be part of the past.

For some, the issues between white people and people of color are on their mind all the time; not because they're "woke" or even particularly interested in politics, but because it's in their blood.

It's in my blood. My dad's family is Japanese and my mom's family is Polish.

Multiracial young people are a quickly growing demographic in the United States.

In 2000, the U.S. Census added "two or more races" to the race category. A U.S. Census report in 2016 put the number of self-identifying multiracial people at 10.4 million, or 3.2 percent of the total U.S. population.

I think identity is complicated. I boil down my understanding of my own racial and cultural identity into four categories.

I am biracial, the "two or more" option. I identify as or feel closer to Asian. I am connected most closely to my Japanese culture but do feel that I have cultural ties to my mom's Polish roots.

There is how you identify on forms — which can be different from how you identify or feel internally. I am biracial, the "two or more" option. I identify as or feel closer to Asian.

There is how you identify culturally. I am connected most closely to my Japanese culture but do feel that I have cultural ties to my mom's Polish roots.

And lastly, how others see you. That's me, on the right, at about age three. What do you think?

I will ask others how they see me.

So what is it like to be multiracial today, including navigating awkward situations and daily interactions or dating? What do you think about your whiteness?

In the following text and short videos, five mixed-race millennial women give a glimpse into their experience and how the world interacts with them regarding their race and their thoughts on white privilege. All of them are half-white, and each of them has their own opinion of how they fall on the spectrum of white to person of color — both to themselves and to the world.

Whiteness is omnipresent. Self-identity shapes how you move through the world. If you're racially ambiguous how does that affect your opinions of white people and white privilege?

It's hard to have a conversation about race with anyone, not just white people. Maybe a good place to start is with those who bring white people and people of color together as one.

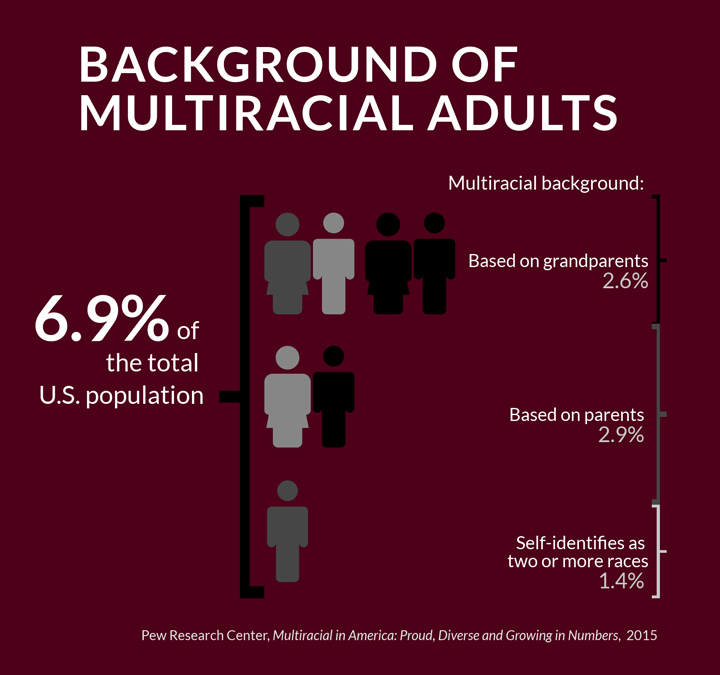

In 2015, the Pew Research Center surveyed the attitudes, experiences and demographic characteristics of multiracial adults.

The survey, Multiracial in America: Proud, Diverse and Growing in Numbers, categorizes participants as mixed race by their genetics, going back to their grandparents' generation. If at least one of them is not the same race as themselves or their parents, they were classified as multiracial.

Pew estimated that in 2015 6.9% of the total population was multiracial, though the U.S. Census Bureau reports that roughly 2% identified themselves that way at the time.

This difference between being of mixed-race and identifying as such is what the Pew Research Center calls the "multiracial identity gap."

Over half of those who are mixed-race don't consider themselves multiracial. Pew found that this 61% of people have different reasons. These reasons can include that they look like one race, were raised as or closely identify with one race, or they never knew the family of the different race.

Pew also found in the 2015 survey, women outnumber multiracial men by 61% to 39% in the adult multiracial population. This is significantly different from the general U.S. population, as the share of women is 52%.

The five women here do not all identify as multiracial, though they all acknowledge they have multiracial backgrounds.

Please click on each portait to see photographs of her parents and learn more about her racial identity.

26 years old. Redondo Beach, Calif.

24 years old. Los Angeles, Calif.

25 years old. Los Angeles, Calif.

24 years old. Huntington Beach, Calif.

26 years old. Anaheim, Calif.

Multiracial Americans are at the cutting edge of social and demographic change in the U.S. — young, proud, tolerant and growing at a rate three times as fast as the population as a whole.

These five women also represent some of the multiracial identity gap. Two of the five identify as one race; the other three identify as multiracial but on a sliding scale: they lean white, usually lean Asian and biracial, respectively.

Research institutes, experts and many multiracial people themselves use the terms mixed-race and multiracial interchangeably. The same is true for this article and interviews.

California is more diverse than the United States' average. In the 2015 Census Bureau's estimates, just 3% identified themselves as two or more races nationally, but California reported 4.5%.

Pew found that mixed race individuals are more likely to cross racial lines in their social and romantic lives. A diverse community is easier to relate to than one that is all of one race, especially if you feel like you don't necessarily fit neatly into one racial category.

Pew found that mixed race individuals are more likely to cross racial lines in their social and romantic lives. A diverse community is easier to relate to than one that is all of one race, especially if you feel like you don’t necessarily fit neatly into one racial category.

The Role of Gender, Class, and Religion in Biracial Americans' Racial Labeling Decisions, a study by the American Sociological Review in 2016 focuses on the effects of gender, socioeconomic status and religion on racial identification. It cites previous studies and surveys that show gender and socioeconomic status are highly correlated with racial identity, called "the original trinity of intersectionality."

Many of us have heard of the original trinity, but I'm choosing to focus on race through the lens of gender. I think inspecting the two points — gender and race — of the intersectionality trinity is a good way to open the conversation to understanding the mixed-race experience.

Socioeconomics are brought up as they relate, or don't relate, to white privilege.

According to this study by the American Sociological Review, men and women approach race and ethnicity differently. Research suggests race is less malleable for men.

The nature of racism in the United States shows men of color experiencing substantially more discrimination than women of color. Negative interactions with people who perceive a multiracial man to be a person of color prompts the man to embrace this identification.

Physical attractiveness is a more important resource for women. Lighter-skinned women are perceived as more desirable or more represented in the media, for example.

I believe this "colorism" — or treatment within your own community based on the shade of your skin — applies to the multiracial community too. But the sample size of this project is so small and all of the women, including myself, look the same with relatively light skin and dark hair, that I decided to leave colorism out too.

"Yes... I would say I identify as a person of color," she says. "I identify as Mexican-American. At school, I definitely identify myself as being Latina because I think that it's really important for the Latino students to have a role model."

Chase, who has a white father and Mexican-American mother, says it was as she got older that she started to think about what it meant to be Mexican-American and the unsaid things that come with it.

"Over time you become older and understand like, because of this heritage, people are going to view me a particular way and people are going to assume certain things about me," she says. "It becomes more political as you get older."

But because of her mixed racial background she feels that she can empathize with people more easily because she's probably had a similar experience from the perspective of one of her two races or families.

When I as applying to colleges there was no bubble and I was like, 'Why am I an outsider?'

"They finally added a bubble on tests that says circle one or more [races or ethnicities] that you identify as, so that's nice because that used to be a struggle," Chase remembers. "When I was applying to colleges there was no bubble and I was like, 'Why am I an outsider?'"

Haley Matsumoto is relatively flexible with how she identifies on forms.

"I'm quite a few things," she says. "Everyone [in my family] is mixed."

Matsumoto has her boxes picked out. She says the "two or more" one is the one she checks. Otherwise she will check Asian/Pacific Islander, white or other. Her default is two or more, though.

She prefers Asian, if she had to pick a race with which to most strongly identify.

With both Chase and Matsumoto, applying to colleges and deciding on a race to select was difficult.

There's talk about affirmative action and while some people automatically fall on one side or the other, those who are mixed race with white can decide how they want to identify to schools.

"What made me feel better in school when I was applying for colleges was that they don't know what two races," Matsumoto says. "I could be black and Asian and there doesn't have to be any white involved and they wouldn't know. I always hoped I wasn't getting anything because of white privilege but because I was good at what I do or qualified."

Chase used to feel kind of guilty for checking Latino. She knows it sounds better to schools looking for diversity.

"I used to feel like, 'I don't know, I'm only half…' but then I decided the spot that I'm taking in college or a job is probably from a white person and not a person of color," Chase says. "So even if I inch part-way with my half-Mexican-self, I still upped the diversity and probably didn't hurt someone else of color."

Being multiracial is kind of like getting the best of both worlds, according to Lizel Shoup, whose maiden name is Mooney. She says it's like getting an access pass to white experiences and, in her case, Asian experiences too.

"It's just more spice to life," Shoup says.

The half-white-half-Filipino 24-year-old has natural dark-red hair and freckles, both of which she attributes to her dad's Irish roots.

"When I was in fourth grade we had to present our culture and our heritage in front of the class," Shoup says. "I was going to present on being Filipino. You had to bring a dish or something else to represent your culture. My mom had passed away, so I went home and told my dad and he said, 'Well why are you presenting on being Filipino? You're American; just bring hot dogs or something.'"

Shoup says this was one moment that she felt there was a part of her that was more than just American. Her mom was born in the Philippines and she knew that was a part of her.

Growing up on the border of Orange County with a white dad after her mother died, Shoup feels that she identifies more as white.

With no Filipino influences in her young formative years, she believes this definitely affected how she "turned out."

Sometimes Shoup feels awkward because she says she doesn't know more about her culture than the stereotypes about her mom’s side.

Chantel Buchi believes she looks white, but also passes as Hispanic.

"I think to most people I do come off as white," Buchi says. "People forget I'm half-Peruvian. They'll always just think of me as white, I think."

Buchi has been to Peru to visit her family understands the culture and identifies with it too.

"I'm happy I’m not pure white," she says. "I feel like sometimes they get a hard time. I like the fact that I can say I'm Peruvian. Most people can't even say they've gone out of the country and I've been to Peru 12 times."

Buchi thinks that another reason she passes for white is because she doesn't speak Spanish. There aren't any queues that she is Peruvian. She doesn't cook Peruvian food either.

"My culture is white."

She says Utah is not very diverse. She makes a point to say they're great people, but they are mostly white and not many Hispanic people live near her in Salt Lake City.

"If I had been around more Hispanics, I would have gotten into eating and cooking more Peruvian food and not being so Caucasian, I guess."

She feels that she has a broader understanding of life because she has been to another country and another culture. Even though she identifies as white and most people see her as white, she feels like it's gotten her out of her comfort zone.

The way that others perceive you is sometimes different than how you see yourself, or how you wish others would see you. These women have a racial identity they have chosen to own. Like Ramirez, some of these women feel one or both races but present to the world as another.

Haley Matsumoto prefers Asian-American but says she usually gets guesses about her race that are all over the map. It seems like it's never a natural question to ask.

But she's used to it "anytime, anywhere" from strangers at her job or coworkers.

"The approach is, 'What are you mixed with?'' Or they'll go straight into it like, 'Are you Asian, are you white?' and just start asking,"" she continues. "But it all comes back to questioning your ethnicity."

Matsumoto's little sister's response has always been "I'm American" with lots of attitude and ends the conversation.

I had someone accuse me of pretending to be Asian - of taping my eyelids so I wouldn't have the white look or something.

Others do see Matsumoto as Asian, but maybe not in the most sensitive way.

"Someone bought a hat that had like an Asian-looking girl on it and he was like, 'Oh, I got it because it looks like you.' And she's just got these little lines for eyes. Like, that’s pretty racist, friend."

Laura Chase, who identifies as Latina, thinks she looks racially ambiguous.

The perils of first impressions and dating apps

"I have people ask me very frequently, 'What are you?' I think I look racially ambiguous so they ask me all the time," Chase says.

She brings up an anecdote about dating.

Ramirez struggles with identifying as biracial-Latino not being able to do what she thinks is a big part of Latino identity — speak Spanish.

When people do learn her name is Ramirez, much of the time they do speak Spanish to her and most of the time she can't keep up.

"It's embarrassing," she says. I think it makes you question if you have the authority to own that identity."

As a white-presenting person, it's not a challenge for people to treat her as white. It's hard for her to think that she and her mom go through life with a different experience than her dad based on the color of his skin.

"Just the awareness of that makes me kind of protective of my dad a little bit more," she says. "I don't think people are fair; I want people to be fair to my dad because I know he's the same as everybody else."

The spectrum you can fall on of white person to person of color is wide. Each multiracial person's experience is different. While these women fall relatively close on the spectrum, they each have unique interactions with the world.

Liz Ramirez talks about her views on white privilege and her own whiteness.

Ramirez identifies as biracial now. She feels that she grew up in a culturally white household and always thought she was white but knew she had this other side. As she's come into her own identity, Ramirez says she's felt a much stronger connection with her father's heritage and is now choosing her own identity.

Passing:

"I present to the world as a white person," Ramirez says. "But how I identify internally — I identify more with resistance movements and minority causes. I think there's always a little struggle to decide, 'Do I identify with what people are going to view me, or do I identify with the things that I believe in, and kind of this other side of who I am?'"

What is white-presenting?

White-presenting is other people reading a person as white. This is without this agency and self-determination of an individual.

Ramirez says she'd like to have some melanin in her skin. And that while she does tan — it takes some work — having such "pasty-white" skin makes it hard for people to believe she could be anything but white.

"I pass as white — but I try not to [pass]," Ramirez says.

In some communities, "passing" is a form of privilege, safety or power. A person can pass when it comes to sexual orientation, gender or disability. In the case of whiteness, in a white world, one does receive benefits from looking white.

Whenever conversation nears the topic of race or anything Ramirez could comment on her own identity, she makes sure to tell them she's biracial.

"It's important to me to own that space and bring my identity with me," Ramirez says.

Privilege:

Ramirez is aware she could be a "fly on the wall" in white situations.

"The most important to me is to infiltrate white spaces with a minority opinion, or with people of colors' interests at heart, because while there's a lot of racism all over the place, I think what white people say in the comfort of white people is different than what they'll say in the presence of anybody that's non-white," she says passionately.

"I think it's important to almost… violate it," Ramirez continues. "I feel a responsibility to bring up issues with white people because they're not always forced to talk about it. They don't have to because they're safe. I don't think you can get [this experience] unless you present as white. People will let you in and you can use it as a teachable moment."

White privilege is the advantage that white people get while navigating the world. It is not personal, but systemic. White is normal, neutral, and ideal.

A good place to start studying white privilege is Peggy McIntosh's famous 1989 essay, "White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack." She examined her own white privilege and encouraged other white people to examine their own and ask themselves what they will do to end it.

McIntosh is a scholar at Wellesley Centers for Women. She examined male privilege and realized that just as men who don't believe in their male privilege, as a white woman who was ignorant of her own privileges she was being an oppressor to women of color.

She numbers daily privileges that she can most directly connect to her skin color rather than factors like class or religion.

Privileges like:

"I do not have to educate my children to be aware of systemic racism for their own daily physical protection.""I have never asked to speak for all the people of my racial group."

"I can remain oblivious of the language and customs of persons of color who constitute the world’s majority without feeling in my culture any penalty for such oblivion."

McIntosh calls white privilege "in invisible weightless knapsack of special provisions, maps, passports, codebooks, visas, clothes, tools and blank checks."

Profit:

Ramirez says that anyone who passes for white benefits from white privilege. It would be foolish of her to say she doesn't also, but she would like to think she doesn't take advantage of it.

"I think it's important to use the white privilege you have for good," Ramirez says. "I think there was a great call for white people to come out and stand on the frontlines [of protests] because your body is so useful as a tool to get other white people to listen."

A simple google search of "white ally" retrieves both thoughts along the lines of "dear white people, do better now" or "here are some ways to do better."

It seems Ramirez has a foot in each camp.

"There are some white people who don't care about black people's bodies, they don't care about black people's lives, they don't think black lives matter," she says. "As an ally, you have to use the benefits that you receive to fight for the causes [in which] you believe. Not necessarily going out and standing on the frontline of everything, maybe that's not your speed, but just doing something positive."

It's obvious Ramirez is aware that as a biracial person who is written off for white she holds a great amount of power — a great amount of power in society.

There are reasons a person may or may not identify as mixed-race. Some, like Ramirez, are afforded the privilege of being able to choose how they identify.

For example, studies, including the Pew Research Center's survey and the American Sociological Review's study, show that multiracial people who have more negative race-related experiences tend to identify with their minority race. The multiracial group who has the highest reporting of being treated badly because of their multiracial status is black-white, while the least is white-American Indian.

Ramirez knows she doesn't have to face a lot of the injustices and inequalities that many who darker-skinned like black-presenting would.

"I'm afforded the luxury — the white privilege — to just live my life as a white person and I can choose my own culture, identity and race, and try to use it in beneficial ways."

Is society more accepting of race and culture?

Félix Gutierrez

Félix Gutierrez is a professor emeritus of journalism at the University of Southern California's Annenberg School of Communication and Journalism. He spent roughly 45 years focused on issues of race, ethnicity and other aspects of diversity as they relate to the media, margins of society and communication within communities.

He thinks of the concept of multicultural is "multiple cultures" — that someone will have different and sometimes conflicting cultures; picking and choosing what they want.

The blending of cultures is based on individual choices. But it wasn't always like that. The native Southern Californian remembers what it was like growing up in East Los Angeles and then white South Pasadena, being one of three Mexican-Americans in his graduating class.

"White privilege, that's the world that I grew up in. It's a white standard. They made a system," Gutierrez says.

"The traditional approach was we're all somewhere on the road to becoming white," he says. "American was the term that was defined as white. So you have African-American; we were called Mexican-Americans. Part of you were Mexican and then you were transitioning over here to being Anglo."

Anglo is the term they used for "white people." Gutierrez says the transitioning to white society idea came out of immigration from Europe. People were all fair in complexion and could forge a new identity in the melting pot.

"But certain groups because of look or because of geographic differences, we didn't come from Europe. An Asian-American person could change their name but they're still going to look Asian, a black person's still going to look black," he says.

Mexican was a kind of a bad word. But it was our word. It's who we were. And my parents were very proud of being Mexican.

Society was still regulated by white people who proclaimed all men are created equal Gutierrez says. He and other minorities believed that if you worked hard and lead a good life you would rise up and succeed. There were examples for women and minorities. The difference, Gutierrez says, is that the exception was shown as the rule.

Gutierrez attended college at Cal State L.A. in the 1960s. He remembers watching the integration efforts in the south and riots for civil rights.

"Here, people of all cultures could go to college and we could show what we could do. But for us the barrier was at the employment level," Gutierrez says.

When Gutierrez interviewed for Northwestern's graduate journalism program in the 1960s, the interviewer asked him the "What are you?" question that so many mixed race or ethnically ambiguous people are frequently asked. Even if the context for the question is different now, the awkwardness is the same. Gutierrez did attend Northwestern.

"Everybody was trying to adapt to the white norm — if you showed you could make it in a white world you could be a success, Gutierrez says. "It was always you're Mexican but you overcame it. But that was the integration goal — that we integrate to become white."

He thinks society values other cultures more now. They've always been proud of who they were, but now white people are learning and benefiting from it too.

Gutierrez says that interracial marriages were banned in some states when he was in college and at Northwestern.

In 1967 the U.S. Supreme Court's rule on Loving v. Virginia overturned all anti-miscegenation, or interracial marriage, laws.

The neighborhoods are much more integrated than when Gutierrez was growing up. He thinks we're all better when we know more than one language and live with more than one culture.

Multiracial young adults are embracing their cultures. The road many millennials are traveling might not be the white one.

"In a sense, [racial identity] is a decision and a choice that you can always make. But it's also a decision people can make about you. And that might not be the one you would make [for yourself]."

Gutierrez thinks that cultural decisions are more important than your racial make up. While race is more visible, it doesn't determine how you behave and where you go.

"It's really up to us to decide who we want to be. We don't have to forget who we've been in order to become who we want to become."

Me, 1991.

I wasn't aware of race when I was really little.

Eventually we all become educated about race and society. And I wanted to be like the white people. They just had something that I didn't.

As a little kid and through high school a lot of your confidence and identity is built on superficial stuff like what kind of toys you have, appearance or friend groups.

When you've realized you look a little different from others, and when sometimes kids make fun of you or make comments about the shape of your eyes, you start to want to fit it and become what is "normal."

I grew up wishing I appeared a little less Asian and a little more white.

Even though I was always jealous of the girls with blonde hair and blue eyes, by the time I was in elementary school I had accepted my "biracial-ness" and was a little defensive about it.

In sixth grade, during the presidential physical fitness tests that kids had to take nationwide, we had to bubble in our name and race or sometimes it was bubbled in for us. I have a very distinct memory of double-checking the Scantron with the rest of the class to make sure I had the correct one and seeing "white" filled out for me, in ink, by some official computer somewhere that had determined my race for me.

I remember being mad about this. How dare they not let me choose. You're forbidden to write on them, but I wrote "I AM NOT WHITE" on it. The powers that be — hell, President Bush — should know that I was very unhappy with his decision and should consult me next time.

I met my boyfriend in high school. His name is John Vargas and is also a multiracial millennial.

J.J. and me, 2015.

Vargas was in about second or third grade when he realized he wasn't one race, like everyone else. His dad's side of the family is Mexican, and his mom's side of the family is white and Lebanese.

"Most of my friends were a certain way and I wasn't the same, physically, as them," he says. "And that was always pretty obvious [to me]. And people are like, 'What are you? You're just this white kid.' And it's like, no, not really. But then explaining yourself and your existence to everybody just turns you off."

Vargas is white-presenting, but identifies racially and culturally as Mexican-American but selects two or more races on forms.

When we met, I was tipped off by the name Vargas that he was Hispanic, but visually, he is fair-skinned, with brown hair and red facial hair — pretty white-looking.

"When I first had you on my radar and knew of your existence I honestly thought that you were some kind of Asian," Vargas says. "That was just the vibe that I got and I had a lot of Asian friends so I think that I just had a good feel for the situation and who you were by looking at you."

He remembers asking his friends if they knew me.

"Oh, the Eskimo girl?" was the response.

My identifier was "the Eskimo."

I asked him about my family.

"When I met your parents, I was a thousand times more surprised by your mom than your dad," Vargas says. "And your mom is a very normal-looking white lady and your dad just looks Japanese with glasses and a mustache."

I have a younger sister, Sophie. I think she and I look related.

"I think you and Sophie could have easily been twins," he says.

Me and Sophie in Japan, circa 1997.

Vargas and I have conversations about being multiracial, identity and culture. He struggles with people not recognizing he's Mexican-American and will write him off, or in a work situation will turn down his help, until he starts speaking Spanish.

I had a similar feeling every time I interviewed someone for my book, "70 Years Later: The Japanese-American Internment as Remembered by Those Who Lived Through It."

Calling or emailing old Japanese-Americans to interview them about a common family experience — the internment camps — was incredibly awkward each time showing up not being an Asian person.

I had one man ask me my own last name to make sure I was really Helen Arase.

I got the, "Oh, you must be hapa," from one of the women. Hapa is a Hawaiian term for a person who's partially Asian or Pacific Islander.

My middle name is Masayo, after my paternal grandmother who was in the internment camps. Not being Japanese enough to her peers stung.

I didn't really get over my "not Asian-enough" identity crisis.

Vargas and I talk about being racially and culturally confused quite a bit.

I think that it is important to know your heritage. I feel some sadness that I don't connect as strongly with my mom's heritage. I do think that it's because I just don't know much about it.

I grew up in a very culturally-Japanese household. I feel that I am playing catch up on the Polish side.

He wants any future children to avoid the confusion he feels about his identity. Vargas is anticipating his children to have a lighter complexion.

"If we had kids — my mom is the whitest and your mom is the whitest — people are going to be like, 'Did you guys steal these kids? These white babies?' Like, 'I swear they're mine.'"

Even though Vargas thinks my mom is super white — she has blonde hair, blue eyes and fair skin — he doesn't think I "really" pass for white.

J.J. Vargas talks about why he thinks I don't look white.

I'm not sure that I agree. I think I do pass for white, but also I don't and it just depends on who you ask.

Much of the time I'm perceived to be Hispanic. This is always from strangers. A quick survey of a room reveals basically, I'm ethnically ambiguous.

As I'm writing this I turned around and asked two strangers, "Do I look white?" and after about 10 minutes of discussion and three more people joining the conversation, one of them said, "You could be anything."

I think it is fair to say though that I benefit from white privilege. For the most part, I can live my life without being harassed and probably receive preferable treatment in certain situations.

I have lighter skin than a lot of the world's population, and sometimes that's all you need to benefit.

I have a lifetime of multiracial experiences and awkward encounters about my race.

Vargas and I are reminded every day, at least once a day, of our racial identity. When you don't fit into society's boxes it makes you question yourself more often.